Reading: From the Countryside to the City

From the Countryside to the City

The AGE OF INDUSTRY brought tremendous change to America. Perhaps the single greatest impact of industrialization on the growing nation was urbanization.THOMAS JEFFERSON had once idealized America as a land of small, independent farmers who became educated enough to participate in a republic. That notion was forever a part of history.

As large farms and improved technology displaced the small farmer, a new demand grew for labor in the American economy. Factories spread rapidly across the nation, but they did not spread evenly. Most were concentrated in urban areas, particularly in the Northeast, around the Great Lakes, and on the West Coast. And so the American workforce began to migrate from the countryside to the city.

The speed with which American cities expanded was shocking. About 1/6 of the American population lived in urban areas in 1860. URBAN was defined as population centers consisting of at least 8000 people, only a modest-sized town by modern standards. By 1900 that ratio grew to a third. In just 40 years the urban population increased four times, while the rural population doubled. In 1900, an American was twenty times more likely to move from the farm to the city than vice-versa. The 1920 census declared that for the first time, a majority of Americans lived in the city.

The Best and Worst of American Life

These new cities represented both the best and the worst of American life. Never before in American history had such a large number of Americans lived so close to each other. The ease with which these people could share ideas was never greater. Although these cities produced many products, they were also a huge market. Now, in one small area, citizens could enjoy better and cheaper products.TECHNOLOGY created possibilities as the skyscraper changed the skyline, and electric cars and trolleys decreased commuting time. The light bulb and the telephone transformed every home and business.

There was also a darker side. Beneath the magnificent skylines lay slums of abject poverty. Immigrant neighborhoods struggled to realize the American dream. Overcrowding, disease, and crime plagued many urban communities. Pollution and sewage plagued the new metropolitan centers. Corruption in local leadership often blocked needed improvements.

American values were changing as a result. Urban dwellers sought new faiths to cope with new realities. Relations between men and women, and between adults and children also changed. As the 20th century approached, American ways of life were not necessarily better or worse than before. But they surely were different.

The Glamour of American Cities

They spread like wildfire. For a new factory to beat the competition, it had to be built quickly. Laborers needed fast, cheap housing located close to work. Roads would be hastily built to connect the factory with the market. There was no grand design, and consequently, the new American city spread unpredictably. Urban sprawl had begun. But the growing beast brought benefits that raised the standard of living to new heights.

Going Up

As surely as the city spread outward across the land, it also spread upward toward the sky. Because urban property was in great demand, industrialists needed to maximize small holdings. If additional land was too expensive, why not increase space by building upward? The critical invention leading to this development was of course the fast ELEVATOR, developed by ELISHA OTIS in 1861.

Steel provided a plentiful, durable substance that could sustain tremendous weight. Chicago architect LOUIS SULLIVAN was the foremost designer of the modern SKYSCRAPER. His designing motto was "FORM FOLLOWS FUNCTION." In other words, the purpose of a structure was to be highlighted over its elegance. Beginning with the WAINWRIGHT BUILDING of St. Louis in 1892, Sullivan's steel-framed colossus became the standard for the American skyscraper for the next twenty years. CHICAGO was the perfect site for this new development, because much of the city had been destroyed by a great fire in 1871.

Seeing, Talking, Shopping, and Moving

Few inventions allowed humans to challenge nature more than the light bulb. No longer dependent on the rising and setting of the sun, city dwellers, with their ample supply of ELECTRICITY, could now enjoy a night life that candles simply could not provide. Developed by THOMAS EDISON in 1879, urban areas consumed them at a staggering rate.

ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL added a new dimension to communications with hisTELEPHONE in 1876. The implications for the business world were staggering, as the volume of trade skyrocketed with faster communications. In addition to the telephone, many urban denizens enjoyed electric fans, electric sewing machines, and electric irons by 1900.

Up, up, and away! New York's Woolworth Building took the city to new heights.

The farm could not compete. Most of these new conveniences were confined to the cities because of the difficulties of sending electric power to isolated areas. Indoor plumbing and improved sewage networks added a new dimension of comfort to city life. Department stores such as WOOLWORTH'S, JOHN WANAMKER'S, and MARSHALL FIELD'S provided a large variety of new merchandise of better quality and cheaper than ever before.

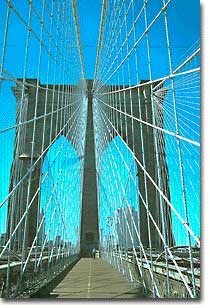

People could reach their destinations faster and faster because of new methods of mass transit. CABLE CARS were operational in cities such as San Francisco and Chicago by the mid-1880s. Boston completed the nation's first underground SUBWAY system in 1897. Middle-class Americans could now afford to live farther from a city's core. Bridges such as the BROOKLYN BRIDGE and improved regional transit lines fueled this trend.

The Underside of Urban Life

Lights, trolleys, skyscrapers, romance, action. These were among the first words to enter the minds of Americans when contemplating the new urban lifestyle. While American cities allowed many middle- and upper-class Americans to live a glamorous lifestyle, this was simply a fantasy to many poorer urban dwellers. Slums, crime, overcrowding, pollution, disease. These words more accurately described daily realities for millions of urban Americans.

Tenements

Much of the urban poor, including a majority of incoming immigrants, lived in tenement housing. If the skyscraper was the jewel of the American city, the tenement was its boil. In 1878, a publication offered $500 to the architect who could provide the best design for MASS-HOUSING. JAMES E. WARE won the contest with his plan for a DUMBBELL TENEMENT. This structure was thinner in the center than on its extremes to allow light to enter the building, no matter how tightly packed the tenements may be. Unfortunately, these "vents" were often filled with garbage. The air that managed to penetrate also allowed a fire to spread from one tenement to the next more easily.

Because of the massive overcrowding, disease was widespread. CHOLERA andYELLOW-FEVER epidemics swept through the slums on a regular basis.TUBERCULOSIS was a huge killer. Infants suffered the most. Almost 25% of babies born in late-19th century cities died before reaching the age of one.

The Stench of Waste, the Stench of Crime

The cities stank. The air stank, the rivers stank, the people stank. Although public sewers were improving, disposing of human waste was increasingly a problem. People used private cesspools, which overflowed with a long, hard rain. Old sewage pipes dumped the waste directly into the rivers or bays. These rivers were often the very same used as water sources.

Trash collection had not yet been systemized. Trash was dumped in the streets or in the waterways. Better sewers, water purification, and trash removal were some of the most pressing problems for city leadership. As the 20th century dawned, many improvements were made, but the cities were far from sanitary.

POVERTY often breeds crime. Desperate people will often resort to theft or violence to put food on the family table when the factory wages would not suffice. Youths who dreaded a life of monotonous factory work and pauperism sometimes roamed the streets in GANGS. VICES such as gambling, prostitution, and alcoholism were widespread. Gambling rendered the hope of getting rich quick. Prostitution provided additional income. Alcoholism furnished a false means of escape. City police forces were often understaffed and underpaid, so those with wealth could buy a better slice of justice.

The glamour of American cities was real indeed. As real was the sheer destitution of its slums. Both worlds — plenty and poverty — existed side by side. As the 20th century began, the plight of the urban poor was heard by more and more reformers, and meaningful change finally arrived.

The Rush of Immigrants

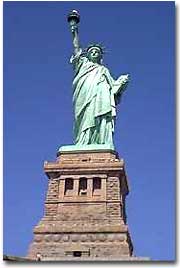

The Statue of Liberty — a gift from France upon the United States' 100th anniversary — welcomed immigrants from around the world to New York City.

IMMIGRATION was nothing new to America. Except for Native Americans, all United States citizens can claim some immigrant experience, whether during prosperity or despair, brought by force or by choice. However, immigration to the United States reached its peak from 1880-1920. The so-called "OLD IMMIGRATION" brought thousands of Irish and German people to the New World.

This time, although those groups would continue to come, even greater ethnic diversity would grace America's populace. Many would come from Southern and Eastern Europe, and some would come from as far away as Asia. New complexions, new languages, and new religions confronted the already diverse American mosaic.

The New Immigrants

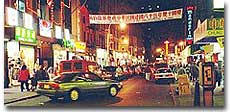

Almost every city in America is home to a Chinatown. This street scene is from New York City's Chinatown — one of the biggest and best-known.

Most immigrant groups that had formerly come to America by choice seemed distinct, but in fact had many similarities. Most had come from Northern and Western Europe. Most had some experience with representative democracy. With the exception of the Irish, most werePROTESTANT. Many were literate, and some possessed a fair degree of wealth.

The new groups arriving by the boatload in the Gilded Age were characterized by few of these traits. Their nationalities included Greek, Italian, Polish, Slovak, Serb, Russian, Croat, and others. Until cut off by federal decree, Japanese and Chinese settlers relocated to the American West Coast. None of these groups were predominantly Protestant.

The vast majority were ROMAN CATHOLIC or EASTERN ORTHODOX. However, due to increased persecution of JEWS in Eastern Europe, many Jewish immigrants sought freedom from torment. Very few newcomers spoke any English, and large numbers were illiterate in their native tongues. None of these groups hailed from democratic regimes. The American form of government was as foreign as its culture.

The new American cities became the destination of many of the most destitute. Once the trend was established, letters from America from friends and family beckoned new immigrants to ethnic enclaves such as CHINATOWN,GREEKTOWN, or LITTLE ITALY. This led to an urban ethnic patchwork, with little integration. The dumbbell tenement and all of its woes became the reality for most newcomers until enough could be saved for an upward move.

Despite the horrors of tenement housing and factory work, many agreed that the wages they could earn and the food they could eat surpassed their former realities. Still, as many as 25% of the European immigrants of this time never intended to become American citizens. These so-called "BIRDS OF PASSAGE" simply earned enough income to send to their families and returned to their former lives.

Resistance to Immigration

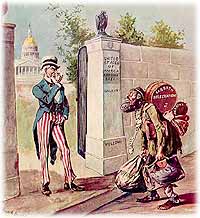

Political cartoons sometimes played on Americans' fears of immigrants. This one, which appeared in a 1896 edition of the Ram's Horn, depicts an immigrant carrying his baggage of poverty, disease, anarchy and sabbath desecration, approaching Uncle Sam.

Not all Americans welcomed the new immigrants with open arms. While factory owners greeted the rush of cheap labor with zeal, laborers often treated their new competition with hostility. Many religious leaders were awestruck at the increase of non-Protestant believers. RACIAL PURISTSfeared the genetic outcome of the eventual pooling of these new bloods.

Gradually, these "NATIVISTS" lobbied successfully to restrict the flow of immigration. In 1882, Congress passed the CHINESE EXCLUSION ACT, barring this ethnic group in its entirety. Twenty-five years later, Japanese immigration was restricted by executive agreement. These two Asian groups were the only ethnicities to be completely excluded from America.

Criminals, contract workers, the mentally ill, anarchists, and alcoholics were among groups to be gradually barred from entry by Congress. In 1917, Congress required the passing of a literacy test to gain admission. Finally, in 1924, the door was shut to millions by placing an absolute cap on new immigrants based on ethnicity. That cap was based on the United States population of 1890 and was therefore designed to favor the previous immigrant groups.

But millions had already come. During the age when the STATUE OF LIBERTYbeckoned the world's "huddled masses yearning to breathe free," American diversity mushroomed. Each brought pieces of an old culture and made contributions to a new one. Although many former Europeans swore to their deaths to maintain their old ways of life, their children did not agree. Most enjoyed a higher standard of living than their parents, learned English easily, and sought American lifestyles. At least to that extent, America was aMELTING POT.

Corruption Runs Wild

Becoming MAYOR of a big city in the Gilded Age was like walking into a cyclone. Demands swirled around city leaders. Better sewers, cleaner water, new bridges, more efficient transit, improved schools, and suitable aid to the sick and needy were some of the more common demands coming from a wide range of interest groups.

To cope with the city's problems, government officials had a limited resources and personnel. Democracy did not flourish in this environment. To bring order out of the chaos of the nation's cities, many political bosses emerged who did not shrink from corrupt deals if they could increase their power bases. The people and institutions the bosses controlled were called the POLITICAL MACHINE.

The Political Machine

Personal politics can at once seem simple and complex. To maintain power, a boss had to keep his constituents happy. Most political bosses appealed to the newest, most desperate part of the growing populace — the immigrants. Occasionally bosses would provide relief kitchens to receive votes. Individuals who were leaders in local neighborhoods were sometimes rewarded city jobs in return for the loyalty of their constituents.

Bosses knew they also had to placate big business, and did so by rewarding them with lucrative contracts for construction of factories or public works. These industries would then pump large sums into keeping the political machine in office. It seemed simple: "You scratch my back and I'll scratch yours." However, bringing diverse interests together in a city as large as New York, Philadelphia, or Chicago required hours of legwork and great political skill.

All the activities mentioned so far seem at least semi-legitimate. The problem was that many political machines broke their own laws to suit their purposes. As contracts were awarded to legal business entities, they were likewise awarded to illegal gambling and prostitution rings. Often profits from these unlawful enterprises lined the pockets of city officials. Public tax money andBRIBES from the business sector increased the bank accounts of these corrupt leaders.

VOTER FRAUD was widespread. Political bosses arranged to have voter lists expanded to include many phony names. In one district a four-year-old child was registered to vote. In another, a dog's name appeared on the polling lists. Members of the machine would "vote early and often," traveling from polling place to polling place to place illegal votes. One district in New York one time reported more votes than it had residents.

Boss Tweed

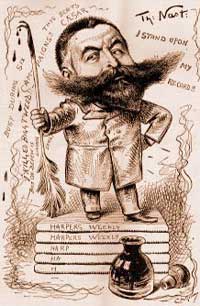

The most notorious political boss of the age was WILLIAM "BOSS" TWEED of New York's TAMMANY HALL. For twelve years, Tweed ruled New York. He gave generously to the poor and authorized the handouts of Christmas turkeys and winter coal to prospective supporters. In the process he fleeced the public out of millions of taxpayer money, which went into the coffers of Tweed and his associates.

Attention was brought to Tweed's corruption by political cartoonist THOMAS NAST. Nast's pictures were worth more than words as many illiterate and semi-literate New Yorkers were exposed to Tweed's graft. A zealous attorney named SAMUEL TILDEN convicted Tweed and his rule came to an end in 1876. Mysteriously, Tweed escaped from prison and traveled to Spain, where he was spotted by someone who recognized his face from Nast's cartoons. He died in prison in 1878.

Religious Revival: The "Social Gospel"

Jane Addams, founder of Hull House in Chicago

The Protestant churches of America feared the worst. Although the population of America was growing by leaps and bounds, there were many empty seats in the pews of urban Protestant churches. Middle-class churchgoers were ever faithful, but large numbers of workers were starting to lose faith in the local church. The old-style heaven and hell sermons just seemed irrelevant to those who toiled long, long hours for small, small wages.

Immigration swelled the ranks of Roman Catholic churches. Eastern Orthodox churches and Jewish synagogues were sprouting up everywhere. At the same time, many cities reported the loss of Protestant congregations. They would have to face this challenge or perish.

Preaching for Politics

Out of this concern grew the social gospel movement. Progressive-minded preachers began to tie the teachings of the church with contemporary problems. Christian virtue, they declared, demanded a redress of poverty and despair on earth.

Many ministers became politically active. WASHINGTON GLADDEN, the most prominent of the social gospel ministers, supported the workers' right to strike in the wake of the Great Upheaval of 1877. Ministers called for an end to child labor, the enactment of temperance laws, and civil service reform.

Liberal churches such as the CONGREGATIONALISTS and the UNITARIANS led the way, but the movement spread to many sects. Middle class women became particularly active in the arena of social reform.

At the same time, a wave of URBAN REVIVALIST PREACHERS swept the nation's cities. The most renowned, DWIGHT LYMAN MOODY, was a shoe salesman who took his fiery oratory on the road. As he traveled from city to city, he attracted crowds large enough to affect local traffic patterns.

The YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION and the YOUNG WOMEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION were formed to address the problems of urban youth. Two new sects formed. MARY BAKER EDDY founded the CHRISTIAN SCIENCE denomination. She tried to reconcile religion and science by preaching that faith was a means to cure evils such as disease. The SALVATION ARMY crossed the Atlantic from England and provided free soup for the hungry.

The Third Great Awakening

The changes were profound. Many historians call this period in the history of American religion the THIRD GREAT AWAKENING. Like the first two awakenings, it was characterized by revival and reform. The temperance movement and the settlement house movement were both affected by church activism. The chief difference between this movement and those of an earlier era was location. These changes in religion transpired because of urban realities, underscoring the social impact of the new American city.

Artistic and Literary Trends

Like the American economy, American art and literature flourished during the Gilded Age. The new millionaires desired greatly to furnish their mansions with beautiful things. Consequently, patronage for the American arts was at a higher level than any previous era. Painters depicted a realistic look at the glories and hardships of this new age. Writers used their pens to illustrate life at its best and its worst. The net result was an AMERICAN RENAISSANCEof arts and letters.

Painting the Gilded Age

Many wealthy Americans yearned to have their image captured for posterity by having their portraits painted. JAMES MCNEILL WHISTLER and JOHN SINGER SARGENT were the most sought after portrait artists of the time. Lured by the idea of working among European masters, both moved to England. Their works endure as among the finest in the genre. Another EXPATRIATE American was the impressionist MARY CASSATT, who moved to Paris to work with the masters MONET and RENOIR. Beyond any artist of the age, she captured women and children at their tender best.

Perhaps the most famous of the postwar American painters was WINSLOW HOMER. Homer gained fame during the Civil War for his realistic illustrations of Union soldiers, which often graced the covers of HARPER'S WEEKLY magazine. After the war he became a serious painter. Life in the American countryside was made real to those who flocked to the cities. His later years were marked with a fascination of the New England coast. Probably no American painter captured the majesty and power of the sea like Homer.

At the same time, Philadelphian THOMAS EAKINS illustrated local behaviors, including a series depicting crew races on the Schuylkill River. His most controversial work, THE GROSS CLINIC, depicted a live medical operation.

Literature

In literature, the dominant figure of the age was MARK TWAIN. Born SAMUEL LANGHORNE CLEMENS, Twain spurned the stodgy New England writing style of the time and brought an added touch of realism by writing in the local color and style of the American Mississippi. HUCKLEBERRY FINN and TOM SAWYEr became genuine American folk heroes to his many readers.

KATE CHOPIN was largely unknown at the time, but her novel THE AWAKENINGbecame a manifesto for future FEMINISTS. STEPHEN CRANE portrayed the horrors of the Civil War with his poignant THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE in 1895.HENRY JAMES struggled with the values of the VICTORIAN AGE by focusing his attention on women. His works DAISY MILLER and PORTRAIT OF A LADY hinted at the tension lying beneath Victorian morality. The horrors of city life were grimly depicted in THEODORE DREISER's SISTER CARRIE, whose representation of a poor working girl offended many a reader.

Postwar poets were prolific. Most notable were WALT WHITMAN for his LEAVES OF GRASS collection and EMILY DICKINSON, whose many poems were published after her death.

In the Home

The visual arts flowered as well. The market for interior design was booming.LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY specialized in stained glass. He combined glorious colors of glass with shells and stones to create beautiful works for fine homes. He was even commissioned to improve the interior of the White House.CANDACE WHEELER pioneered work in tapestry weaving. Wealthy Americans bought these items with a fever, and lavished their homes with marble floors and decorative chandeliers. The American Renaissance was in full swing.