Reading: Western Folkways

Western Folkways

When the Native Americans were placed on reservations, one of the last barriers to western expansion was lifted. The railroad could get people where they wanted to go, and the resources of the West seemed boundless.

How did the typical Westerner make a living? Although migrant settlers had skills too numerous to mention, the most dominant Western industries were mining, ranching, and farming.

"PIKES PEAK OR BUST!" was the motto of many gold-seekers who ventured west during the 1859COLORADO GOLD RUSH. Strikes of gold and silver were found in every western territory.

Eastern industry required lead and other precious metals. The inventions of the telephone, light bulb, and DYNAMO (a massive generator that could pump electricity directly into people's homes) all required copper wiring. New mining techniques presented the possibility for large-scale industry to provide these necessary ores. Life in the western mining towns contributed much to the legendary lore of the American West.

Demand for beef soared after the Civil War. Learning from the Spanish Mexican tradition, cattle ranchers sought their fortunes in Southern Texas. The archetypal American cowboy was needed between 1866 and 1889 to move the steer to market. Life on the open prairies became a reality for thousands of cowhands during the American cattle boom.

By far, the most numerous of western pioneers were the farmers. Seeking a dream of stable existence working a homestead of their own, thousands of migrant families had their dreams dashed by the harsh realities of western life. Nature, isolation, politics, and economics all seemed to work against the hopeful farmer.

Soon farm issues spilled into politics as new groups and political parties formed demanding a better deal for rural America. The nation voted zealously and in larger numbers than ever before when the 1896 election proposed to shift the balance of power in America back to its agricultural roots. But it was not to be. America's future seemed to lie in the direction of the industrial Northeast. But as the 19th century expired, millions of westerners struggled to keep the bucolic past hitched to the present.

The Mining Boom

Bonanza

BONANZA! That was the exclamation when a large vein of valuable ore was discovered. Thousands of optimistic Americans and even a few foreigners dreamed of finding a bonanza and retiring at a very young age.

Ten years after the 1849 CALIFORNIA GOLD RUSH, new deposits were gradually found throughout the West. Colorado yielded gold and silver at PIKES PEAK in 1859 and LEADVILLE IN 1873.NEVADA claimed COMSTOCK LODE, the largest of American silver strikes.

From COEUR D'ALENE in Idaho to TOMBSTONE in Arizona, BOOM TOWNS flowered across the American West. They produced not only gold and silver, but zinc, copper, and lead, all essential for the eastern Industrial Revolution. Soon the West was filled with ne'er-do-wells hoping to strike it rich.

Prospecting

Few were so lucky. The chances of an individual prospector finding a valuable lode were slim indeed. The gold-seeker often worked in a stream bed. A tin pan was filled with sediment and water. After shaking, the heavier gold nuggets would sink to the bottom. Rarely was anything found of substantial size.

Prospectors like Potato Creek Johnny looked to strike it rich with a bonanza. Johnny gained fame when he found one of the largest nuggets of gold on record.

Once the loose chunks of gold were removed from the surface, large machinery was required to dig into the earth and to split the quartz where the elusive gold was often hidden. This was too large of an operation for an individual prospector. Eastern investors conducted these ventures and often profited handsomely. The best case scenario for the prospector was to locate a large deposit and sell the claim. Those who were not as lucky often eventually went to work in the mines of the Eastern financiers.

WESTERN MINING wrought havoc on the local environment. Rock dust from drilling was often dumped into river beds, forming silt deposits downstream that flooded towns and farmlands. Miners and farmers were often at loggerheads over the effects of one enterprise on the other. Poisonous underground gases, mostly containing sulfur, were released into the atmosphere. Removing gold from quartz required mercury, the excess of which polluted local streams and rivers. Strip mining caused erosion and further desertification. Little was done to regulate the mining industry until the turn of the 20th century.

Life in a Mining Town

Each mining bonanza required a town. Many towns had as high as a 9-to-1 male-to-female ratio. The ethnic diversity was great. Mexican immigrants were common. Native Americans avoided the mining industry, but mestizos, the offspring of Mexican and Native American parents, often participated. Many African Americans aspired to the same get-rich-quick idea as whites. Until excluded by federal law in 1882, Chinese Americans were numerous in mining towns.

The ethnic patchwork was intricate, but the socio-economic ladder was clearly defined. Whites owned and managed all of the mines. Poor whites, Mexicans and Chinese Americans worked the mine shafts. A few African Americans joined them, but many worked in the service sector as cooks or artisans.

It is these mining towns that often conjure images of the mythical American Wild West. Most did have a saloon (or several) with swinging doors and a player piano. But miners and prospectors worked all day; few had the luxury of spending it at the bar. By nighttime, most were too tired to carouse. Weekends might bring folks out to the saloon for gambling or drinking, to engage in the occasional bar fight, or even to hire a prostitute.

Law enforcement was crude. Many towns could not afford a sheriff, so vigilante justice prevailed. Occasionally a posse, or hunting party, would be raised to capture a particularly nettlesome miscreant.

The Ways of the Cowboy

Mining was not the only bonanza to be found in the West. Millions could be made in the CATTLE INDUSTRY. A calf bought for $5 in Southern Texas might sell for $60 in Chicago. The problem was, of course, getting the cattle to market.

In 1867, JOSEPH MCCOY tracked a path known as the CHISHOLM TRAIL from Texas to Abilene, Kansas. The Texas cowboys drove the cattle the entire distance — 1500 miles. Along the way, the cattle enjoyed all the grass they wanted, at no cost to the RANCHERS. At Abilene and other railhead towns such as Dodge City and Ellsworth, the cattle would be sold and the cowboys would return to Texas.

No vision of the American West is complete without the cowboy. The imagery is quintessentially American, but many myths cloud the truth about what life was like on the long drive.

Myth vs. Reality

Americans did not invent cattle raising. This tradition was learned from thevaquero, a Mexican cowboy. The vacqueros taught the tricks of the trade to the Texans, who realized the potential for great profits.

The typical COWBOY wore a hat with a wide brim to provide protection from the unforgiving sunlight. Cattle kicked up clouds of dust on the drive, so the cowboy donned a bandanna over the lower half of his face. CHAPS, or leggings, and high boots were worn as protection from briars and cactus needles.

Contrary to legend, the typical cowboy was not a skilled marksman. The lariat, not the gun, was how the cattle drover showed his mastery. About a quarter of all cowboys were African Americans, and even more were at least partially Mexican. To avoid additional strain on the horses, cowboys were usually smaller than according to legend.

The lone cowboy is an American myth. Cattle were always driven by a group of DROVERS. The cattle were branded so the owner could distinguish his STEERfrom the rest. Several times per DRIVE, cowboys conducted a roundup where the cattle would be sorted and counted again.

Work was very difficult. The workdays lasted fifteen hours, much of which was spent in the saddle. Occasionally, shots were fired by hostile Indians or farmers. Cattle RUSTLERS sometimes stole their steers.

One of the greatest fears was the STAMPEDE, which could result in lost or dead cattle or cowboys. One method of containing a stampede was to get the cattle to run in a circle, where the steer would eventually tire.

Upon reaching Abilene, the cattle were sold. Then it was time to let loose. Abilene had twenty-five saloons open all hours to service incoming riders of the long drive.

Twilight of the Cowboy

The heyday of the long drive was short. By the early 1870s, rail lines reached Texas so the cattle could be shipped directly to the slaughterhouses. Ranchers then began to allow cattle to graze on the open range near rail heads. But even this did not last. The invention of BARBED WIRE by JOSEPH GLIDDEN ruined the OPEN RANGE. Now farmers could cheaply mark their territory to keep the unwanted steers off their lands. Overproduction caused prices to fall, leading many ranchers out of business.

Finally, the winter of 1886-87 was one of the worst in American history. Cattle died by the thousands as temperatures reached fifty below zero in some parts of the West. The era of the open range was over.

Life on the Farm

This little house on the prairie is constructed of sod walls and a dirt roof. It is one of the few pioneer dwellings still standing in the Badlands today.

A homestead at last! Many eastern families who longed for the opportunity to own and farm a plot of land of their own were able to realize their dreams when Congress passed the HOMESTEAD ACT in 1862. That landmark piece of legislation provided 160 acres free to any family who lived on the land for five years and made improvements. The same amount could be obtained instantly for the paltry sum of $1.25 per acre.

Combined with the completed transcontinental railroad, it was now possible for an easterner yearning for the open space of the West to make it happen. Unfortunately, the lives they found were fraught with hardship.

Money Problems

There were tremendous economic difficulties associated with Western farm life. First and foremost was overproduction. Because the amount of land under cultivation increased dramatically and new farming techniques produced greater and greater yields, the food market became so flooded with goods that prices fell sharply. While this might be great for the consumer, the farmer had to grow a tremendous amount of food to recoup enough profits to survive the winter.

New machinery and fertilizer was needed to farm on a large scale. Often farmers borrowed money to purchase this equipment, leaving themselves hopelessly in debt when the harvest came. The high tariff forced them to pay higher prices for household goods for their families, while the goods they themselves sold were unprotected.

The railroads also fleeced the small farmer. Farmers were often charged higher rates to ship their goods a short distance than a manufacturer would pay to transport wares a great distance.

A Harsh and Isolating Environment

The woes faced by farmers transcended economics. Nature was unkind in many parts of the Great Plains. Blistering summers and cruel winters were commonplace. Frequent drought spells made farming even more difficult. Insect blights raged through some regions, eating further into the farmers' profits.

Farmers lacked political power. Washington was a long way from the Great Plains, and politicians seemed to turn deaf ears to the farmers' cries. Social problems were also prevalent. With each neighbor on 160-acre plots of land, communication was difficult and loneliness was widespread.

Farm life proved monotonous compared with the bustling cities of the East. Although rural families were now able to purchase MAIL-ORDER PRODUCTSthrough catalogs such as SEARS AND ROEBUCK'S and MONTGOMERY WARD, there was simply no comparison with what the Eastern market could provide.

These conditions could not last. Out of this social and economic unrest, farmers began to organize and make demands that would rock the Eastern establishment.

The Growth of Populism

The Grange borrowed heavily from the Freemasons, employing complex rituals and regalia.

Organization was inevitable. Like the oppressed laboring classes of the East, it was only a matter of time before Western farmers would attempt to use their numbers to effect positive change.

Farmers Organize

In 1867, the first such national organization was formed. Led by OLIVER KELLEY, thePATRONS OF HUSBANDRY, also known as theGRANGE, organized to address the social isolation of farm life. Like other SECRET SOCIETIES, such as the MASONS,GRANGERS had local chapters with secret passwords and rituals.

The local Grange sponsored dances and gatherings to attack the doldrums of daily life. It was only natural that politics and economics were discussed in these settings, and the Grangers soon realized that their individual problems were common.

Identifying the railroads as the chief villains, Grangers lobbied state legislatures for regulation of the industry. By 1874, several states passed theGRANGER LAWS, establishing maximum shipping rates. Grangers also pooled their resources to buy grain elevators of their own so that members could enjoy a break on grain storage.

Morgan dollar (1878-1891)

FARMERS' ALLIANCES went one step further. Beginning in 1889, NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN FARMERS' ALLIANCESchampioned the same issues as the Grangers, but also entered the political arena. Members of these alliances won seats in state legislatures across the Great Plains to strengthen the agrarian voice in politics.

Creating Inflation

What did all the farmers seem to have in common? The answer was simple: debt. Looking for solutions to this condition, farmers began to attack the nation's monetary system. As of 1873, Congress declared that all federal money must be backed by gold. This limited the nation's money supply and benefited the wealthy.

The farmers wanted to create INFLATION. Inflation actually helps debtors. If a farmer owes $3,000 and can earn $1 for every bushel of wheat sold at harvest, he needs to sell 3,000 bushels to pay off the debt. If inflation could push the price of a bushel of wheat up to $3, he needs to sell only 1,000 bushels. The economics are simple.

To create inflation, farmers suggested that the money supply be expanded to include dollars not backed by gold. The first strategy farmers attempted was to encourage Congress to print GREENBACK DOLLARS like the ones issued during the Civil War. Since the greenbacks were not backed by gold, more dollars could be printed, creating an inflationary effect.

The GREENBACK PARTY and the GREENBACK-LABOR PARTY each ran candidates for President in 1876, 1880, and 1884 under this platform. No candidate was able to muster national support for the idea, and soon farmers chose another strategy.

Inflation could also be created by printing money that was backed by silver as well as gold. This idea was more popular because people were more confident in their money if they knew it was backed by something of value. Also, America had a tradition of coining SILVER MONEY until 1873.

Many believe that The Wizard of Oz was written as an allegory of the age of Populism.

Birth of the Populists

Out of the ashes of the Greenback-Labor Party grew the POPULIST PARTY. In addition to demanding the free coinage of silver, thePOPULISTS called for a host of other reforms. They demanded a graduated income tax, whereby individuals earning a higher income paid a higher percentage in taxes.

They wanted political reforms as well. At this point, United States Senators were still not elected by the people directly; they were instead chosen by state legislatures. The Populists demanded a constitutional amendment allowing for the direct election of Senators.

They demanded democratic reforms such as the initiative, where citizens could directly introduce debate on a topic in the legislatures. The referendum would allow citizens — rather than their representatives — to vote a bill. Recall would allow the people to end an elected official's term before it expired. They also called for the secret ballot and a one-term limit for the President.

In 1892, the Populists ran JAMES WEAVER for President on this ambitious platform. He polled over a million popular votes and 22 electoral votes. Although he came far short of victory, Populist ideas were now being discussed at the national level. When the Panic of 1893 hit the following year, an increased number of unemployed and dispossessed Americans gave momentum to the Populist movement. A great showdown was in place for 1896.

The Election of 1896

Everything seemed to be falling into place for the Populists. James Weaver made an impressive showing in 1892, and now Populist ideas were being discussed across the nation. The Panic of 1893 was the worst financial crisis to date in American history. As the soup lines grew larger, so did voters' anger at the present system.

When JACOB S. COXEY of Ohio marched his 200 supporters into the nation's capital to demand reforms in the spring of 1894, many thought a revolution was brewing. The climate seemed to ache for change. All that the Populists needed was a winning Presidential candidate in 1896.

The Boy Orator

Ironically, the person who defended the Populist platform that year came from the Democratic Party. WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN was the unlikely candidate. An attorney from Lincoln, Nebraska, Bryan's speaking skills were among the best of his generation. Known as the "GREAT COMMONER," Bryan quickly developed a reputation as defender of the farmer.

When Populist ideas began to spread, Democratic voters of the South and West gave enthusiastic endorsement. At the Chicago Democratic convention in 1896, Bryan delivered a speech that made his career. Demanding the free coinage of silver, Bryan shouted, "You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!" Thousands of delegates roared their approval, and at the age of thirty-six, the "BOY ORATOR" received the Democratic nomination.

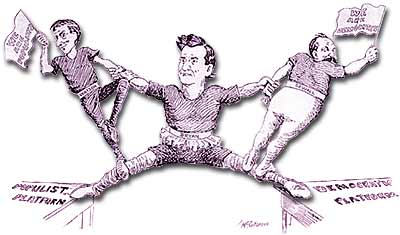

Faced with a difficult choice between surrendering their identity and hurting their own cause, the Populist Party also nominated Bryan as their candidate.

The Stay-at-Home Candidate

William McKinley stayed out of the public eye in 1896, leaving the campaigning to party hacks and fancy posters like this one.

The Republican competitor wasWILLIAM MCKINLEY, the governor of Ohio. He had the support of the moneyed eastern establishment. Behind the scenes, a wealthy Cleveland industrialist namedMARC HANNA was determined to see McKinley elected. He, like many of his class, believed that the free coinage of silver would bring financial ruin to America.

Using his vast wealth and power, Hanna directed a campaign based on fear of a Bryan victory. McKinley campaigned from his home, leaving the politicking for the party hacks. Bryan revolutionized campaign politics by launching a nationwide WHISTLE-STOPeffort, making twenty to thirty speeches per day.

When the results were finally tallied, McKinley had beaten Bryan by an electoral vote margin of 271 to 176.

Understanding 1896

Many factors led to Bryan's defeat. He was unable to win a single state in the populous Northeast. Laborers feared the free silver idea as much as their bosses. While inflation would help the debt-ridden, mortgage-paying farmers, it could hurt the wage-earning, rent-paying factory workers. In a sense, the election came down to city versus country. By 1896, the urban forces won. Bryan's campaign marked the last time a major party attempted to win the White House by exclusively courting the rural vote.

The economy of 1896 was also on the upswing. Had the election occurred in the heart of the Panic of 1893, the results may have differed. Farm prices were rising in 1896, albeit slowly. The Populist Party fell apart with Bryan's loss. Although they continued to nominate candidates, most of their membership had reverted to the major parties.

The ideas, however, did endure. Although the free silver issue died, the graduated income tax, direct election of senators, initiative, referendum, recall, and the secret ballot were all later enacted. These issues were kept alive by the next standard bearers of reform — the PROGRESSIVES.

When the bonanza was at its zenith, the town prospered. But eventually the mines were exhausted or proved fruitless. Slowly its inhabitants would leave, leaving behind nothing but a ghost town.