Reading: Progressivism Sweeps the Nation

Progressivism Sweeps the Nation

Student in the Electrical Division at Tuskegee Institute

Conservatives beware! Whether they liked it or not, the turn of the 20th century was an age of reform. Urban reformers and Populists had already done much to raise attention to the nation's most pressing problems.

America in 1900 looked nothing like America in 1850, yet those in power seemed to be applying the same old strategies to complex new problems. The Populists had tried to effect change by capturing the government. The Progressives would succeed where the Populists had failed.

The Progressives were urban, Northeast, educated, middle-class, Protestant reform-minded men and women. There was no official PROGRESSIVE PARTY until 1912, but progressivism had already swept the nation.

It was more of a movement than a political party, and there were adherents to the philosophy in each major party. There were three PROGRESSIVE PRESIDENTS — Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. Roosevelt and Taft were Republicans and Wilson was a Democrat. What united the movement was a belief that the laissez faire, Social Darwinist outlook of the Gilded Age was morally and intellectually wrong. Progressives believed that people and government had the power to correct abuses produced by nature and the free market.

The results were astonishing. Seemingly every aspect of society was touched by progressive reform. Worker and consumer issues were addressed, conservation of natural resources was initiated, and the plight of the urban poor was confronted. National political movements such as temperance and women's suffrage found allies in the progressive movement. The era produced a host of national and state regulations, plus four amendments to the Constitution.

When the United States became involved in the First World War, attention was diverted from domestic issues and progressivism went into decline. While unable to solve the problems of every American, the PROGRESSIVE ERA set the stage for the 20th century trend of an activist government trying to assist its people.

Roots of the Movement

The first page to Edward Bellamy's "Looking Backward" in which people from the year 2,000 look back to 1887

The single greatest factor that fueled the progressive movement in America was urbanization. For years, educated, middle-class women had begun the work of reform in the nation's cities.

Jane Addams was a progressive before the movement had such a name. The settlement house movement embodied the very ideals of progressivism. Temperance was a progressive movement in its philosophy of improving family life. "SOCIAL GOSPEL" preachers had already begun to address the needs of city dwellers.

Progressive Writing

Urban intellectuals had ready stirred consciences with their controversial treatises. HENRY GEORGE attracted many followers by blaming inequalities in wealth on land ownership. In his 1879 work, PROGRESS AND POVERTY, he suggested that profits made from land sales be taxed at a rate of 100 percent.

EDWARD BELLAMY peered into the future in his 1888 novel, LOOKING BACKWARD. The hero of the story wakes up in the year 2000 and looks back to see that all the hardships of the Gilded Age have withered away thanks to an activist, utopian socialist government.

In THE THEORY OF THE LEISURE CLASS (1899), THORSTEIN VEBLEN cited countless cases of "CONSPICUOUS CONSUMPTION." Wealthy families spent their riches on acquiring European works of art or fountains that flowed with champagne. Surely, he argued, those resources could be put to better use.

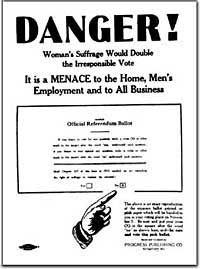

Women's Suffrage Poster

Pragmatic Solutions

Underlying this new era of reform was a fundamental shift in philosophy away from Social Darwinism. Why accept hardship and suffering as simply the result of natural selection? Humans can and have adapted their physical environments to suit their purposes. Individuals need not accept injustices as the "law of nature" if they can think of a better way.

Philosopher WILLIAM JAMES called this new way of thinking, "PRAGMATISM." His followers came to believe that an activist government could be the agent of the public to pursue the betterment of social ills.

The most prolific disciple of James was JOHN DEWEY. Dewey applied pragmatic thinking to education. Rather than having students memorize facts or formulas, Dewey proposed "LEARNING BY DOING." The progressive education movement begun by Dewey dominated educational debate the entire 20th century.

The Populist Influence

The Populist movement also influenced progressivism. While rejecting the call for free silver, the progressives embraced the political reforms of SECRET BALLOT, INITIATIVE, REFERENDUM, and RECALL. Most of these reforms were on the state level. Under the governorship of ROBERT LAFOLLETTE, Wisconsin became a laboratory for many of these political reforms.

The Populist ideas of an income tax and direct election of senators became the SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH AMENDMENTS to the United States Constitution under progressive direction.

Reforms went further by trying to root out urban corruption by introducing new models of city government. The city commission and the city manager systems removed important decision making from politicians and placed it in the hands of skilled technicians. The labor movement contributed the calls for workers' compensation and child labor regulation.

Progressivism came from so many sources from every region of America. The national frame of mind was fixed. Reform would occur. It was only a matter of how much and what type.

Muckrakers

Upton Sinclair published The Junglein 1905 to expose labor abuses in the meat packing industry. But it was food, not labor, that most concerned the public. Sinclair's horrific descriptions of the industry led to the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act, not to labor legislation.

The pen is sometimes mightier than the sword.

It may be a cliché, but it was all too true for journalists at the turn of the century. The print revolution enabled publications to increase their subscriptions dramatically. What appeared in print was now more powerful than ever. Writing to Congress in hopes of correcting abuses was slow and often produced zero results. Publishing a series of articles had a much more immediate impact. Collectively calledMUCKRAKERS, a brave cadre of reporters exposed injustices so grave they made the blood of the average American run cold.

Steffens Takes on Corruption

The first to strike was LINCOLN STEFFENS. In 1902, he published an article inMCCLURE'S magazine called "TWEED DAYS IN ST. LOUIS." Steffens exposed how city officials worked in league with big business to maintain power while corrupting the public treasury.

More and more articles followed, and soon Steffens published the collection as a book entitled THE SHAME OF THE CITIES. Soon public outcry demanded reform of city government and gave strength to the progressive ideas of a city commission or city manager system.

Tarbell vs. Standard Oil

IDA TARBELL struck next. One month after Lincoln Steffens launched his assault on urban politics, Tarbell began her McClure's series entitled "HISTORY OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY." She outlined and documented the cutthroat business practices behind John Rockefeller's meteoric rise. Tarbell's motives may also have been personal: her own father had been driven out of business by Rockefeller.

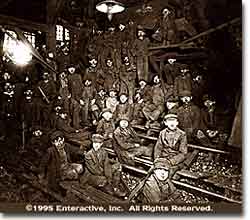

John Spargo's 1906 The Bitter Cry of the Children exposed hardships suffered by child laborers, such as these coal miners. "From the cramped position [the boys] have to assume," wrote Spargo, "most of them become more or less deformed and bent-backed like old men ... "

Once other publications saw how profitable these exposés had been, they courted muckrakers of their own. In 1905, THOMAS LAWSON brought the inner workings of the stock market to light in FRENZIED FINANCE. JOHN SPARGO unearthed the horrors of child labor in THE BITTER CRY OF THE CHILDREN in 1906. That same year, DAVID PHILLIPS linked 75 senators to big business interests in THE TREASON OF THE SENATE. In 1907, WILLIAM HARD went public with industrial accidents in the steel industry in the blisteringMAKING STEEL AND KILLING MEN.RAY STANNARD BAKER revealed the oppression of Southern blacks in FOLLOWING THE COLOR LINE in 1908.

The Meatpacking Jungle

Perhaps no muckraker caused as great a stir as UPTON SINCLAIR. An avowed Socialist, Sinclair hoped to illustrate the horrible effects of capitalism on workers in the Chicago meatpacking industry. His bone-chilling account, THE JUNGLE, detailed workers sacrificing their fingers and nails by working with acid, losing limbs, catching diseases, and toiling long hours in cold, cramped conditions. He hoped the public outcry would be so fierce that reforms would soon follow.

The clamor that rang throughout America was not, however, a response to the workers' plight. Sinclair also uncovered the contents of the products being sold to the general public. Spoiled meat was covered with chemicals to hide the smell. Skin, hair, stomach, ears, and nose were ground up and packaged as head cheese. Rats climbed over warehouse meat, leaving piles of excrement behind.

Sinclair said that he aimed for America's heart and instead hit its stomach. Even President Roosevelt, who coined the derisive term "muckraker," was propelled to act. Within months, Congress passed the PURE FOOD AND DRUG ACT and the MEAT INSPECTION ACT to curb these sickening abuses.

Women's Suffrage at Last

After the SENECA FALLS CONVENTION of 1848 demanded WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE for the first time, America became distracted by the coming Civil War. The issue of the vote resurfaced during Reconstruction.

The FIFTEENTH AMENDMENTto the Constitution proposed granting the right to vote to African American males. Many female suffragists at the time were outraged. They simply could not believe that those who suffered 350 years of bondage would be enfranchised before America's women.

A Movement Divided

Activists such as FREDERICK DOUGLASS, LUCY STONE, and HENRY BLACKWELLargued that the 1860s was the time for the black male. Linking black suffrage with female suffrage would surely accomplish neither. SUSAN B. ANTHONY,ELIZABETH CADY STANTON, and SOJOURNER TRUTH disagreed. They would accept nothing less than immediate federal action supporting the vote for women.

Voting rights were guaranteed for women in the U.S. in 1920 with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment. But women's suffrage campaigns have been fought around the world. What nations were ahead of the U.S. in voting equality and what nations still ban women from casting their votes?

Stone and Blackwell formed the AMERICAN WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION and believed that pressuring state governments was the most effective route. Anthony and Stanton formed the NATIONAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION and pressed for a constitutional amendment. This split occurred in 1869 and weakened the suffrage movement for the next two decades.

Anthony and Stanton engaged in high-profile, headline-grabbing tactics. In 1872, they endorsedVICTORIA WOODHULL, the FREE LOVE CANDIDATE, for President. The NWSA was known to show up to the polls on election day to force officials to turn them away. They set up mock ballot boxes near the election sites so women could "vote" in protest. They continued to accept no compromise on a national amendment eliminating the gender requirement.

The AWSA chose a much more understated path. Stone and Blackwell actively lobbied state governments. WYOMING became the first state to grant full women's suffrage in 1869, and UTAH followed suit the following year. But then it stopped. No other states granted full suffrage until the 1890s.

|

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman? – Sojourner Truth. "Ain't I A Woman?" Delivered at Akron Ohio Women's Covention (1851) |

||

The NAWSA to the Rescue

After Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell passed away, their daughter, ALICE STONE BLACKWELL saw the need for a unified front. She approached the aging leadership of the NWSA, and in 1890, the two splinter groups formed theNATIONAL AMERICAN WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION (NAWSA), with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony taking turns at the presidency.

Although the movement still had internal divisions, the mood of progressive reform breathed new life into its rank and file. Although Stanton and Anthony died before ever having accomplished their goal, the stage was set for a new generation to carry the torch.

The fight to victory was conducted by CARRIE CHAPMAN CATT. By 1910, most states west of Mississippi had granted full suffrage rights to women. States of the Midwest at least permitted women to vote in Presidential elections. But the Northeast and the South were steadfast in opposition. Catt knew that to ratify a national amendment, NAWSA would have to win a state in each of these key regions. Once cracks were made, the dam would surely burst.

Amid the backdrop of the United States entry into World War I, success finally came. In 1917, New York and Arkansas permitted women to vote, and momentum shifted toward suffrage. NAWSA supported the war effort throughout the ratification process, and the prominent positions women held no doubt resulted in increased support.

On August 26, 1920, the NINETEENTH AMENDMENT became the supreme law of the land, and the long struggle for voting rights was over.

Booker T. Washington

At the dawn of the 20th century, nine out of ten African Americans lived in the South. Jim Crow laws of segregation ruled the land. The Supreme Court upheld the power of the Southern states to create two "SEPARATE BUT EQUAL" societies with its 1896 PLESSY V. FERGUSON opinion. It would be for a later Supreme Court to judge that they fell short of the "equal" requirement.

Although empowered to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment, POLL TAXES,LITERACY TESTS, and outright violence and intimidation reduced the voting black population to almost zero. Economically, African Americans were primarily poor sharecroppers trapped in an endless cycle of debt. Socially, few whites had come to accept blacks as equals. While progressive reformers ambitiously attacked injustices, it would take great work and great people before change was felt. One man who took up the challenge was BOOKER T. WASHINGTON.

Founding Tuskegee Institute

Born into slavery in 1856, Washington had experienced racism his entire life. When emancipated after the Civil War, he became one of the few African Americans to complete school, whereupon he became a teacher.

Believing in practical education, Washington established a TUSKEGEE INSTITUTEin Alabama at the age of twenty-five. Washington believed that Southern racism was so entrenched that to demand immediate social equality would be unproductive. His school aimed to train African Americans in the skills that would help the most.

Tuskegee Institute became a center for agricultural research. The most famous product of Tuskegee was GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER. Carver concluded that much more productive use could be made of agricultural lands by diversifying crops. He discovered hundreds of new uses for sweet potatoes, pecans, and peanuts. Peanut butter was one such example. Washington saw a future in this new type of agriculture as a means of raising the economic status of African Americans.

The Atlanta "Compromise"

In 1895, Washington delivered a speech at the ATLANTA EXPOSITION. He declared that African Americans should focus on VOCATIONAL EDUCATION. Learning Latin and Greek served no purpose in the day-to-day realities of Southern life.

African Americans should abandon their short-term hopes of social and political equality. Washington argued that when whites saw African Americans contributing as productive members of society, equality would naturally follow.

For those dreaming of a black utopia of freedom, Washington declared, "Cast down your bucket where you are." Many whites approved of this moderate stance, while African Americans were split. Critics called his speech the Atlanta Compromise and accused Washington of coddling Southern racism.

Still, by 1900, Washington was seen as the leader of the African American community. In 1901, he published his autobiography, UP FROM SLAVERY. He was a self-made man and a role model to thousands. In 1906, he was summoned to the White House by President Theodore Roosevelt. This marked the first time in American history that an African American leader received such a prestigious invitation.

Despite his accomplishments, he was challenged within the black community until his death in 1915. His most outspoken critic was W. E. B. DuBois.

W. E. B. DuBois

Founding members of the Niagara Movement, formed to assert full rights and opportunity to African Americans. "We want full manhood suffrage and we want it now.... We are men! We want to be treated as men. And we shall win." W.E.B. DuBois is on the second row, second from the right.

WILLIAM EDWARD BURGHARDT DUBOIS was very angry with Booker T. Washington. Although he admired Washington's intellect and accomplishments, he strongly opposed the position set forth by Washington in his Atlanta Exposition Address. He saw little future in agriculture as the nation rapidly industrialized. DuBois felt that renouncing the goal of complete integration and social equality, even in the short run, was counterproductive and exactly the opposite strategy from what best suited African Americans.

Early Life and Core Beliefs

The childhood of W. E. B. DuBois could not have been more different from that of Booker T. Washington. He was born in Massachusetts in 1868 as a free black. DuBois attended FISK UNIVERSITY and later became the first African American to receive a Ph. D. from Harvard. He secured a teaching job at Atlanta University, where he believed he learned a great deal about the African American experience in the South.

DuBois was a staunch proponent of a classical education and condemned Washington's suggestion that blacks focus only on vocational skills. Without an educated class of leadership, whatever gains were made by blacks could be stripped away by legal loopholes. He believed that every class of people in history had a "TALENTED TENTH." The downtrodden masses would rely on their guidance to improve their status in society.

Political and social equality must come first before blacks could hope to have their fair share of the economic pie. He vociferously attacked the Jim Crow laws and practices that inhibited black suffrage. In 1903, he published THE SOULS OF BLACK FOLK, a series of essays assailing Washington's strategy of accommodation.

The Niagra Movement and the NAACP

In 1905, DuBois met with a group of 30 men at Niagara Falls, Canada. They drafted a series of demands essentially calling for an immediate end to all forms of discrimination. The NIAGARA MOVEMENT was denounced as radical by most whites at the time. Educated African Americans, however, supported the resolutions.

Four years later, members of the Niagara Movement formed the NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP). This organization sought to fight for equality on the national front. It also intended to improve the self-image of African Americans. After centuries of slavery and decades of second-class status, DuBois and others believed that many African Americans had come to accept their position in American society.

DuBois became the editor of the organization's periodical called THE CRISIS, a job he performed for 20 years. The Crisis contained the expected political essays, but also poems and stories glorifying African American culture and accomplishments. Later, DuBois was invited to attend the organizational meeting for the United Nations in 1946.

As time passed, DuBois began to lose hope that African Americans would ever see full equality in the United States. In 1961, he moved to Ghana. He died at the age of 96 just before Martin Luther King Jr. led the historical civil rights march on Washington.