Reading: Progressives in the White House

Progressives in the White House

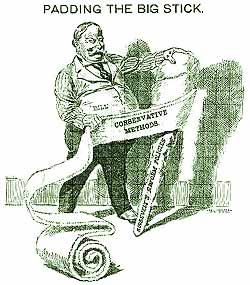

Hiding Teddy

THEODORE ROOSEVELT was never intended to be President. He was seen as a reckless cowboy by many in the Republican Party leadership. As his popularity soared, he became more and more of a threat. His success with the Rough Riders in Cuba made him a war hero in the eyes of many Americans. Riding this wave, he was elected as governor of New York.

During the campaign of 1900, it was decided that nominating Roosevelt for the Vice-Presidency would serve two purposes. First, his popularity would surely help President McKinley's reelection bid. Second, moving him to the Vice-Presidency might decrease his power.

Vice-Presidents had gone on to the White House only if the sitting President died in office. The last Vice-President elected in his own right had been Martin Van Buren in 1837. Many believed Roosevelt could do less harm as Vice-President than as governor of New York.

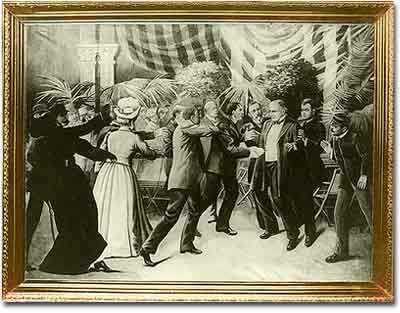

McKinley and Roosevelt won the election, and all was proceeding according to plan until an assassin's bullet ended McKinley's life in September 1901.

The Bully Pulpit

Roosevelt did not wait long to act. Before long he lashed out against the trusts and sided with American labor. The Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act protected consumers. Steps were taken to protect America's wilderness lands that went beyond any previous President.

The worst fears of conservatives were realized as Roosevelt used the White House as a "BULLY PULPIT" to promote an active government that protected the interests of the people over big business. The Progressive movement finally had an ally in the White House.

The Progressive lock on the Presidency did not end with Theodore Roosevelt. His popularity secured the election in 1908 of his hand-picked successor, William Howard Taft. Although Taft continued busting America's trusts, his inability to control the conservative wing of the party led to a Republican versus Republican war.

A Progressive Democrat

Teddy Roosevelt challenged Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912, splitting the party wide open. Although the Republicans lost the election, it was not necessarily a loss for Progressives. The winning Democrat, Woodrow Wilson, embraced much of the Progressive agenda himself.

Before his two terms came to a close, the federal government passed legislation further restricting trusts, banning child labor, and requiring worker compensation. The Progressive causes of temperance and women's suffrage were embedded into the Constitution.

Between 1901 and 1921, the Presidents were more active and powerful than any since the days of Abraham Lincoln.

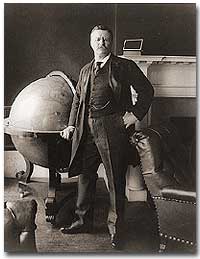

Teddy Roosevelt: The Rough Rider in the White House

Teddy Roosevelt was a fearless friend of nature. Mark Twain called him " the Tom Sawyer of the political world of the twentieth century."

There had never been a President like him. He was only forty-two years old when his predecessor William McKinley was assassinated, the youngest age ever for the chief executive.

He was graduated with the highest honors from Harvard, wrote 23 books, and was considered the world's foremost authority on North American wildlife. He was a prizefighting championship finalist, leader of the Rough Riders, a cowboy, a socialite, a police commissioner, a governor, and a Vice-President.

All this was accomplished before he entered the White House. His energy was contagious, and the whole country was electrified by their new leader.

Early Obstacles

Roosevelt was born in 1858 to a wealthy New York banker and the daughter of a prosperous Georgia planter. He was anything but the model physical specimen. His eyesight was poor. He wore thick glasses his entire life. As a child he was small and weak. He suffered from acute asthma, which contributed to his frailty.

Taking his father's advice, he dedicated himself to physical fitness, without which he believed there could be no mental fitness. His hard work paid off, and as he entered Harvard with a muscular frame, his condition bothered him less and less.

Soon he met ALICE HATHAWAY LEE. Although he believed her to be the most unobtainable woman around, he was determined to marry her. Again, he was successful, but his life with Alice was short-lived. In 1884, four years after his graduation, Alice delivered a daughter. Owing to complications, she died in childbirth on the very same day as the death of his mother.

A Rising Star

Devastated, he withdrew to North Dakota Territory, but could not live without the New York pace for long. Returning to New York in 1886, Roosevelt remarried and dedicated his life to public service. By 1898, he compiled an impressive resumé including

- Member of the Civil Service Commission

- Police Commissioner of New York City

- Assistant Secretary to the Navy.

Theodore Roosevelt's much-heralded charge up Cuba's San-Juan Hill made him into a national hero.

When the SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR erupted, he helped form a volunteer regiment called the ROUGH RIDERS. His success in the war led to the governor's office and then the Vice-Presidency.

Up to this point, the Vice-President had little power, and few had gone on to the White House unless a tragedy befell the President. Many Republican leaders supported Roosevelt in the number-two job for this very reason. They feared his headstrong style and maverick attitude. Their greatest fears were realized when a bullet ended President McKinley's life on September 13, 1901.

A New Kind of President

Soon it was clear that a new type of President was in town. The Presidency had been dormant since Lincoln's time. Congress seemed to be running the government, and big business seemed to be running Congress.

Philosophically, Roosevelt was outraged by these realities. Although he himself hailed from the wealthy classes, he strongly believed that no individual, no matter how rich and powerful, should control the people's representatives.

Furthermore, Roosevelt was convinced that if abuse of workers continued to go unchecked, a violent revolution would sweep the nation. An outspoken foe of socialism, Roosevelt believed that capitalism would be preserved with a little restraint and common sense. Within months he began to wield his newfound power.

Roosevelt changed the office in other important ways. He never went anywhere without his photographer. He wanted Americans to see a rough and tumble leader who was unafraid to get his hands dirty. He became the first President to travel out of the country while in office and the first to win theNOBEL PRIZE.

Unlike his quieter predecessors, Roosevelt knew that if the Washington politicians resisted change, he would have to take his case to the people directly. He traveled often and spoke with confidence and enthusiasm. Americans received him warmly.

The country was thirsting for leadership and Roosevelt became a political and popular hero. Merchandise was sold in his likeness, paintings and lithographs created in his honor, and even a film was produced portraying him as a fairy-tale hero. The White House was finally back in business.

The Trust Buster

Teddy Roosevelt was one American who believed a revolution was coming.

He believed WALL STREET FINANCIERS and powerful trust titans to be acting foolishly. While they were eating off fancy china on mahogany tables in marble dining rooms, the masses were roughing it. There seemed to be no limit to greed. If docking wages would increase profits, it was done. If higher railroad rates put more gold in their coffers, it was done. How much was enough, Roosevelt wondered?

The Sherman Anti-Trust Act

Although he himself was a man of means, he criticized the wealthy class of Americans on two counts. First, continued exploitation of the public could result in a violent uprising that could destroy the whole system. Second, the captains of industry were arrogant enough to believe themselves superior to the elected government. Now that he was President, Roosevelt went on the attack.

The President's weapon was the SHERMAN ANTITRUST ACT, passed by Congress in 1890. This law declared illegal all combinations "in restraint of trade." For the first twelve years of its existence, the Sherman Act was a paper tiger. United States courts routinely sided with business when any enforcement of the Act was attempted.

For example, the AMERICAN SUGAR REFINING COMPANY controlled 98 percent of the sugar industry. Despite this virtual monopoly, the Supreme Court refused to dissolve the corporation in an 1895 ruling. The only time an organization was deemed in restraint of trade was when the court ruled against a labor union

Roosevelt knew that no new legislation was necessary. When he sensed that he had a sympathetic Court, he sprung into action.

Teddy vs. J.P.

Theodore Roosevelt was not the type to initiate major changes timidly. The first trust giant to fall victim to Roosevelt's assault was none other than the most powerful industrialist in the country — J. Pierpont Morgan.

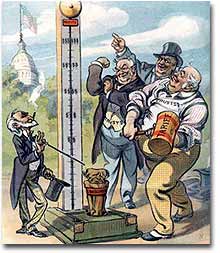

This 1912 cartoon shows trusts smashing consumers with the tariff hammer in hopes of raising profits.

Morgan controlled a railroad company known as Northern Securities. In combination with railroad MOGULSJAMES J. HILL and E. H. HARRIMAN, Morgan controlled the bulk of railroad shipping across the northern United States.

Morgan was enjoying a peaceful dinner at his New York home on February 19, 1902, when his telephone rang. He was furious to learn that Roosevelt's Attorney General was bringing suit against the Northern Securities Company. Stunned, he muttered to his equally shocked dinner guests about how rude it was to file such a suit without warning.

Four days later, Morgan was at the White House with the President. Morgan bellowed that he was being treated like a common criminal. The President informed Morgan that no compromise could be reached, and the matter would be settled by the courts. Morgan inquired if his other interests were at risk, too. Roosevelt told him only the ones that had done anything wrong would be prosecuted.

The Good, the Bad, and the Bully

This was the core of Theodore Roosevelt's leadership. He boiled everything down to a case of right versus wrong and good versus bad. If a trust controlled an entire industry but provided good service at reasonable rates, it was a "good" trust to be left alone. Only the "bad" trusts that jacked up rates and exploited consumers would come under attack. Who would decide the difference between right and wrong? The occupant of the White House trusted only himself to make this decision in the interests of the people.

The American public cheered Roosevelt's new offensive. The Supreme Court, in a narrow 5 to 4 decision, agreed and dissolved the Northern Securities Company. Roosevelt said confidently that no man, no matter how powerful, was above the law. As he landed blows on other "bad" trusts, his popularity grew and grew.

A Helping Hand for Labor

John Mitchell led the United Mine Workers through the 5-1/2 month long anthracite coal strike of 1902.

Workers rarely found a helping hand in the White House. President Hayes ordered the army to break the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. President Cleveland ordered federal troops to disrupt the Pullman Strike of 1894. Governors and mayors used the National Guard and police to confront workers on strike.

When Pennsylvania coal miners went on strike in 1902, there was no reason to believe anything had changed. But this time things were different. Teddy Roosevelt was in the White House.

Miners and Owners at Loggerheads

JOHN MITCHELL, president of the UNITED MINE WORKERS, represented the miners. He was soft-spoken, yet determined. Many compared his manner to Abraham Lincoln's. In the spring of 1902, Mitchell placed a demand on the coal operators for better wages, shorter hours, and recognition of the union. The owners, led by GEORGE BAER, flatly refused. On May 12, 1902, 140,000 miners walked off the job, and the strike was on.

Mitchell worked diligently behind the scenes to negotiate with Baer, but his efforts were rejected. According to Baer, there would be no compromise. Even luminaries such Mark Hanna and J.P. Morgan prevailed in vain on the owners to open talks. As the days passed, the workers began to feel the pinch of the strike, and violence began to erupt.

Soon summer melted into fall, and President Roosevelt wondered what the angry workers and a colder public would do if the strike lasted into the bitter days of winter. He decided to lend a hand in settling the strike.

Teddy the Arbitrator

No President had ever tried to negotiate a strike settlement before. Roosevelt invited Mitchell and Baer to the White House on October 3 to hammer out a compromise. Mitchell proposed to submit to an arbitration commission and abide by the results if Baer would do the same. Baer resented the summons by the President to meet a "common criminal" like Mitchell, and refused any sort of concession.

Roosevelt despaired that the violence would increase and spiral dangerously toward a class-based civil war. After the mine operators left Washington, he vowed to end the strike. He was impressed by Mitchell's gentlemanly demeanor and irritated by Baer's insolence. Roosevelt remarked that if he weren't president, he would have thrown Baer out of a White House window.

This frightening-looking structure is a coalbreaker, located in Scranton, PA.

He summoned his War Secretary, ELIHU ROOT, and ordered him to prepare the army. This time, however, the army would not be used against the strikers. The coal operators were informed that if no settlement were reached, the army would seize the mines and make coal available to the public. Roosevelt did not seem to mind that he had no constitutional authority to do any such thing.

Compromise

J.P. Morgan finally convinced Baer and the other owners to submit the dispute to a commission. On October 15, the strike ended. The following March, a decision was reached by the mediators. The miners were awarded a 10 percent pay increase, and their workday was reduced to eight or nine hours. The owners were not forced to recognize the United Mine Workers.

Workers across America cheered Roosevelt for standing up to the mine operators. It surely seemed like the White House would lend a helping hand to the labor movement.

Preserving the Wilderness

As America grew, Americans were destroying its NATURAL RESOURCES. Farmers were depleting the nutrients of the overworked soil. Miners removed layer after layer of valuable topsoil, leading to catastrophic erosion. Everywhere forests were shrinking and wildlife was becoming more scarce.

The Sierra Club

The growth of cities brought a new interest in preserving the old lands for future generations. Dedicated to saving the wilderness, the SIERRA CLUB formed in 1892. JOHN MUIR, the president of the Sierra Club, worked valiantly to stop the sale of public lands to private developers. At first, most of his efforts fell on deaf ears. Then Theodore Roosevelt inhabited the Oval Office, and his voice was finally heard.

Roosevelt Protects Public Lands

Roosevelt was an avid outdoorsman. He hunted, hiked, and camped whenever possible. He believed that living in nature was good for the body and soul. Although he proved willing to compromise with Republican conservatives on many issues, he was dedicated to protecting the nation's public lands.

The first measure he backed was the NEWLANDS RECLAMATION ACT OF 1902. This law encouraged developers and homesteaders to inhabit lands that were useless without massive irrigation works. The lands were sold at a cheap price if the buyer assumed the cost of irrigation and lived on the land for at least five years. The government then used the revenue to irrigate additional lands. Over a million barren acres were rejuvenated under this program.

Yellowstone's Tower Falls and Sulphur Mountain, one of the earliest tracts of preserved wilderness in America.

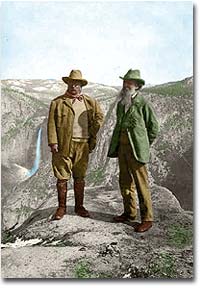

John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt were more than political acquaintances. In 1903, Roosevelt took a vacation by camping with Muir in YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK. The two agreed that making efficient use of public lands was not enough. Certain wilderness areas should simply be left undeveloped.

Under an 1891 law that empowered the President to declare national forests and withdraw public lands from development, Roosevelt began to preserve wilderness areas. By the time he left office 150,000,000 acres had been deemed national forests, forever safe from the ax and saw. This amounted to three times the total protected lands since the law was enacted.

In 1907, Congress passed a law blocking the President from protecting additional territory in six western states. In typical Roosevelt fashion, he signed the bill into law — but not before protecting 16 million additional acres in those six states.

Conservation Fever

Conservation fever spread among urban intellectuals as a result. By 1916, there were sixteen national parks with over 300,000 annual visitors. The BOY SCOUTS and GIRL SCOUTS formed to give urban youths a greater appreciation of nature. Memberships in conservation and wildlife societies soared.

Teddy Roosevelt distinguished himself as the greatest Presidential advocate of the environment since Thomas Jefferson. Much damage had been done, but America's beautiful, abundant resources were given a new lease on life.

Passing the Torch

1908 was not a good year for Teddy Roosevelt. The nation was recovering from a FINANCIAL PANIC that had rocked Wall Street the previous year. Many leading industrialists unjustly blamed the crisis on the President. The Congress that he had finessed in his early term was now dominated by conservative Republicans who took joy at blocking the President's initiatives. Now his time in the White House was coming to a close.

He had promised not to seek a third term when he was elected in 1904. No prior President had ever broken the two-term tradition. Roosevelt would keep his word.

Among Friends

He decided that if he could no longer serve as President, the next best option was to name a successor that would carry out his programs. He found the perfect candidate in WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT.

Taft and Roosevelt were best friends. When Roosevelt was sworn in as chief executive, Taft was serving as governor of the Philippines. Roosevelt offered his friend a seat on the Supreme Court, but his work in the Philippines and the ambitions of Mrs. Taft propelled him to decline. In 1904, he became Secretary of War and his friendship with Roosevelt grew stronger.

By 1908, Roosevelt was convinced that Taft would be the ideal successor. His support streamrollered Taft to the Republican nomination, and the fall election against the tired William Jennings Bryan proved to be a landslide victory.

Juggling Progressives and Conservatives

Upon leaving the White House, Roosevelt embarked on a worldwide tour, including an African safari and a sojourn through Europe. Taft was left to make his own mark on America. But he lacked the political skill of his predecessor to keep both the progressive and conservative wings of his party happy. Soon he would alienate one side or the other.

Unfortunately, Taft is probably most famous for getting stuck in his bathtub. His obvious obesity helped change American attitudes toward fitness.

The defining moment came with the PAYNE-ALDRICH TARIFF. Progressives hated the measure, which raised rates, and conservatives lauded it. Taft signed the bill, and his progressive supporters were furious.

The rupture widened with theBALLINGER-PINCHOT controversy.RICHARD BALLINGEr was Taft's Secretary of the Interior. His appointment shocked GIFFORD PINCHOT, the nation's chief forester and longtime companion of Theodore Roosevelt. Pinchot rightly saw that Ballinger was no friend to Roosevelt's conservation initiatives. When Pinchot publicly criticized Ballinger, Taft fired Pinchot, and progressives were again outraged. The two wings of the party were now firmly on a collision course.

Taft's Progressive Reforms

Despite criticism from progressive Republicans, Taft did support many of their goals. He broke twice as many trusts in his one term as Roosevelt had broken in his two. Taft limited the workday of federal employees to 8 hours and supported the 16th Amendment to the Constitution, which empowered the Congress to levy a federal income tax. He also created a Children's Bureau and supported the 17th Amendment, which allowed for senators to be directly elected by the people instead of the state legislatures.

Still, when Roosevelt returned to America, progressives pressed him to challenge Taft for the party leadership. As 1912 approached, the fight was on.

The Election of 1912

Politics can sometimes turn the best of friends into the worst of enemies. Such was the fate for the relationship between Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.

Roosevelt's decision to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912 was most difficult. Historians disagree on his motives. Defenders of Roosevelt insist that Taft betrayed the progressive platform. When Roosevelt returned to the United States, he was pressured by thousands of progressives to lead them once more. Roosevelt believed that he could do a better job uniting the party than Taft. He felt a duty to the American people to run.

Critics of Roosevelt are not quite so kind. Roosevelt had a huge ego, and his lust for power could not keep him on the sidelines. He stabbed his friend in the back and overlooked the positive sides of Taft's Presidency. Whatever the motive, the election of 1912 would begin with two prominent Republican candidates.

The two former friends hurled insults at each other as the summer of 1912 drew near. Taft had the party leadership behind him, but Roosevelt had the people. Roosevelt spoke of a NEW NATIONALISM — a broad plan of social reform for America.

Rather than destroying every trust, Roosevelt supported the creation of aFEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION to keep a watchful eye on unfair business practices. He proposed a minimum wage, a workers' compensation act, and a child labor law. He proposed a government pension for retirees and funds to assist Americans with health care costs. He supported the women's suffrage amendment. The time of laissez faire was over. The government must intervene to help its people.

Taft and his supporters disagreed, and the battle was left for the delegates to decide.

Woodrow Wilson's New Freedom

President Wilson

Progressives did not come only in the Republican flavor. THOMAS WOODROW WILSON also saw the need for change.

Born in Staunton, Virginia, Wilson served as president of Princeton University and governor of New Jersey. He combined a southern background with northern sensibilities.

Attacking the Triple Wall of Privilege

His 1912 platform for change was called the NEW FREEDOM. Wilson was an admirer of Thomas Jefferson. The agrarian utopia of small, educated farmers envisioned by Jefferson struck a chord with Wilson. Of course, the advent of industry could not be denied, but a nation of small farmers and small businesspeople seemed totally possible. The New Freedom sought to achieve this vision by attacking what Wilson called the TRIPLE WALL OF PRIVILEGE — the tariff, the banks, and the trusts.

Tariffs protected the large industrialists at the expense of small farmers. Wilson signed the UNDERWOOD-SIMMONS ACT into law in 1913, which reduced tariff rates. The banking system also pinched small farmers and entrepreneurs. The gold standard still made currency too tight, and loans were too expensive for the average American. Wilson signed the FEDERAL RESERVE ACT, which made the nation's currency more flexible.

Unlike Roosevelt, Wilson did not distinguish between "good" trusts and "bad" trusts. Any trust by virtue of its large size was bad in Wilson's eyes. TheCLAYTON ANTITRUST ACT OF 1914 clarified the Sherman Act by specifically naming certain business tactics illegal. This same act also exempted labor unions from antitrust suits, and declared strikes, boycotts, and peaceful picketing perfectly legal.

In two years, he successfully attacked each "wall of privilege." Now his eyes turned to greater concerns, particularly the outbreak of the FIRST WORLD WAr in Europe.

Appeasing the Bull Moose

When Wilson's first term expired, he felt he had to do more. The nation was on the brink of entering the bloodiest conflict in human history, and Wilson had definite ideas about how the postwar peace should look. But he would have to survive reelection first.

As an appeal to the Roosevelt progressives, he began to sign many legislative measures suggested by the BULL MOOSE CAMPAIGN. He approved of the creation of a federal trade commission to act as a watchdog over business. A child labor bill and a workers' compensation act became law. Wilson agreed to limit the workday of interstate railroad workers to 8 hours. He signed aFEDERAL FARM LOAN ACT to ease the pains of life on the farm.

Progressive Republicans in the Congress were pleased by Wilson's conversion to their brand of progressivism, and the American people showed their approval by electing him to a second term.