Reading: Reading: Seeking Empire

Seeking Empire

Since the early days of Jamestown colony, Americans were constantly stretching their boundaries to encompass more territory. When the United States government was formed, the practice continued. The first half of the 19th century was spent defining the nation's borders through negotiation and war, and the second half was spent populating the fruits of the labor. As the 20th century dawned, many believed that the expansion should continue.

Many different groups pushed for AMERICAN EXPANSION OVERSEAS. Industrialists sought new markets for their products and sources for cheaper resources. Nationalists claimed that colonies were a hallmark of national prestige. The European powers had already claimed much of the globe; America would have to compete or perish. Missionaries continually preached to spread their messages of faith. Social Darwinists such as Josiah Strong believed that American civilization was superior to others and that it was an American's duty to diffuse its benefits. Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote an influential thesis declaring that throughout history, those that controlled the seas controlled the world. Acquiring naval bases at strategic points around the world was imperative.

Before 1890, American lands consisted of little more than the contiguous states and Alaska. By the end of World War I, America could boast a global empire. American Samoa and Hawaii were added in the 1890s by force. The Spanish-American War brought Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines under the American flag. The ROOSEVELT COROLLARY to the Monroe Doctrine declared the entire western hemisphere an American sphere of influence. Through initial negotiation and eventual intimidation, the United States secured the rights to build and operate an isthmathian canal in Panama. The German naval threat in World War I prompted the purchase of the VIRGIN ISLANDSfrom Denmark in 1917.

The country that had once fought to throw off imperial shackles was now itself an empire. With the economic and strategic benefits came the expected difficulties. Filipinos fought a bloody struggle for independence. America became entangled with distant conflicts to defend the new claims. Regardless of the nobility or self-interest of the intent, the United States was now poised to claim its role as a world power in the 20th century.

Early Stirrings

Manifest destiny did not die when Americans successfully lay claim to the West Coast. The newly won territory was the source of heated argument in the 1850s and a major reason for the War Between the States. Once the Union was patched back together, Americans were mostly content with settling the land already under the United States flag. But as the decades passed and America grew strong with industrial might, the desire to spread the eagle's wings over additional territory came back into vogue. Between 1890 and the start of World War I, the United States earned a seat at the table of imperial powers.

Purchase of Alaska

When WILLIAM SEWARD proposed the purchase of ALASKA in 1867, his peers thought he had gone mad. RUSSIAN AMERICA, as it was called, was a vast frozen wasteland surely not worth 7.2 million American dollars. "SEWARD'S FOLLY," some scoffed. "SEWARD'S ICEBOX," others razzed. The Senate saw the potential of its vast natural resources and approved the treaty, but the House stalled the purchase of the "Polar Bear Garden" for over a year. Not too much attention was paid to the new acquisition at first. Americans were too busy mending the fractured Union and then settling the continental West.

Five Near Wars

By the middle of the 1890s, it was clear that Americans were looking outward. Five near wars dotted the first half of the decade. The SAMOAN ISLANDS of the South Pacific were coveted by Britain, Germany, and the United States. In 1889, the American and German navies almost exchanged gunfire before a settlement dividing the islands among the three powers could be reached. In 1891, when eleven Italians were brutally lynched in New Orleans, the United States approached a state of war with Italy before a compromise was arranged. A similar situation erupted the following year inCHILE. This time, two American sailors were killed in a bar in VALPARAISO. The United States government forced the Chileans to pay compensation to avoid war. Even our neighbors to the North were not immune. A fracas over seal hunting rights near Alaska caused tempers to flare. In 1895, Great Britain insisted that the boundary of its BRITISH GUIANA colony included gold-enriched forest land that was also claimed by Venezuela. President Cleveland cited the Monroe Doctrine as a reason to keep the British in their own hemisphere. Threatening war with Britain if they failed to submit their claim to arbitration, the United States defended its influence in the Western Hemisphere.

The signs were clear. It had been fifty years since the United States had waged war with a foreign power, and Americans seemed to be in the mood for a fight. Little disturbances involving the likes of VENEZUELA, Chile, and American Samoa would not sate the desire to expand or prove America's new strength to the entire world. Soon new territories were seized, and the war that seemed inevitable finally arrived.

Hawaiian Annexation

By the time the United States got serious about looking beyond its own borders to conquer new lands, much of the world had already been claimed. Only a few distant territories in Africa and Asia and remote islands in the Pacific remained free from imperial grasp. Hawaii was one such plum. Led by a hereditary monarch, the inhabitants of the kingdom prevailed as an independent state. American expansionists looked with greed on the strategically located islands and waited patiently to plan their move.

Foothold in Hawaii

Interest in HAWAII began in America as early as the 1820s, when New England missionaries tried in earnest to spread their faith. Since the 1840s, keeping European powers out of Hawaii became a principal foreign policy goal. Americans acquired a true foothold in Hawaii as a result of the SUGAR TRADE. The United States government provided generous terms to Hawaiian sugar growers, and after the Civil War, profits began to swell. A turning point in U.S.-Hawaiian relations occurred in 1890, when Congress approved theMCKINLEY TARIFF, which raised import rates on foreign sugar. Hawaiian sugar planters were now being undersold in the American market, and as a result, a depression swept the islands. The sugar growers, mostly white Americans, knew that if Hawaii were to be ANNEXED by the United States, the tariff problem would naturally disappear. At the same time, the Hawaiian throne was passed to QUEEN LILIUOKALANI, who determined that the root of Hawaii's problems was foreign interference. A great showdown was about to unfold.

Annexing Hawaii

In January 1893, the planters staged an uprising to overthrow the Queen. At the same time, they appealed to the United States armed forces for protection. Without Presidential approval, marines stormed the islands, and the American minister to the islands raised the stars and stripes in HONOLULU. The Queen was forced to abdicate, and the matter was left for Washington politicians to settle. By this time, Grover Cleveland had been inaugurated President. Cleveland was an outspoken anti-imperialist and thought Americans had acted shamefully in Hawaii. He withdrew the annexation treaty from the Senate and ordered an investigation into potential wrongdoings. Cleveland aimed to restore Liliuokalani to her throne, but American public sentiment strongly favored annexation.

The matter was prolonged until after Cleveland left office. When war broke out with Spain in 1898, the military significance of Hawaiian naval bases as a way station to the SPANISH PHILIPPINES outweighed all other considerations. President William McKinley signed a joint resolution annexing the islands, much like the manner in which Texas joined the Union in 1845. Hawaii remained a territory until granted statehood as the fiftieth state in 1959.

"Remember the Maine!"

There was more than one way to acquire more land. If the globe had already been claimed by imperial powers, the United States could always seize lands held by others. Americans were feeling proud of their growing industrial and military prowess. The long-dormant Monroe Doctrine could finally be enforced. Good sense suggested that when treading on the toes of empires, America should start small. In 1898, Spain was weak and Americans knew it. Soon the opportunity to strike arose.

Involvement in Cuba

CUBA became the nexus of Spanish-American tensions. Since 1895, Cubans had been in open revolt against Spanish rule. The following year, Spain sent GENERAL VALERIANO WEYLER to Cuba to sedate the rebels. Anyone suspected of supporting independence was removed from the general population and sent to concentration camps. Although few were summarily executed, conditions at the camps led over 200,000 to die of disease and malnutrition. The news reached the American mainland through the newspapers of the yellow journalists. William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were the two most prominent publishers who were willing to use sensational headlines to sell papers. Hearst even sent the renowned painterFREDERICK REMINGTON to Cuba to depict Spanish misdeeds. The American public was appalled.

The Maine Sinks

In February 1898, relations between the United States and Spain deteriorated further. DUPUY DE LÔME, the Spanish minister to the United States had written a stinging letter about President McKinley to a personal friend. The letter was stolen and soon found itself on the desk of Hearst, who promptly published it on February 9. After public outcry, de Lôme was recalled to Spain and the Spanish government apologized. The peace was short-lived, however. On the evening of February 15, a sudden and shocking explosion tore a hole in the hull of the American battleship MAINE, which had been on patrol in HAVANA HARBOR. The immediate assumption was that the sinking of the Maine and the concomitant deaths of 260 sailors was the result of Spanish treachery. Although no conclusive results have ever been proven, many Americans had already made up their minds, demanding an immediate declaration of war.

McKinley proceeded with prudence at first. When the Spanish government agreed to an armistice in Cuba and an end to concentration camps, it seemed as though a compromise was in reach. But the American public, agitated by the yellow press and American imperialists, demanded firm action. "REMEMBER THE MAINE, TO HELL WITH SPAIN!" was the cry. On April 11, 1898, McKinley asked the Congress for permission to use force in Cuba. To send a message to the rest of the world that the United States was interested in Cuban independence instead of American colonization, Congress passed the TELLER AMENDMENT, which promised that America would not annex the precious islands. After that conscience-clearing measure, American leaders threw caution to the wind and declared open warfare on the Spanish throne.

The Spanish-American War and Its Consequences

Americans aboard the Olympia prepare to fire on Spanish ships during the Battle of Manila Bay, May 1, 1898.

The United States was simply unprepared for war. What Americans had in enthusiastic spirit, they lacked in military strength. The navy, although improved, was simply a shadow of what it would become by World War I. The UNITED STATES ARMYwas understaffed, underequipped, and undertrained. The most recent action seen by the army was fighting the Native Americans on the frontier. Cuba required summer uniforms; the US troops arrived with heavy woolen coats and pants. The food budget paid for substandard provisions for the soldiers. What made these daunting problems more managable was one simple reality. Spain was even less ready for war than the United States.

Battle of Manila Bay

Prior to the building of the Panama Canal, each nation required a two-ocean navy. The major portion of Spain's Pacific fleet was located in the Spanish Philippines at MANILA BAY. Under orders from Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, ADMIRAL GEORGE DEWEY descended upon the Philippines prior to the declaration of war. Dewey was in the perfect position to strike, and when given his orders to attack on May 1, 1898, the American navy was ready. Those who look back with fondness on American military triumphs must count the BATTLE OF MANILA BAY as one of the greatest success stories. The larger, wooden Spanish fleet was no match for the newer American steel navy. After Dewey's guns stopped firing, the entire Spanish squadron was a hulking disaster. The only American casualty came from sunstroke. The Philippines remained in Spanish control until the army had been recruited, trained, and transported to the Pacific.

Invading Cuba

The situation in Cuba was far less pretty for the Americans. At the outbreak of war the United States was outnumbered 7 to 1 in army personnel. The invading force led by GENERAL WILLIAM SHAFTER landed rather uneventfully near SANTIAGO. The real glory of the Cuban campaign was grabbed by the Rough Riders. Comprising cowboys, adventurous college students, and ex-convicts, the Rough Riders were a volunteer regiment commanded byLEONARD WOOD, but organized by Theodore Roosevelt. Supported by two African American regiments, the Rough Riders charged up SAN JUAN HILL and helped Shafter bottle the Spanish forces in Santiago harbor. The war was lost when the Spanish Atlantic fleet was destroyed by the pursuing American forces.

Treaty of Paris

The TREATY OF PARIS was most generous to the winners. The United States received the Philippines and the islands of GUAM and PUERTO RICO. Cuba became independent, and Spain was awarded $20 million dollars for its losses. The treaty prompted a heated debate in the United States. ANTI-IMPERIALISTS called the US hypocritical for condemning European empires while pursuing one of its own. The war was supposed to be about freeing Cuba, not seizing the Philippines. Criticism increased when Filipino rebels led by Emilio Aguinaldo waged a 3-year insurrection against their new American colonizers. While the Spanish-American War lasted ten weeks and resulted in 400 battle deaths, the PHILIPPINE INSURRECTION lasted nearly three years and claimed 4000 American lives. Nevertheless, President McKinley's expansionist policies were supported by the American public, who seemed more than willing to accept the blessings and curses of their new expanding empire.

The Roosevelt Corollary and Latin America

For many years, the Monroe Doctrine was practically a dead letter. The bold proclamation of 1823 that declared the Western Hemisphere forever free from European expansion bemused the imperial powers who knew the United States was simply too weak to enforce its claim. By 1900, the situation had changed. A bold, expanding America was spreading its wings, daring the old world order to challenge its newfound might. When Theodore Roosevelt became President, he decided to reassert Monroe's old declaration.

The Platt Amendment

Cuba became the foundation for a new LATIN AMERICAN POLICY. Fearful that the new nation would be prey to the imperial vultures of Europe, United States diplomats sharpened American talons on the island. In the PLATT AMENDMENT OF 1901, Cuba was forbidden from entering any treaty that might endanger their independence. In addition, to prevent European gunboats from landing on Cuban shores, Cuba was prohibited from incurring a large debt. If any of these conditions were violated, Cuba agreed to permit American troops to land to restore order. Lastly, the United States was granted a lease on a naval base at GUANTANAMO BAY. Independent in name only, Cuba became a legalPROTECTORATE of the United States.

Roosevelt Corollary

Convinced that all of Latin America was vulnerable to European attack, President Roosevelt dusted off the Monroe Doctrine and added his own corollary. While the Monroe Doctrine blocked further expansion of Europe in the Western Hemisphere, the Roosevelt Corollary went one step further. Should any Latin American nation engage in "CHRONIC WRONGDOING," a phrase that included large debts or civil unrest, the United States military would intervene. Europe was to remain across the Atlantic, while America would police the Western Hemisphere. The first opportunity to enforce this new policy came in 1905, when the DOMINICAN REPUBLIC was in jeopardy of invasion by European debt collectors. The United States invaded the island nation, seized its customs houses, and ruled the Dominican Republic as a protectorate until the situation was stablilized.

A Big Stick

The effects of the new policy were enormous. Teddy Roosevelt had a motto: "SPEAK SOFTLY AND CARRY A BIG STICK." To Roosevelt, the big stick was the new American navy. By remaining firm in resolve and possessing the naval might to back its interests, the United States could simultaneously defend its territory and avoid war. Latin Americans did not look upon the corollary favorably. They resented U.S. involvement as YANKEE IMPERIALISM, and animosity against their large neighbor to the North grew dramatically. By the end of the 20th century, the United States would send troops of invasion to Latin America over 35 times, establishing an undisputed sphere of influence throughout the hemisphere.

Reaching to Asia

Marine and sailors with Colt machine gun, Boxer Rebellion, 1900

The United States could not ignore the largest continent on earth forever. SinceCOMMODORE MATTHEW PERRY "opened" Japan in 1854, trade with Asia was a reality, earning millions for American merchants and manufacturers. Slowly but surely the United States acquired holdings in the region, making the ties even stronger. Already Alaska, Hawaii, and American Samoa flew the American flag. The Spanish-American War brought Guam and the Philippines as well. These territories needed supply routes and defense, so ports of trade and naval bases became crucial.

Open Door Policy

The most populous nation on earth was already divided between encroaching European empires. China still had an emperor and system of government, but the foreign powers were truly in control. Although the Chinese Empire was not carved into colonies such as Africa, Europe did establish quasi-colonial entities called SPHERES OF INFLUENCE after 1894. Those enjoying special privileges in this fashion included Great Britain, France, Russia, Germany, and Japan. Secretary of State John Hay feared that if these nations established trade practices that excluded other nations, American trade would suffer. Britain agreed and Hay devised a strategy to preserve open trade. He circulated letters among all the powers called OPEN DOOR NOTES, requesting that all nations agree to free trade in China. While Britain agreed, all the other powers declined in private responses. Hay, however, lied to the world and declared that all had accepted. The imperial powers, faced with having to admit publicly to greedy designs in China, remained silent and the Open Door went into effect.

The Boxer Rebellion

In 1900, foreign occupation of China resulted in disaster. A group of Chinese nationalists called the FISTS OF RIGHTEOUS HARMONY attacked Western property. The BOXERS, as they were known in the West, continued to wreak havoc until a multinational force invaded to stop the uprising. The BOXER REBELLION marked the first time United States armed forces invaded another continent without aiming to acquire the territory. The rebels were subdued, and China was forced to pay an indemnity of $330 million to the United States.

Nobel Peace Prize for Roosevelt

Japan was also a concern for the new imperial America. In 1904, war broke out between RUSSIA AND JAPAN. The war was going poorly for the Russians. Theodore Roosevelt offered to mediate the peace process as the war dragged on. The two sides met with Roosevelt in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and before long, a treaty was arranged. Despite agreeing to its terms, the Japanese public felt that Japan should have been awarded more concessions. Anti-American rioting swept the island. Meanwhile, Roosevelt was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. This marked the first time an American President received such an offer.

Relations with Japan remained icy. In California, JAPANESE IMMIGRANTS to America were faced with harsh discrimination, including segregated schooling. In the informal GENTLEMAN'S AGREEMENT OF 1907, the United States agreed to end the practice of separate schooling in exchange for a promise to end Japanese immigration. That same year, Roosevelt decided to display his "big stick," the new American navy. He sent the flotilla, known around the world as the GREAT WHITE FLEET, on a worldwide tour. Although it was meant to intimidate potential aggressors, particularly Japan, the results of the journey were uncertain. Finally, in 1908, Japan and the United States agreed to respect each other's holdings on the Pacific Rim in the ROOT-TAKAHIRA AGREEMENT. Sending troops overseas, mediating international conflicts, and risking trouble to maintain free trade, the United States began to rapidly shed its ISOLATIONIST past.

The Panama Canal

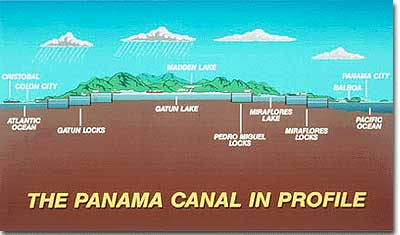

A view of the Panama Canal in profile, showing the placement of the locks.

A canal was inevitable. A trip by boat from New York to San Francisco forced a luckless crew to sail around the tip of South America — a journey amounting to some 12,000 miles. The new empire might require a fast move from the Atlantic to the Pacific by a naval squadron. Teddy Roosevelt decided that the time for action was at hand. The canal would be his legacy, and he would stop at nothing to get it.

First Obstacles

There were many obstacles to such a project. The first was Great Britain. Fearing that either side would build an isthmathian canal and use it for national advantage, the United States and Great Britain agreed in the 1850CLAYTON-BULWER TREATY that neither side would build such a canal. A half century later, the now dominant United States wanted to nullify this deal. Great Britain, nervous about its SOUTH AFRICAN BOER WAR and an increasingly cloudy Europe, sought to make a friend in the United States. The HAY-PAUNCEFOTE TREATY permitted the United States to build and fortify a Central American canal, so long as the Americans promised to charge the same fares to all nations. One roadblock was clear.

Selecting Panama

The next question was where to build. FERDINAND DE LESSUPS, the same engineer who designed the SUEZ CANAL, had organized a French attempt in Panama in the 1870s. Disease and financial problems left a partially built canal behind. While it made sense that the United States should buy the rights to complete the effort, Panama posed other problems. Despite being the most narrow nation in the region, Panama was very mountainous, and a complex series of locks was necessary to move ships across the isthmus. Nicaragua was another possibility. The canal would be situated closer to the United States. The terrain was flatter, and despite Nicaragua's width, there were numerous lakes that could be connected. Volcanic activity in Nicaragua prompted the United States to try to buy the territory in Panama.

But Panama was not an independent state. To obtain the rights to the territory, the United States had to negotiate with Colombia. The 1903 HAY-HERRAN TREATY permitted the United States to lease a six-mile wide strip of land at an annual fee. The treaty moved through the United States Senate, but the Colombian Senate held out for more money. Roosevelt was furious. Determined to build his canal, Roosevelt sent a U.S. gunboat to the shores of Colombia. At the same time, a group of "revolutionaries" declared independence in Panama. The Colombians were powerless to stop the uprising. The United States became the first nation in the world to recognize the new government of Panama. Within weeks, the HAY–BUNAU-VARILLA TREATY awarded a 10-mile strip of land to the United States, and the last hurdle was cleared.

Constructing the Canal

Or so it seemed. Construction on the canal was extremely difficult. The world had never known such a feat of engineering. Beginning in 1907, American civilians blasted through tons of mountain stone. Thanks to the work ofWALTER REED and WILLIAM GORGAS, the threats of yellow fever and MALARIAwere greatly diminished. When Theodore Roosevelt visited the blast area, he became the first sitting American President to travel outside the country. Finally, the deed was done. In 1914, at the cost of $345 million, the PANAMA CANAL was open for business.