Reading: The Road to Pearl Harbor

The Road to Pearl Harbor

Japanese bombers fire on the USS Nevada at Pearl Harbor. The surprise attack of December 7, 1941, left President Roosevelt with no choice but to enter World War II.

Storm clouds were darkening around the world. While Americans struggled to make ends meet during the Great Depression, fascism swept Italy and Germany. Elsewhere, militarists consolidated their hold on the Japanese government. Soon fears of fascist domination were realized as nations fell, hapless victims to new aggressive leaders. Remembering the scars caused by WORLD WAR I, Americans hoped against hope to remain aloof from the increasingly dangerous world.

Japan struck first, plunging into Chinese Manchuria. Next Italy struck at Ethiopia. Germany, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, was the greatest fear. The industrial potential of Germany was awesome, and the power of the German army to inflict great damage was all too fresh in the minds of Europeans and Americans alike. Like dominoes, the nations surrounding Germany began to fall. First Austria was annexed, then Czechoslovakia. As Hitler set his sights on Poland, the world braced itself for another great conflict.

Economic hard times around the globe led to the rise of fascist leaders like Adolf Hitler. Here, Hitler receives the salute of the Reichstag upon announcing the annexation of Austria.

Meanwhile, Americans clung to their time-tested philosophy of isolationism. A series of Neutrality Acts sought to avoid the entrapments that plunged the nation into World War I. Poll after poll showed an unwillingness to become diplomatically involved in international disputes. Isolationist clubs spread across the land.

Yet when Great Britain became the last bastion of freedom standing against a Nazi-controlled Europe, Americans reluctantly began to act. Led by President Roosevelt, the United States used its industrial might to become the arsenal of democracy for the Allied war effort.

In the end, it was Japan who provoked the United States into war. The United States was the only nation standing against Japanese domination of the entirePACIFIC RIM. When economic sanctions against Japan produced a diplomatic stalemate, Japan launched a ruthless surprise attack against American naval bases at Pearl Harbor. Faced with an assault on its own forces, the United States finally entered the Second World War.

1930s Isolationism

Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Good Neighbor Policy" was instituted to foster good relations from other countries within the same hemisphere. As a result, Marines stationed in the Caribbean — like those seen here — were withdrawn.

"Leave me alone," seemed to be America's attitude toward the rest of the world in the 1930s.

At the dawn of the '30s, foreign policy was not a burning issue for the average American. The stock market had just crashed and each passing month brought greater and greater hardships. American involvement with Europe had brought war in 1917 and unpaid debt throughout the 1920s. Having grown weary with the course of world events, citizens were convinced the most important issues to be tackled were domestic. Foreign policy leaders of the 1930s once again led the country down its well-traveled path of isolationism.

The Hoover Administration set the tone for an isolationist foreign policy with the Hawley-Smoot Tariff. Trade often dominated international relations and the protective wall of the tariff left little to discuss. The Far East became an area of concern when the Japanese government ordered an attack on CHINESE MANCHURIA. This invasion was a clear violation of the NINE POWER TREATY, which prohibited nations from carving a special sphere of influence in China.

Political boundaries in East Asia, seen here at the turn of the century, were increasingly challenged in the years leading up to World War II.

The Hoover Administration knew that any harsh action against JAPAN would be unpopular in the midst of the Great Depression. The official American response was the STIMSON DOCTRINE, which refused to recognize any territory illegally occupied by Japan. As meek as this may sound, it went further toward condemning Japan than the government of Great Britain was willing to do.

One possibility for international economic cooperation failed at the LONDON CONFERENCE OF 1933. Leaders of European nations hoped to increase trade and stabilize international currencies. Roosevelt sent a "BOMBSHELL MESSAGE" to the conference refusing any attempt to tie the American dollar to a gold standard. The conference dissolved with European delegates miffed at the lack of cooperation by the United States.

Roosevelt did realize that the Hawley-Smoot Tariff was forestalling American economic recovery. Toward this end, Congress did act to make United States trade policy more flexible. Under the Reciprocal Trade Agreement of 1934, Congress authorized the President to negotiate tariff rates with individual nations. Should a nation agree to reduce its barriers to trade with the United States, the President could reciprocate without the consent of Congress. In addition, FDR broke a 16-year-old diplomatic freeze with the SOVIET UNION by extending formal recognition. Roosevelt hoped to settle some nettlesome outstanding issues with the Soviets, and at the same time stimulate bilateral trade.

The Japanese attack on Chinese Manchuria was in direct violation of the Nine Powers Treaty, which had been passed to prevent nations from establishing a special sphere of influence in China. Here a Japanese tank rolls through Shanghai, China.

Isolationists did not however designate the Western Hemisphere as a dangerous region. On the contrary, as tensions grew in Europe and Asia, a strong sense of PAN-AMERICANISM swept the diplomatic circles. In the face of overseas adversity, strong hemispheric solidarity was attractive. To foster better relations with the nations to the south, Roosevelt declared a bold new GOOD NEIGHBOR POLICY. Marines stationed in Central America and the Caribbean were withdrawn. The (Theodore) ROOSEVELT COROLLARY, which proclaimed the right of the United States to intervene in Latin American affairs was renounced.

The United States would soon been intervening in something much bigger.

Reactions to a Troubled World

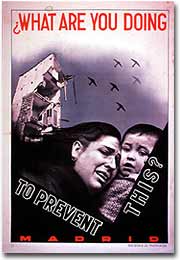

Volunteers from around the globe converged on Spain in the 1930s to help fend off a fascist uprising led by Francisco Franco. This poster, printed in Spanish, French, and English, is a plea for international support.

The day after Franklin Roosevelt took the oath of office the Nazi REICHSTAG gave ADOLF HITLER absolute control of Germany. Hitler had campaigned spewing ANTI-SEMITICrhetoric and vowing to rebuild a strong Germany.

During the week prior to FDR's inauguration, Japan withdrew from the League of Nations for the condemnation of Japanese aggressions in China. FASCISM andMILITARISM were spreading across Europe and East Asia. Meanwhile Americans were not bracing themselves for the coming war; they were determined to avoid it at all costs.

The first act of European aggression was not committed by Nazi Germany. FascistDICTATOR BENITO MUSSOLINI ordered the Italian army to invade ETHIOPIA in 1935. The League of Nations refused to act, despite the desperate pleas from Ethiopia's leader HAILE SELASSIE.

The following year Hitler and Mussolini formed the ROME-BERLIN AXIS, an alliance so named because its leaders believed that the line that connected the two capitals would be the axis around which the entire world would revolve. Later in 1936, Hitler marched troops into the Rhineland of Germany, directly breaching the TREATY OF VERSAILLES, which was signed after World War I. A few months later, Fascist GENERAL FRANCISCO FRANCO launched an attempt to overthrow the established LOYALIST government of SPAIN. Franco received generous support from Hitler and Mussolini.

Pablo Picasso created this mural for display in the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World's Fair. Entitled "Guernica," it depicts the slaughter of over 1,600 Spanish civilians by fascist forces.

While Fascist aggressors were chalking up victories across Europe, America, Britain, and France sat on the sidelines. The desire to avoid repeating the mistakes of World War I was so strong, no government was willing to confront the dictators. Economic sanctions were unpopular during the height of the Great Depression. The Loyalists in Spain were already receiving aid from the Soviet Union; therefore, public opinion was against assisting Moscow in its "private" war against fascism. As the specter of dictatorship spread across Europe, the West feebly objected with light rebukes and economic penalties with no teeth.

The United States Congress and President Roosevelt passed three important laws — all called NEUTRALITY ACTS — directly aimed at reversing the mistakes made that led to the American entry into the First World War.

The NEUTRALITY ACT OF 1935 prohibited the shipping of arms to nations at war, including the victims of aggressions. This would reduce the possibility of maritime attacks on American vessels. A Senate Committee led by Gerald Nye had conducted extensive research on US activities prior to World War I concluded that trade and international finance had been the leading cause of American entry.

The Neutrality Act of 1936 was designed to keep American citizens out of peril by forbidding them to travel on the ships of warring nations. More than 100 Americans were killed when a German submarine torpedoed the Lusitania in 1915.

The NEUTRALITY ACT OF 1936 renewed the law of the previous year with the additional restrictions — no loans could be made to belligerent nations. Nor were any Americans permitted to travel on the ships of nations at war. There would be no more LUSITANIA incidents.

A NEUTRALITY ACT OF 1937 limited the trade of even non-munitions to belligerent nations to a "CASH AND CARRY BASIS." This meant that the nation in question would have to use its ships to transport goods to avoid American entanglements on the high seas. Isolationists in Congress felt reasonably confident that these measures would keep the United States out of another war.

But as the decade passed, President Roosevelt was growing increasingly skeptical.

War Breaks Out

German troops parade through Warsaw in September 1939 following their invasion of Poland. Britain and France responded to this action with declarations of war against Germany. World War II was officially underway.

On July 7, 1937, a skirmish between Chinese and Japanese troops broke out at the MARCO POLO BRIDGE near Beijing. The cause of the fracas is unknown, but the Japanese government used it as a pretext to launch a full-scale invasion of China. Hoping to deliver a quick knockout punch, the Japanese furiously bombed Chinese cities and advanced with their better-equipped army. Despite enduring heavy losses, the Chinese regrouped in the interior of their vast land and mounted an entrenched resistance.

Reports of the "RAPE OF NANKING," the sacking of the Chinese capital reached the American mainland in the summer of 1937. The brutalities prompted President Roosevelt to abandon cooperation with Congressional isolationists to pursue a more forceful approach against the Japanese.

The Munich Pact of 1938 recognized Germany's claim to the Sudetenland and Italy's claim to Ethiopia in exchange for the promise of no further aggressions. This memorial sheet depicts Neville Chamberlain and Eduardo Daladier, the leaders of Britain and France, standing opposite Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

In October 1937, he delivered his famousQUARANTINE SPEECH in Chicago. For the first time, Roosevelt advocated collective action to stop the epidemic aggression. But his hopes of igniting American sensibilities failed. Even when a Japanese plane bombed the USS PANAY on December 12, there was no cry for a response. ThePanay had been stationed in China on the Yangtze River. Japan apologized and paid an indemnity and the incident was soon forgotten, despite the loss of three American lives. Compared to the public response to the sinking of the MAINE in 1898, the American people hardly mustered a whisper.

Emboldened by western inaction, Hitler's troops marched into Austria in 1938 and annexed the country. Then Hitler set his eyes upon the SUDETENLAND, a region in western Czechoslovakia inhabited by 3.5 million Germans. In September the leaders of Britain, France, Germany, and Italy met in Munich attempting to diffuse a precarious situation.

Britain and France recognized Hitler's claim to the Sudetenland and Mussolini's conquest of Ethiopia in exchange for the promise of no future aggressions. PRIME MINISTER NEVILLE CHAMBERLAIN returned to Great Britain triumphantly proclaiming that he had achieved "peace in our time." It would be one of the most mocked statements of the 20th century.

This map of Czechoslovakia shows the fierce land-grabbing that took place in the Fall of 1938. Hungary, Germany, and Poland all managed to claim a piece as their own.

European appeasement failed six months later, as Hitler mockingly marched his troops into the rest of Czechoslovakia.

In May 1939, Roosevelt urged Congressional leaders to repeal the arms embargo of the earlier Neutrality Acts. Senators from both parties refused the request. Another bombshell crossed the Atlantic on August 24. Adolf Hitler and JOSEF STALIN agreed to put their mutual hatred aside. Germany and the Soviet Union signed a ten-yearNONAGGRESSION PACT. Hitler was now free to seize the territory Germany had lost to Poland as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. On September 1, 1939, Nazi troops crossed into Poland from the west.

Finally, on September 3, France and Great Britain declared war on Germany. World War II had begun.

The Arsenal of Democracy

Although short of planes and pilots, the British Royal Air Force managed to hold off Hitler's Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain.

War had finally come.

Two days after Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany, President Roosevelt issued a proclamation of neutrality and ordered the suspension of munitions sales to all belligerents. But Roosevelt stopped short of asking that Americans remain emotionally neutral in the European conflict. FDR knew that the only chance Britain and France would have to defeat the German Reich was to have ample supplies of weaponry. He immediately began to press Congress to repeal the ARMS EMBARGO.

The request was simple. Allow trade of MUNITIONS with belligerent nations on a "cash and carry" basis. There would be no danger to American shipping if the Allies had to carry the supplies on their own ships. Isolationists were concerned, but support for the President's initiative was strong enough. TheNEUTRALITY ACT OF 1939 ended the arms embargo and permitted the sales of munitions on a "cash and carry" basis.

Meanwhile, the European war seemed to be more talk than action. Throughout the fall and winter of 1939-40, Stalin moved Soviet troops into sovereign Eastern European states including eastern Poland, but Hitler'sWEHRMACHT was silent. Europeans nervously joked of a "phony war" as the winter drew to a close.

Suddenly on April 9, 1940, the German BLITZKRIEG moved rapidly into Denmark and Norway. As the weeks passed, the German war machine steadily advanced through the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and into northern France. Hitler arrived in France to sign the terms of French surrender. The hapless French were forced to submit to the Germans in the very same railroad car the Germans surrendered twenty-two years previously at the end of World War I. Britain was the only democracy in Europe in open opposition to Germany.

Not to be outdone by the swelling "Arsenal of Democracy," German production increased as well during World War II.

New PRIME MINISTER WINSTON CHURCHILL desperately pleaded with Roosevelt for assistance. In the summer of 1940, Hitler launched OPERATION SEA LION, an all-out assault on the British mainland. The ROYAL AIR FORCE of Britain battled the German Luftwaffe in the greatest air battle in history as Americans watched nervously.

Slowly but surely American public opinion shifted toward helping the British. The COMMITTEE TO DEFEND AMERICA BY AIDING THE ALLIES launched a propaganda campaign to mobilize the American public. Groups like the AMERICA FIRST COMMITTEE, which contained prominent Americans such as CHARLES LINDBERGH, insisted a hemispheric defense was the wisest choice for the United States to follow. A great debate was on.

Miraculously Britain held its own with Germany while America deliberated. In September 1940, the United States agreed to the transfer of 50 old destroyers to the British fleet in exchange for naval bases in the Western Hemisphere. By directly aiding the ALLIES, America could no longer hide behind the shield of neutrality. At Roosevelt's urging, Congress authorized the construction of new planes to defend America's coast. Congress also enacted the first peacetime draft in the nation's history in September 1940. The interventionist argument seemed to be prevailing, but debate continued into 1941.

Congress eventually approved the Lend-Lease Act, but not without a great deal of debate. Senator Robert Taft argued that the Act allowed the U.S. "to carry on a kind of undeclared war."

The DESTROYER DEAL was helpful, but Britain simply did not have the financial reserves to pay for all the weapons they needed. Roosevelt feared another postwar debt crisis so he hatched a new plan called Lend-Lease. Roosevelt publicly mused that if a neighbor's house is on fire, nobody sells him a hose to put it out. Common sense dictated that the hose is lent to the neighbor and returned when the fire is extinguished. The United States could simply lend Great Britain the materials it would need to fight the war. When the war was over, they would be returned. The Congress hotly argued over the proposal.SENATOR ROBERT TAFT retorted: "Lending war equipment is a good deal like lending chewing gum. You don't want it back."

In March 1941 after a great deal of controversy, Congress approved the LEND-LEASE ACT, which eventually appropriated $50 billion of aid to the Allies. Meanwhile Roosevelt began an unprecedented third term.

Neutrality was no longer a façade behind which America could hide. Hitler saw Lend-Lease as tantamount to a war declaration and ordered attacks on American ships.

Roosevelt urged Congress and Americans to take action. In his famous FOUR FREEDOM SPEECH he enumerates what the rights of any citizen of the world are and why it is important for America to lead the way:

The first is freedom of speech and expression — everywhere in the world. The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world. The third is freedom from want, which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants — everywhere in the world. The fourth is freedom from fear, which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor — anywhere in the world.

Congress still vacillated. Roosevelt met with Churchill in the summer of 1941 and agreed to the ATLANTIC CHARTER, a statement that outlined Anglo-American war aims. At this point, the United States was willing to commit almost everything to the Allied war machine — money, resources, and diplomacy.

The only thing missing was American troops.

Pearl Harbor

The USS Arizona was pounded by Japanese bombers as it rested at anchor at Pearl Harbor. The ship ultimately sank, taking the lives of 1,177 crew members.

While the international picture in Europe was growing increasingly dimmer for the United States, relations with Japan were souring as well. Japan's aggression was literally being fueled by the United States. The Japanese military machine relied heavily on imports of American steel and oil to prosecute its assault on China and French Indochina.

Placing a strict embargo on Japan would have seemed obvious, but Roosevelt feared that Japan would strike at the resource-laden Dutch East Indies to make up the difference. Beginning in late-1940, the United States grew less patient with Japanese atrocities and began to restrict trade with the Empire.

Just prior to Hitler's invasion of the Soviet Union, Japan signed a nonaggression pact with Stalin. This removed the threat of a Russian attack on Japan's new holdings. With Europe busy fighting Hitler, the United States remained the only obstacle to the establishment of a huge Japanese empire spanning East Asia.

By the end of 1940, the United States had ended shipments of scrap metal, steel, and iron ore to Japan. Simultaneously, the United States began to send military hardware to CHIANG KAI-SHEK, the nominal leader of the Chinese forces resisting Japanese takeover.

By the beginning of World War II, Japan had established a powerful navy aviation division. It was this superior air power that carried out the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Negotiations between Japan and the U.S. began in early 1941, but there was little movement. By midsummer, FDR made the fateful step of freezing all Japanese assets in the United States and ending shipments of oil to the island nation. Negotiations went nowhere. The United States was as unwilling to accept Japanese expansion and Japan was unwilling to end its conquests.

American diplomats did, however, have a hidden advantage. With the help of "MAGIC," a decoding device, the United States was able to decipher Japan's radio transmissions. Leaders in Washington knew that the deadline for diplomacy set by Japan's high command was November 25. When that date came and passed, American officials were poised for a strike. The prevailing view was that the attack would focus on British Malaya or the Dutch East Indies to replenish dwindling fuel supplies.

Unbeknown to the United States, a Japanese fleet of aircraft carriers stealthily steamed toward Hawaii.

The goals for the Japanese attack were simple. Japan did not hope to conquer the United States or even to force the abandonment of Hawaii with the attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States was too much of a threat to their newly acquired territories. With holdings in the Philippines, Guam, American Samoa, and other small islands, Japan was vulnerable to an American naval attack. A swift first strike against the bulk of the UNITED STATES PACIFIC FLEET would seriously cripple the American ability to respond. The hopes were that Japan could capture the PHILIPPINES and American island holdings before the American navy could recuperate and retaliate. An impenetrable fortress would then stretch across the entire Pacific Rim. The United States, distracted by European events, would be forced to recognize the new order in East Asia.

On the morning of December 7, 1941, approximately 100 U.S. Navy battleships, destroyers, cruisers, and support ships, were present at Pearl Harbor.

All these assumptions were wrong. As the bombs rained on PEARL HARBOR on the infamous morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, almost 3,000 Americans were killed. Six battleships were destroyed or rendered unseaworthy, and most of the ground planes were ravaged as well. Americans reacted with surprise and anger.

Most American newspaper headlines had been focusing on European events, so the Japanese attack was a true blindside. When President Roosevelt addressed the Congress the next day and asked for a declaration of war, there was only one dissenting vote in either house of Congress. Despite two decades of regret over World War I and ostrichlike isolationism, the American people plunged headfirst into a destructive conflict.