Reading: The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War

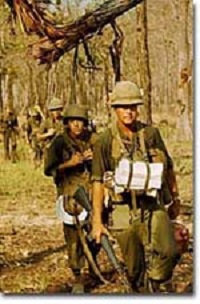

These young soldiers were members of the U.S. 1st Air Cavalry. This picture was taken in 1965, during the first military engagements between U.S. and North Vietnamese ground forces.

The VIETNAM WAR was the longest war in United States history.

Promises and commitments to the people and government of South Vietnam to keep communist forces from overtaking them reached back into the Truman Administration. Eisenhower placed military advisers and CIA operatives in Vietnam, and John F. Kennedy sent American soldiers to Vietnam. Lyndon Johnson ordered the first real combat by American troops, and Richard Nixon concluded the war.

Despite the decades of resolve, billions and billions of dollars, nearly 60,000 American lives and many more injuries, the United States failed to achieve its objectives.

One factor that influenced the failure of the United States in Vietnam was lack of public support. However, the notion that the war initially was prosecuted by the government against the wishes of the American people is false. The notion that the vast majority of American youths took to the streets to end the Vietnam War is equally false. Early initiatives by the United States under Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy received broad support.

Only two members of the United States Congress voted against granting Johnson broad authority to wage the war in Vietnam, and most Americans supported this measure as well. The antiwar movement in 1965 was small, and news of its activities was buried in the inner pages of newspapers, if there was any mention at all. Only later in the war did public opinion sour.

The enemy was hard to identify. The war was not fought between conventional army forces. The Viet Cong blended in with the native population and struck by ambush, often at night. Massive American bombing campaigns hit their targets, but failed to make the North Vietnamese concede. Promises made by American military and political leaders that the war would soon be over were broken.

And night after night, Americans turned on the news to see the bodies of their young flown home in bags. Draft injustices like college deferments surfaced, hearkening back to the similar controversies of the Civil War. The average age of the American soldier in Vietnam was nineteen. As the months of the war became years, the public became impatient.

Only a small percentage of Americans believed their government was evil or sympathized with the Viet Cong. But many began to feel it was time to cut losses. Even the iconic CBS newscaster WALTER CRONKITE questioned aloud the efficacy of pursuing the war.

President Nixon signed a ceasefire in January 1973 that formally ended the hostilities. In 1975, communist forces from the north overran the south and unified the nation. Neighboring CAMBODIA and LAOS also became communist dictatorships. At home, returning Vietnamese veterans found readjustment and even acceptance difficult. The scars of Vietnam would not heal quickly for the United States.

The legacy of bitterness divided the American citizenry and influenced foreign policy into the 21st century.

Early Involvement

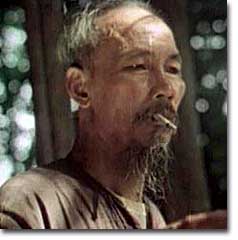

Ho Chi Minh's resistance to colonial powers in Indochina led to the formation of the Marxist liberation movement known as the Viet Minh. The United States provided financial support to France's fight against Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh from the 1940s until direct U.S. involvement.

While Americans were girding to fight the Civil War in 1860, the French were beginning a century-long imperial involvement in Indochina. The lands now known as Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia comprised INDOCHINA. The riches to be harvested in these lands proved economically enticing to the French.

After World War I, a nationalist movement formed in Vietnam led byHO CHI MINH. Ho was educated in the West, where he became a disciple of Marxist thought. Ho resented and resisted the French. When the Japanese invaded Vietnam during World War II, they displaced French rule. Ho formed a liberation movement known as the Viet Minh. Using guerrilla warfare, the VIET MINH battled the Japanese and held many key cities by 1945. Paraphrasing the Declaration of Independence, Ho proclaimed the new nation of Vietnam — a new nation Western powers refused to recognize.

France was determined to reclaim all its territories after World War II. The United States now faced an interesting dilemma. American tradition dictated sympathy for the revolutionaries over any colonial power. However, supporting the Marxist Viet Minh was unthinkable, given the new strategy of containing communism.

Domino Theory

American diplomats subscribed to the DOMINO THEORY. A communist victory in Vietnam might lead to communist victories in Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Such a scenario was unthinkable to the makers of American foreign policy.

President Truman decided to support France in its efforts to reclaim Indochina by providing money and military advisers. The United States financial commitment amounted to nearly $1 billion per year.

The French found Ho Chi Minh a formidable adversary. Between 1945 and 1954 a fierce war developed between the two sides. Slowly but surely, the Viet Minh wore down the French will to fight. On May, 8th, 1954 a large regiment of French troops was captured by the Vietnamese led by communist general VO NGUYEN GIAP at DIEN BIEN PHU.

A Nation Divided

The rest of the French troops withdrew, leaving a buffer zone separating the North and South. Negotiations to end the conflict took place in Geneva. A multinational agreement divided Vietnam at the 17th parallel. The territory north of this line would be led by Ho Chi Minh with Hanoi its capital.

The southern sector named Saigon its capital and Ngo Dinh Diem its leader. This division was meant to be temporary, with nationwide elections scheduled for 1956. Knowing that Ho Chi Minh would be a sure victor, the South made sure these elections were never held.

During the administrations of Eisenhower and Kennedy, the United States continued to supply funds, weapons, and military advisers to SOUTH VIETNAM.Ho Chi Minh turned NORTH VIETNAM into a communist dictatorship and created a new band of GUERRILLAS in the South called the Viet Cong, whose sole purpose was to overthrow the military regime in the South and reunite the nation under Ho Chi Minh.

The United States was backing an unpopular leader in NGO DINH DIEM. Diem was corrupt, showed little commitment to democratic principles, and favored Catholics to the dismay of the Buddhist majority. In November 1963, Diem was murdered in a coup with apparent CIA involvement.

Few of Ngo's successors fared any better, while Ho Chi Minh was the Vietnamese equivalent of George Washington. He had successfully won the hearts and minds of the majority of the Vietnamese people. Two weeks after the fall of Diem, Kennedy himself was felled by an assassin's bullet.

By the time Lyndon Johnson inherited the Presidency, Vietnam was a bitterly divided nation. The United States would soon too be divided on what to do in Vietnam.

Years of Escalation: 1965-68

Along with Agent Orange, the substance known as napalm was used to clear forest growth as well as inflict heavy damages upon North Vietnamese forces. Essentially gasoline in gel form, napalm was extremely flammable and resulted in devastating fires.

It was David vs. Goliath, with U.S. playing Goliath.

On August 2, 1964, gunboats of North Vietnam allegedly fired on ships of the United States Navy stationed in the GULF OF TONKIN. They had been sailing 10 miles off the coast of North Vietnam in support of the South Vietnamese navy.

When reports that further firing occurred on August 4, President Johnson quickly asked Congress to respond. With nearly unanimous consent, members of the Senate and House empowered Johnson to "take all necessary measures" to repel North Vietnamese aggression. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution gave the President a "BLANK CHECK" to wage the war in Vietnam as he saw fit. After Lyndon Johnson was elected President in his own right that November, he chose escalate the conflict.

Operation Rolling Thunder

In February 1965, the United States began a long program of sustained bombing of North Vietnamese targets known as OPERATION ROLLING THUNDER. At first only military targets were hit, but as months turned into years, civilian targets were pummeled as well.

The United States also bombed the Ho Chi Minh trail, a supply line used by the North Vietnamese to aid the VIETCONG. The trail meandered through Laos and Cambodia, so the bombing was kept secret from the Congress and the American people. More bombs rained down on Vietnam than the Allies used on the Axis powers during the whole of World War II.

Additional sorties delivered defoliating agents such as AGENT ORANGE and napalm to remove the jungle cover utilized by the Vietcong. The intense bombardment did little to deter the communists. They continued to use the Ho Chi Minh trail despite the grave risk. The burrowed underground, building 30,000 miles of tunnel networks to keep supply lines open.

Ground Troops

Often unable to see the enemy through the dense growth of Vietnam's jungles, the U.S. military sprayed a chemical herbicide known as "Agent Orange" in an attempt to destroy the trees. Currently, debate rages on whether or not exposure to this compound is responsible for disease and disability in many Vietnam veterans.

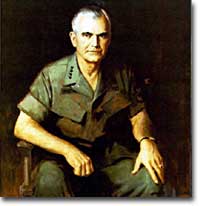

It soon became clear to GENERAL WILLIAM WESTMORELAND, the American military commander, that combat troops would be necessary to root out the enemy. Beginning in March 1965, when the first American combat troops waded ashore at Danang, the United States began "search and destroy" missions.

One of the most confounding problems faced by U.S. military personnel in Vietnam was identifying the enemy. The same Vietnamese peasant who waved hello in the daytime might be a VC guerrilla fighter by night. The United States could not indiscriminately kill South Vietnamese peasants. Any mistake resulted in a dead ally and an angrier population.

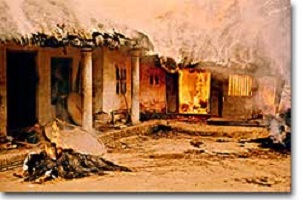

Search and destroy missions were conducted by moving into a village and inspecting for any signs of Vietcong support. If any evidence was found, the troops would conduct a "ZIPPO RAID" by torching the village to the ground and confiscating discovered munitions. Most efforts were fruitless, as the VC proved adept at covering their tracks. The enemy surrounded and confounded the Americans but direct confrontation was rare.

The media played an important part in shaping the public's opinion towards the conflict in Vietnam. Television brought the horrors of war into millions of homes, as did photos like this one of a young Vietnamese girl fleeing a napalm bombing.

By the end of 1965, there were American 189,000 troops stationed in Vietnam. At the end of the following year, that number doubled. Casualty reports steadily increased. Unlike World War II, there few major ground battles.

Most Vietnamese attacks were by ambush or night skirmishes. Many Americans died by stepping on landmines or by triggering BOOBY TRAPS. Although Vietnamese body counts were higher, Americans were dying at rate of approximately 100 per week through 1967. By the end of that year there were nearly 500,000 American combat troops stationed in Vietnam.

General Westmoreland promised a settlement soon, but the end was not in sight.

The Tet Offensive

The fighting that made up the Tet Offensive lasted for several days in some South Vietnamese cities. This map shows the route taken by North Vietnamese troops.

During the BUDDHIST holiday of TET, over 80,000 Vietcong troops emerged from their tunnels and attacked nearly every major metropolitan center in South Vietnam. Surprise strikes were made at the American base at DANANG, and even the seemingly impenetrable American embassy in SAIGON was attacked.

During the weeks that followed, the South Vietnamese army and U.S. ground forces recaptured all of the lost territory, inflicting twice as many casualties on the Vietcong as suffered by the Americans.

The showdown was a military victory for the United States, but American morale suffered an insurmountable blow.

Doves Outnumber Hawks

When Operation Rolling Thunder began in 1965, only 15 percent of the American public opposed the war effort in Vietnam. As late as January 1968, only a few weeks before Tet, only 28 percent of the American public labeled themselves "doves." But by April 1968, six weeks after the TET OFFENSIVE,"DOVES" outnumbered "HAWKS" 42 to 41 percent.

Only 28% of the American people were satisfied with President Johnson's handling of the war. The Tet Offensive convinced many Americans that government statements about the war being nearly over were false. After three years of intense bombing, billions of dollars and 500,000 troops, the VC proved themselves capable of attacking anywhere they chose. The message was simple: this war was not almost over. The end was nowhere in sight.

Sagging U.S. Troop Morale

Declining public support brought declining troop morale. Many soldiers questioned the wisdom of American involvement. Soldiers indulged in alcohol, marijuana, and even heroin to escape their daily horrors. Incidents of "FRAGGING," or the murder of officers by their own troops increased in the years that followed Tet. Soldiers who completed their yearlong tour of duty often found hostile receptions upon returning to the states.

Following the Tet Offensive, General William Westmoreland called for an additional 200,000 troops to help break the resolve of the Vietcong. But President Lyndon B. Johnson's rejection of the proposal showed that America's commitment to the war in Vietnam was waning.

After Tet, General Westmoreland requested an additional 200,000 troops to put added pressure on the Vietcong. His request was denied. President Johnson knew that activating that many reserves, bringing the total American commitment to nearly three quarters of a million soldiers was not politically tenable.

The North Vietnamese sensed the crumbling of American resolve. They knew that the longer the war raged, the more antiwar sentiment in America would grow. They gambled that the American people would demand troop withdrawals before the military met its objectives.

For the next five years they pretended to negotiate with United States, making proposals they knew would be rejected. With each passing day, the number of "hawks" in America decreased. Only a small percentage of Americans objected to the war on moral grounds, but a growing majority saw the war as an effort whose price of victory was way too high.

The Antiwar Movement

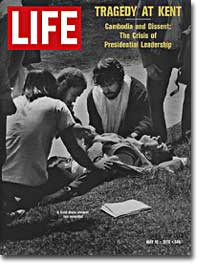

Following Richard Nixon's announcement that U.S. troops would be sent into Cambodia, protests began on college campuses throughout the nation. At Kent State University in Ohio, four demonstrators were killed by shots fired by the Ohio National Guard.

Of all the lessons learned from Vietnam, one rings louder than all the rest — it is impossible to win a long, protracted war without popular support.

When the war in Vietnam began, many Americans believed that defending South Vietnam from communist aggression was in the national interest. Communism was threatening free governments across the globe. Any sign of non-intervention from the United States might encourage revolutions elsewhere.

As the war dragged on, more and more Americans grew weary of mounting casualties and escalating costs. The small antiwar movement grew into an unstoppable force, pressuring American leaders to reconsider its commitment.

PEACE MOVEMENT leaders opposed the war on moral and economic grounds. The North Vietnamese, they argued, were fighting a patriotic war to rid themselves of foreign aggressors. Innocent Vietnamese peasants were being killed in the crossfire. American planes wrought environmental damage by dropping their defoliating chemicals.

Ho Chi Minh was the most popular leader in all of Vietnam, and the United States was supporting an undemocratic, corrupt military regime. Young American soldiers were suffering and dying. Their economic arguments were less complex, but as critical of the war effort. Military spending simply took money away from Great Society social programs such as welfare, housing, and urban renewal.

The Draft

The draft was another major source of resentment among college students. The age of the average American soldier serving in Vietnam was 19, seven years younger than its World War II counterpart. Students observed that young Americans were legally old enough to fight and die, but were not permitted to vote or drink alcohol. Such criticism led to the 26TH AMENDMENT, which granted suffrage to 18-year-olds.

Slogans like "How Many More?," "I'm a Viet Nam Dropout" and "Ship the GI's Home Now!" graced the buttons, flags and banners of the anti-war movement.

Because DRAFT DEFERMENTS were granted to college students, the less affluent and less educated made up a disproportionate percentage of combat troops. Once drafted, Americans with higher levels of education were often given military office jobs. About 80 percent of American ground troops in Vietnam came from the lower classes. Latino and African American males were assigned to combat more regularly than drafted white Americans.

Antiwar demonstrations were few at first, with active participants numbering in the low thousands when Congress passed theTONKIN GULF RESOLUTION. Events in Southeast Asia and at home caused those numbers to grow as the years passed. As the Johnson Administration escalated the commitment, the peace movement grew. Television changed many minds. Millions of Americans watched body bags leave the Asian rice paddies every night in their living rooms.

Give Peace a Chance

The late 1960s became increasingly radical as the activists felt their demands were ignored. Peaceful demonstrations turned violent. When the police arrived to arrest protesters, the crowds often retaliated. Students occupied buildings across college campuses forcing many schools to cancel classes. Roads were blocked and ROTC buildings were burned. Doves clashed with police and the National Guard in August 1968, when antiwar demonstrators flocked to the Democratic National Convention in Chicago to prevent the nomination of a prowar candidate.

Massive gatherings of anti-war demonstrators helped bring attention to the public resentment of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The confrontation seen above took place at the Pentagon in 1967.

Despite the growing antiwar movement, a silent majority of Americans still supported the Vietnam effort. Many admitted that involvement was a mistake, but military defeat was unthinkable.

When Richard Nixon was inaugurated in January 1969, the nation was bitterly divided over what course of action to follow next.

Years of Withdrawal

The unspeakable horror of the 1968 My Lai massacre was not revealed to the American public until investigative journalist Seymour Hersh published his findings in November, 1969. According to troops who either witnessed or took part in the massacre, orders had been given "to destroy My Lai and everything in it." Over 300 civilians were killed and the village itself was burned to the ground.

President Nixon had a plan to end American involvement in Vietnam.

By the time he entered the White House in 1969, he knew the American war effort was failing. Greater military power may have brought a favorable outcome, but there were no guarantees. And the American people were less and less willing to support any sort of escalation with each passing day.

Immediate American withdrawal would amount to a defeat of the noncommunist South Vietnamese allies. Nixon announced a plan later known as VIETNAMIZATION. The United States would gradually withdraw troops from Southeast Asia as American military personnel turned more and more of the fighting over to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. In theory, as the South Vietnamese became more able to defend themselves, United States soldiers could go home without a communist takeover of Saigon.

Troop withdrawals did little to placate the antiwar movement. Demonstrators wanted an immediate and complete departure. Events in Vietnam and at home gave greater strength to the protesters.

In the spring of 1970, President Nixon announced a temporary invasion of neighboring Cambodia. Although Cambodia was technically neutral, the Ho Chi Minh trail stretched through its territory. Nixon ordered the Viet Cong bases located along the trail to be bombed.

Kent State and MY LAI MASSACRES

Peace advocates were enraged. They claimed that Nixon was expanding the war, not reducing it as promised. Protests were mounted across America.

At KENT STATE UNIVERSITY, students rioted in protest. The burned down the ROTC building located on campus, and destroyed local property. The governor of Ohio sent the National Guard to maintain order. A state of high tension and confusion hung between the Guard and the students. Several soldiers fired their rifles, leading to deaths of four students and the wounding of several others. This became known as the Kent State massacre.

This B-52 bomber in the background of this photo — downed during bombing in 1968 — sits in a small pond in Hanoi. Busy markets surround the fallen plane and the site has become a popular tourist destination.

The following year the American public learned about the My Lai massacre. In 1968, American soldiers opened fire on several hundred women and children in the tiny hamlet of My Lai. How could this happen? It was not unusual for Viet Cong guerilla activity to be initiated from small villages. Further, U.S. troops were tired, scared, and confused.

At first the Lieutenant who had given the order, WILLIAM L. CALLEY, JR., was declared guilty of murder, but the ruling was later overturned. Moral outrage swept through the antiwar movement. They cited My Lai as an example of how American soldiers were killing innocent peasants.

The Pentagon Papers

In 1971, the New York Times published excerpts from the PENTAGON PAPERS, a top-secret overview of the history of government involvement in Vietnam. A participant in the study named DANIEL ELLSBERG believed the American public needed to know some of the secrets, so he leaked information to the press. The Pentagon Papers revealed a high-level deception of the American public by the Johnson Administration.

The North Vietnamese Army captured Saigon in April, 1975, and renamed the capital Ho Chi Minh City. It was at this time that the last remaining American personnel in Vietnam were forced to flee.

Many statements released about the military situation in Vietnam were simply untrue, including the possibility that even the bombing of American naval boats in the Gulf of Tonkin might never have happened. A growing credibility gap between the truth and what the government said was true caused many Americans to grow even more cynical about the war.

By December 1972, Nixon decided to escalate the bombing of North Vietnamese cities, including Hanoi. He hoped this initiative would push North Vietnam to the peace table. In January 1973, a ceasefire was reached, and the remaining American combat troops were withdrawn. Nixon called the agreement "peace with honor," but he knew the South Vietnamese Army would have difficulty maintaining control.

The North soon attacked the South and in April 1975 they captured Saigon. Vietnam was united into one communist nation. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City. Cambodia and Laos soon followed with communist regimes of their own. The United States was finally out of Vietnam. But every single one of its political objectives for the region met with failure.

Over 55,000 Americans perished fighting the Vietnam War.