Reading: Politics from Camelot to Watergate

Politics from Camelot to Watergate

John F. Kennedy's youthful good looks helped him win the White House in 1960 and usher in an era of American politics remembered as "Camelot." The dream turned to a nightmare in 1963 when Kennedy was cut down by an assassin's bullet.

When John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon in 1960, the United States was at the apex of its postwar optimism. The 1950s economy raised the American standard of living to a level second to none. Although communism was a threat, the rebuilt nations of Western Europe proved to be solid Cold War allies.

The Soviet Union had the technology to send a nuclear missile across the North Pole, but the United States maintained a superiority that could obliterate any nation who dared such an attack. Across the world, newly independent nations looked to the United States for assistance and guidance. Few Americans would have believed that by the end of the decade, the nation would be weakened abroad and divided against itself.

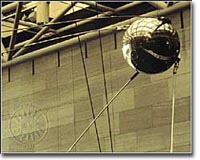

Launched by the Soviet Union in 1957, Sputnik was the first artificial satellite to successfully orbit the Earth. It was also the impetus for the formation of the National Air and Space Administration — or NASA — in the United States.

Kennedy embodied that early ebullience. The youthful president and his wife drew parallels to the magical time of King Arthur and Camelot. His New Frontier program asked the nation's talented and fortunate to work to eliminate poverty and injustice at home, while projecting confidence overseas. Although Congress blocked many of his programs, his confidence was contagious, and the shock of his untimely death was nothing less than devastating.

Upon the assassination of John F. Kennedy, then Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson set out to complete the work that Kennedy had started. However, Johnson's vision of a "Great Society" was stymied by America's involvement in Vietnam.

Lyndon Johnson hoped to complete Kennedy's work. His Great Society plan declared a "war on poverty" that produced a glut of legislation unseen since the days of Franklin Roosevelt's Hundred Days. Welfare benefits were increased, health care costs were defrayed, and funds were allotted for cleaning the air and water, rebuilding cities, and subsidizing the arts and humanities.

A Civil Rights Act ended legal discrimination in public accommodations with regard to race.

Unfortunately for Johnson, the domestic minded president became mired in a foreign imbroglio — the war in Southeast Asia. Vietnam would taint his legislative successes and end the possibility of a second Johnson term.

By 1968, the zeal for domestic reform was squelched by an increasingly popular war. Families and friends across America were divided by the conflict. Assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy only fanned the flames, and by the end of the decade most Americans were weary of war, rioting, and political crusades — Americans sought a return to normalcy.

The Election of 1960

Coming into the first televised Presidential debate, John F. Kennedy had spent time relaxing in Florida while Richard Nixon maintained a hectic campaign schedule. As a result, Kennedy appeared tan and relaxed during the debate while Nixon seemed a bit worn down. Radio listeners proclaimed Nixon the better debater, while those who watched on television made Kennedy their choice.

It was one of the closest elections in American history.

The Republican insider was Richard Nixon of California, relatively young but experienced as the nation's Vice-President for 8 years under Dwight Eisenhower. The Democratic newcomer was JOHN F. KENNEDY, senator from Massachusetts, who at the age of 43 could become the youngest person ever to be elected President. Regardless of the outcome, the United States would for the first time have a leader born in the 20th century.

Age was not the only factor in the election. Kennedy was also Roman Catholic, and no Catholic had ever been elected President before. AL SMITH, a Catholic, suffered a crushing defeat to HERBERT HOOVER in 1928. This raised serious questions about the electability of a Catholic candidate, particularly in the Bible Belt South. Questions were raised about Kennedy's ability to place national interests above the wishes of his Pope.

The Presidential election of 1960 was one of the closest in American history. John F. Kennedy won the popular vote by a slim margin of approximately 100,000 votes. Richard Nixon won more individual states than Kennedy, but it was Kennedy who prevailed by winning key states with many electoral votes.

To mollify these concerns, Kennedy addressed a group of Protestant ministers. He pledged a solid commitment to separation of church and state. Despite his assurances, his faith cost him an estimated 1.5 million votes in November 1960. Nixon decided to leave religious issues out of the campaign and hammer the perception that Kennedy was too inexperienced to sit in the Oval Office.

Nixon stressed his steadfast commitment to fighting communism. He had made a name for himself as a staunch red-baiter in the post-war era, leading the charge against alleged spy ALGER HISS. Nixon emphasized the importance of his 8 years as Vice-President. The Soviet Union and China were always pressing, and America could ill afford a President who had to learn on the job.

Kennedy stressed his character, assisted by those in the press who reported stories about his World War II heroism. While he was serving in the South Pacific aboard the PT109, a Japanese destroyer rammed his ship and snapped it in two. Kennedy rescued several of his crewmates from certain death. Then he swam from island to island until he found a group of friendly natives who delivered a distress message Kennedy had carved into a coconut to an American naval base. Courage and character became the major themes of Kennedy's campaign.

Although both candidates were seen as moderates on nearly every policy issue of the time, each hailed from different backgrounds. Kennedy was from a wealthy background and graduated from Harvard University. Nixon painted himself the average American, growing up poor in California, and working his way through Whittier College.

The combination of New Englander John F. Kennedy and Texan Lyndon B. Johnson created what some called a "Boston-Austin connection" that helped balance the 1960 Democratic ticket geographically.

In an attempt to broaden his base, Kennedy named one of his opponents for the Democratic nomination his Vice-President. Lyndon Johnson was older and much more experienced in the Senate. Johnson was from Texas, an obvious attempt by Kennedy to shore up his potential weaknesses in the South. Nixon named Massachusetts SENATOR HENRY CABOT LODGE as his running mate to attack Kennedy in his region of greatest strength.

In such a close contest, every event matters. Many analysts suggest that the decisive battle in the campaign was waged during the televised Presidential debates. Kennedy arrived for the debates well-tanned and well-rested from Florida, while Nixon was recovering from a knee injury he suffered in a tiresome whistle-stop campaign. The Democrat was extremely telegenic and comfortable before the camera. The Republican was nervous, sweated profusely under the hot lights, and could not seem to find a makeup artist that could hide his five o'clock shadow.

Radio listeners of the first debate narrowly awarded Nixon a victory, while the larger television audience believed Kennedy won by a wide margin. When the votes were tallied in November, Kennedy earned 49.7% of the popular vote to Nixon's 49.5%. Kennedy polled only about 100,000 more votes than Nixon out of over 68 million votes cast. The electoral college awarded the election to Kennedy by a 303-219 margin, despite Nixon winning more states than Kennedy.

Kennedy's New Frontier

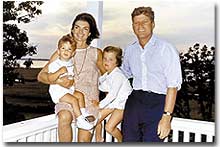

John F. Kennedy's youthful looks, cheerful family and charming demeanor captured the American imagination like few Presidents had ever done. Here, Kennedy poses with his wife Jacqueline and their two children John and Caroline.

They called it Camelot.

Like King Arthur and Guinevere, a dynamic young leader and his beautiful bride led the nation. The White House was their home, America their kingdom. They were John F. andJACQUELINE KENNEDY.

After squeaking by Richard Nixon in the election of 1960, John F. Kennedy set forth new challenges for the United States. In his inauguration speech, he challenged his fellow Americans to "Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country."

Earth's place in the universe was seen from a dramatic new perspective when American astronauts reached the Moon in the late 1960s. While the first landing on the Moon's surface would not take place until 1969, this photograph of an "earthrise" was taken during the 1968 Apollo 8 data collection mission.

Proclaiming that the "torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans," Kennedy, young and good-looking, boldly and proudly assumed office with a bravado. Many Americans responded to his call by joining the newly formed Peace Corps or volunteering in America to work toward social justice. The nation was united, positive, and forward-looking. No frontier was too distant.

The newest frontier was space. In 1957, the Soviet Union shocked Americans by launching SPUTNIK, the first satellite to be placed in orbit. Congress responded by creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) under President Eisenhower. When Kennedy took office, the United Space fell farther behind. The Soviets had already placed a dog in space ("mutnik," to the press), and in Kennedy's first year, Soviet cosmonaut YURI GAGARINbecame the first human being to orbit the earth.

John F. Kennedy backed the civil rights movement and supported James Meredith's enrollment in the University of Mississippi. Fear that violent opposition to his attendance could erupt at any moment led to Meredith's having to be escorted to class by U.S. marshals.

Kennedy challenged the American people and government to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. Congress responded enthusiastically by appropriating billions of dollars for the effort. During Kennedy's administration ALAN SHEPHERDbecame the first American to enter space, and JOHN GLENN became the first American to orbit the earth. In 1969, many thought of President Kennedy's challenge when Neil Armstrong became the first human being to set foot on the moon.

Domestically, Kennedy continued in the tradition of liberal Democrats Roosevelt and Truman to some extent. He signed legislation raising the minimum wage and increasing Social Security benefits. He raised money for research into mental illness and allocated funds to develop impoverished rural areas. He showed approval for the civil rights movement by supporting James Meredith's attempt to enroll at the University of Mississippi and by ordering his Attorney General, brother Robert Kennedy, to protect the freedom riders in the South.

Weighing in at just 184 pounds, Sputnik was the world's first man-made satellite. Its launch by Russia in 1957 resulted in the almost immediate formation of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in the United States. The "space race" was on.

However, most of Kennedy's more revolutionary proposals languished in the conservative Congress. He wished to protect millions of acres of wilderness lands from developments, but the Congress refused. His efforts to provide federal funds to elementary and secondary schools were denied. His Medicare plan to provide health insurance for the nation's elderly failed to achieve the necessary support. Congress was dominated by a coalition of Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats who refused to expand the New Deal any further.

In his abbreviated Presidency, Kennedy failed to accomplish all he wanted domestically. But the ideas and proposals he supported survived his assassination. Medicare, federal support for education, and wilderness protection all became part of Lyndon Johnson's Great Society.

Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated Kennedy in November, 1963. His death provided a popular mandate for these important programs. In the tumultuous years that followed, many yearned for the happy Kennedy years — a return to Camelot.

Kennedy's Global Challenges

Cuba became a hot spot for the Kennedy administration for two reasons during the early 1960s. The failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 was an attempt to incite a popular uprising against Fidel Castro. One year later, the Cuban Missile Crisis saw Kennedy demand an end to Russia's plan to store nuclear arms just 90 miles form U.S. soil.

The Cold War raged on in the 1960s.

President Kennedy faced a confident Soviet Union and a sleeping giant in the PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA. Fears of communist expansion plagued American foreign policy in places as distant as Vietnam and as close as Cuba.

Like his predecessors, Kennedy made containment his chief foreign policy goal. Abandoning Dwight Eisenhower's heavy reliance on nuclear deterrence, Kennedy expanded defense spending. The United States needed a "FLEXIBLE RESPONSE" capability.

To Kennedy, this meant a variety of military options depending upon the specific conditions. Conventional forces were upgraded. Included in this program was the establishment of special forces units similar to the Green Berets. Despite the expense, Kennedy believed communism was a menace that required maximal preparation.

One of Kennedy's most popular foreign policy initiatives was the PEACE CORPS. Led by SARGENT SHRIVER, this program allowed Americans to volunteer two years of service to a developing nation. Applicants would be placed based upon their particular skill sets. English teachers would be placed where the learning of the language was needed. Entrepreneurs trained local merchants how to maximize profits. Doctors and nurses were needed anywhere.

Kennedy thought the program was a win-win proposition. Third World nations received much needed assistance. The United States promoted goodwill around the world. Countries that received Peace Corps volunteers might be less likely to submit to a communist revolution. American participants obtained experiences that shaped well-rounded, worldly citizens.

John F. Kennedy's stirring address to the people of West Berlin in 1963 illustrated that the U.S. was committed to working for freedom throughout the region and the world. Kennedy ended his speech by stating: "Ich bin ein Berliner" (I am a citizen of Berlin).

Relations with Latin America had gone sour since Franklin Roosevelt's Good Neighbor Policy. Latin American nations complained bitterly about United States support of dictatorial military regimes. They pointed out that no large Marshall Plan was designed for Latin America. In that spirit, Kennedy proposed the Alliance for Progress program. Development funds were granted to nations of the Western Hemisphere who were dedicated to fighting communism. After Kennedy's death, funds for the Alliance for Progress were largely diverted to Vietnam, however.

In 1961, the citizens of West Berlin felt completely isolated when the Soviet Union built the Berlin Wall around the city. Kennedy visited West Berlin in the summer of 1963 to allay their fears. In an attempt to show solidarity between West Berlin and the United States, Kennedy ended his rousing speech with the infamous words: "ICH BIN EIN BERLINER." In essence, Kennedy was saying, "I am a citizen of West Berlin." The visit and the speech endeared him to the people of West Berlin and all of Western Europe.

Kennedy's greatest foreign policy failure and greatest foreign policy success both involved one nation — Cuba. In 1961, CIA-trained Cuban exiles landed in Cuba at the BAY OF PIGS, hoping to ignite a popular uprising that would oust Fidel Castro from power. When the revolution failed to occur, Castro's troops moved in. The exiles believed air support would come from the United States, but Kennedy refused. Many of the rebels were shot, and the rest were arrested. The incident was an embarrassment to the United States and a great victory for Fidel Castro.

In October 1962, the United States learned that the Soviet Union was about to deploy nuclear missiles in Cuba. Kennedy found this unacceptable. He ordered a NAVAL "QUARANTINE" OF CUBA and ordered Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to turn his missile-carrying boats back to the USSR. Any Soviet attempt to penetrate the American blockade would be met with an immediate military response. The world watched this dangerous game of nuclear chicken unfold. Finally, Khrushchev acceded to Kennedy's demands, and the world remained safe from global confrontation.

The CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS marked the closest the United States and the Soviet Union came to direct confrontation in the entire Cold War.

Kennedy Assassination

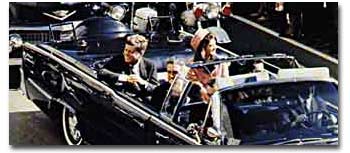

November 22, 1963, was a sunny day in Dallas, Texas, and for this reason the convertible Presidential limousine went through the afternoon parade with the top down. The President and his wife are seated in the back of the car, while Texas governor John Connally is seated directly in front of the President.

Ask any American who was over the age of 8 in 1963 the question: "Where were you when President Kennedy was shot?" and a complete detailed story is likely to follow.

On November 22, 1963, a wave of shock and grief swept the United States. While visiting Dallas, President Kennedy was killed by an assassin's bullet. Millions of Americans had indelible images burned into their memories. The bloodstained dress of Jacqueline Kennedy, a mournful Vice-President Johnson swearing the Presidential oath of office, and dozens and dozens of unanswered questions.

Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, was the site of the assassination. The large brick building directly in the center of this photo is the Texas School Book Depository, from where Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly shot President Kennedy. To the left is the "grassy knoll" where many conspiracy theorists believe a different gunman assassinated Kennedy.

President Kennedy was scheduled to speak at a luncheon in Dallas on November 22. The weather was bright and clear, and the President wished to wave to the crowds as his motorcade moved from the airport through the city. A protective covering was not placed over his convertible limousine.

As the procession moved through DEALEY PLAZA, gunshots tore through the midday air. Within minutes President Kennedy was dead, and JOHN CONNALLY, the Texas governor was badly wounded. Kennedy was rushed to the hospital, but to no avail. The news rang out through the nation. Businesses and schools closed so grief-stricken Americans could watch the unfolding events.

LEE HARVEY OSWALD was arrested for the murder. Oswald was an avowed communist who spent three years living in the Soviet Union. He allegedly shot the President from a window in the TEXAS SCHOOL BOOK DEPOSITORY in Dealey Plaza. Two days later, while Oswald was being transferred between prison facilities, a nightclub owner named JACK RUBY stepped out of the crowd and fired a bullet into Oswald at point blank range killing the prisoner. Oswald's murder was captured on live television.

Following John F. Kennedy's assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson assumed the Presidency of the United States. With the slain President's wife Jaqueline looking on mournfully, Johnson took the Oath of Office while on board the Presidential airplane, Air Force One.

Oswald's death left many unanswered, searing questions. Among them, "Did Oswald actually assassinate Kennedy?" "Did he act alone?"

A committee headed by Chief JusticeEARL WARREN studied the events surrounding the assassination and declared that Oswald was Kennedy's killer — and that he acted alone.

Critics of the Warren Commission cited irregularities in the findings. Questions surrounded the ability of any sharpshooter to fire the number of bullets Oswald supposedly fired, from such a great distance, with any degree of accuracy. Witnesses testified that shots were fired from another direction at the President — the infamous GRASSY KNOLL — suggesting the presence of a second shooter.

One theory suggests the possibility of a killer firing from a sewer grate along the road. Conspiracy talk flourished — and continues to flourish. Groups as diverse as the Cubans, the Russians, the CIA, and organized crime have been rumored Oswald cohorts.

Flaws in Kennedy's autopsy report suggest the possibility of a cover-up. The President's brain, a very important piece of forensic evidence, simply disappeared.

After years of study, no conclusive evidence has been presented to disprove the findings of the Warren Commission, but the same questions remain.

- Did Oswald kill Kennedy?

- Did he act alone?

Lyndon Johnson's "Great Society"

This 1968 political cartoon captures the struggle of Lyndon B. Johnson's time as President. While Johnson dreamed of a "Great Society," his presidency was haunted by the specter of Vietnam. Much of the funding he hoped to spend on social reforms went towards war in southeast Asia.

Lyndon Baines Johnson moved quickly to establish himself in the office of the Presidency. Despite his conservative voting record in the Senate, Johnson soon reacquainted himself with his liberal roots. LBJ sponsored the largest reform agenda since Roosevelt's New Deal.

The aftershock of Kennedy's assassination provided a climate for Johnson to complete the unfinished work of JFK's New Frontier. He had eleven months before the election of 1964 to prove to American voters that he deserved a chance to be President in his own right.

Two very important pieces of legislation were passed. First, the Civil Rights Bill that JFK promised to sign was passed into law. The Civil Rights Act banned discrimination based on race and gender in employment and ending segregation in all public facilities.

Republican Barry Goldwater attempted to unseat Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 election but was soundly defeated. This bumper sticker combines the chemical symbols for "gold" (Au) and "water" (H20) to create a whimsical and memorable campaign slogan.

Johnson also signed the omnibus ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITY ACT OF 1964. The law created the Office of Economic Opportunity aimed at attacking the roots of American poverty. A Job Corps was established to provide valuable vocational training.

Head Start, a preschool program designed to help disadvantaged students arrive at kindergarten ready to learn was put into place. The VOLUNTEERS IN SERVICE TO AMERICA (VISTA) was set up as a domestic Peace Corps. Schools in impoverished American regions would now receive volunteer teaching attention. Federal funds were sent to struggling communities to attack unemployment and illiteracy.

As he campaigned in 1964, Johnson declared a "war on poverty." He challenged Americans to build a "Great Society" that eliminated the troubles of the poor. Johnson won a decisive victory over his archconservative Republican opponent Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

American liberalism was at high tide under President Johnson.

- The Wilderness Protection Act saved 9.1 million acres of forestland from industrial development.

- The Elementary and Secondary Education Act provided major funding for American public schools.

- The Voting Rights Act banned literacy tests and other discriminatory methods of denying suffrage to African Americans.

- Medicare was created to offset the costs of health care for the nation's elderly.

- The National Endowment for the Arts and Humanities used public money to fund artists and galleries.

- The Immigration Act ended discriminatory quotas based on ethnic origin.

- An Omnibus Housing Act provided funds to construct low-income housing.

- Congress tightened pollution controls with stronger Air and Water Quality Acts.

- Standards were raised for safety in consumer products.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was part of Lyndon B. Johnson's "Great Society" reform package — the largest social improvement agenda by a President since FDR's "New Deal." Here, Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act into law before a large audience at the White House.

Johnson was an accomplished legislator and used his connections in Congress and forceful personality to pass his agenda.

By 1966, Johnson was pleased with the progress he had made. But soon events in Southeast Asia began to overshadow his domestic achievements. Funds he had envisioned to fight his war on poverty were now diverted to the war in Vietnam. He found himself maligned by conservatives for his domestic policies and by liberals for his hawkish stance on Vietnam.

By 1968, his hopes of leaving a legacy of domestic reform were in serious jeopardy.

1968: Year of Unraveling

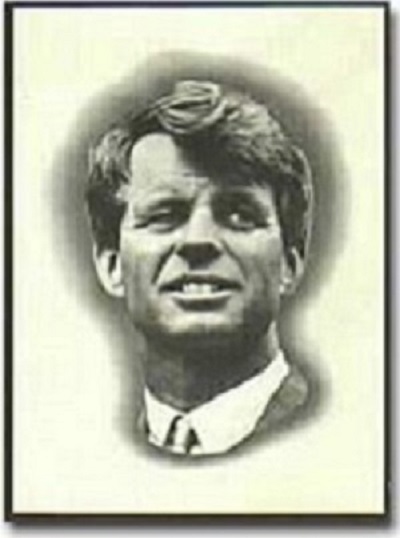

Just as Robert F. Kennedy's campaign for the White House was gaining steam he was assassinated after delivering his California primary victory speech. Fresh on the heels of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination just months before, the nation once again mourned the loss of a leader committed to civil rights. The card seen above was distributed at Kennedy's funeral.

The turbulent 1960s reached a boiling point in 1968.

When the year began, President Johnson hoped to win the war in Vietnam and then cruise to a second term to finish building his Great Society. But events began to spiral out of his control.

In February, the Tet Offensive in Vietnam brought a shift in American public opinion toward the war and low approval ratings for the President. Sensing vulnerability, EUGENE MCCARTHY challenged Johnson for his own party's nomination. When the Democratic primary votes were tallied in New Hampshire, McCarthy scored a remarkable 42 percent of the vote against an incumbent President. Johnson knew that in addition to fighting a bitter campaign against the Republicans he would have to fight to win support of the Democrats as well. His hopes darkened when Robert Kennedy entered the race in mid-March.

On March 31, 1968, Johnson surprised the nation by announcing he would not seek a second term. His Vice-PresidentHUBERT HUMPHREY entered the election to carry out Johnson's programs.

Feverish political turmoil bloomed in the spring of '68. Humphrey was popular among party elites who chose delegates in many states. But Kennedy was mounting an impressive campaign among the people. His effort touched an emotional nerve in America — the desire to return to the Camelot days of his brother. Kennedy received much support from the poorer classes and from African Americans who believed Kennedy would continue the struggle for civil rights. Both Kennedy and McCarthy were critical of Humphrey's hawkish stance on Vietnam.

The assassination of Robert F. Kennedy virtually assured Vice-President Hubert Humphrey the Democratic nomination in 1968. When the party met for their convention in Chicago, thousands of anti-war protesters converged on the city and clashed with police who had been ordered by Chicago Mayor Richard Daley to take a tough stance with the demonstrators.

On April 4, Martin Luther King's assassination led to another wave of grief. Then waves of rioting swept America. Two months later, shortly after Robert Kennedy spoke to a crowd cheering his sweep in the California primary, an assassin named SIRHAN SIRHAN ended Kennedy's life. The nation was numb.

All eyes were focused on the Democratic Convention in Chicago that August. With Kennedy out of the race, the nomination of Hubert Humphrey was all but certain. Antiwar protesters flocked to Chicago to prevent the inevitable Humphrey nomination, or at least to pressure the party into softening its stance on Vietnam.

Mayor RICHARD DALEY ordered the Chicago police to take a tough stance with the demonstrators. As the crowds chanted "The whole world is watching," the police bloodied the activists with clubs and released tear gas into the streets. The party nominated Humphrey, but the nation began to sensed that the Democrats were a party of disorder.

Lyndon B. Johnson's popularity had plummeted because of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. In addition, members of his own party were challenging him for the nomination. In March 1968, he made the stunning announcement that he would not seek another term in office.

The Republicans had a comparatively smooth campaign, nominating Richard Nixon as their candidate. Nixon spoke for the "Silent Majority" of Americans who supported the effort in Vietnam and demanded law and order. AlabamaGOVERNOR GEORGE WALLACE ran on the American Independent Party ticket. Campaigning for "segregation now, segregation forever" Wallace appealed to many white voters in the South. His running mate, CURTIS LEMAY, suggested that the United States bomb Vietnam "back to the Stone Age."

When the votes were tallied in November, Nixon cruised to an electoral voteLANDSLIDE while winning only 43.4 percent of the popular vote.

Triangular Diplomacy: U.S., USSR, and China

After his takeover in 1949, Mao Zedong's China went unrecognized for years by the United States. China was also barred from the United Nations by an American veto. Instead, the U.S. supported the Chinese Nationalist government in Taiwan.

Unlike his predecessor, RICHARD NIXON longed to be known for his expertise in FOREIGN POLICY. Although occupied with the Vietnam War, Nixon also initiated several new trends in American diplomatic relations. Nixon contended that the communist world consisted of two rival powers — the Soviet Union and China. Given the long history of animosity between those two nations, Nixon and his adviserHENRY KISSINGER, decided to exploit that rivalry to win advantages for the United States. That policy became known as triangular diplomacy.

As part of the Cold War's temporary thaw during the 1970s, Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev agreed to import American wheat into the Soviet Union. The two countries would also agree to a joint space exploration program dubbed Apollo-Soyuz.

The United States had much to offer China. Since Mao Zedong's takeover in 1949, the United States had refused recognition to the communist government. Instead, the Americans pledged support to the Chinese Nationalist government in Taiwan. China was blocked from admission to the United Nations by the American veto, and Taiwan held China's seat on the Security Council.

In June 1971 Kissinger traveled secretly to China to make preparations for a Presidential visit. After Kissinger's return, Nixon surprised everyone by announcing that he would travel to China and meet with Mao Zedong. In February 1972, Nixon toured the Great Wall and drank toasts with Chinese leaders. Soon after, the United States dropped its opposition to Chinese entry in the United Nations and groundwork was laid for the eventual establishment of diplomatic relations.

As President Nixon's national security adviser, Henry Kissinger made a secret trip to arrange the first-ever Presidential visit to China in 1972. He would become Nixon's secretary of state the next year.

As expected, this maneuver caused concern in the Soviet Union. Nixon hoped to establish aDÉTENTE, or an easing of tensions, with the USSR. In May 1972, Nixon made an equally significant trip to Moscow to support a nuclear arms agreement. The product of this visit was the STRATEGIC ARMS LIMITATION TREATY (SALT I). The United States and the Soviet Union pledged to limit the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles each side would build, and to prevent the development of anti-ballistic missile systems.

Nixon and his Soviet counterpart, LEONID BREZHNEV also agreed to a trade deal involving American wheat being shipped to the USSR. The two nations entered into a joint venture in space exploration known as APOLLO-SOYUZ.

Arguably, Nixon may have been the only president who could have accomplished this arrangement. Anticommunism was raging in the United States. Americans would view with great suspicion any attempts to make peace with either the Soviet Union or China. No one would challenge Nixon's anticommunist credentials, given his reputation as a staunch red-baiter in his early career. His overtures were chiefly accepted by the American public. Although the Cold War still burned hotly across the globe, the efforts of Nixon and Kissinger led to a temporary thaw.