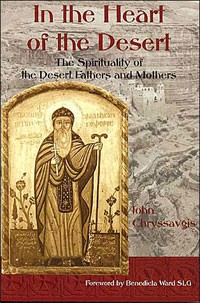

Reading: Unit 11 Lecture Transcripts & Illustrations

Unit 11 Lecture 1

This lecture is adapted from an interview in Christian History magazine. It addresses some of the background issues that influenced the group we know as the desert fathers.

The group we know as the desert fathers chose to work out their spirituality in the desert. The reason they sought God there was they knew that God was most easily found in a place without distractions. Secondly, the desert was, for them, a marvelous laboratory for dealing with their own self. That was their other major spiritual project. It reminds us today of the definition of true religion from the Reformer John Calvin who said, that true wisdom is the knowledge of God and the knowledge of oneself.

The desert fathers were searching for answers to those persistent questions of life – how do I deal with my own sense of importance? My constant need for someone other than myself to give me help in life? When one walks into the desert, the desert cares nothing about you, who you are nor what you bring to it. That desert terrain offers a spiritual antidote for the problem of dealing with that big I in our lives.

Another reason the desert monks went to that desolate place was because in Scripture the desert was a place of evil and temptation. They found precedents in the life of John the Baptist and especially our Lord. Throughout his life, Jesus would withdraw into the desert to pray. Jesus began his ministry in the desert, being tempted 40 days. Similarly, Antony started his ministry by going into the desert to empty himself and ace temptation.

In the desert the monks faced temptations of hunger, power, and beauty – the things missing from everyday life in the solitude of the desert are the things one discovers oneself wanting desperately. The monks looked on demons and temptation as aides to their spiritual lives. But in the midst of the struggles, they discovered God there with them. After they had spent a considerable time in the desert, they could come to love it as abba Marcarius did. But mainly, the monks saw the desert as a place of training for their place in God’s kingdom.

![]()

Their training in the desert forced them to answer two questions: what is it you let go of and what do you hold onto? The spiritual journey of the monks in the desert focused by necessity on those two basics questions of life.

A young man comes to Scetis, west of the Nile, to seek out the great monk Abba Macarius. He asks Abba Macarius, "How do I get to be a holy man? I want to be a holy man. And I want to be one tomorrow."

Macarius smiles and says, "Spend the day tomorrow over at the cemetery. I want you to abuse the dead for all you're worth. Throw sticks and stones at them, curse at them, call them names—anything you can think of. Spend the whole day doing nothing but that."

The young man must have thought the great monk was crazy, but he spent the next day doing everything he was told. When he returned, Abba Macarius asked him, "What did the dead people say out there today?"

The young man responded that they didn't say a thing. They were dead. Macarius said, "Isn't that interesting? I want you to go back tomorrow, and this time spend the day saying everything nice about these people. Call them righteous men and women, compliment them, say everything wonderful you can imagine."

So the young man went back the next day, did as he was told, and returned to Macarius. The monk asked him what the dead people said this time.

"Well, they didn't answer a word again," replied the brother.

"Ah, they must indeed be holy people," said Macarius. "You insulted them, and they did not reply. You praised them, and they did not speak. Go and do likewise, my friend, taking no account of either the scorn of men and women or their praises. And you too will be a holy man."

It's a wonderful story that asks two questions: What do you ignore? The answer is the scorn and praise of others. The other question is more indirect—What do you love? That is, since you are not going to be motivated by what others think, to what are you going to give yourself fully?

The monks learned that the desert teaches you how to live apart from others, how to live without compulsively needing them to give you worth or make you feel loved. In the desert, you learn how to live with yourself. Only then are you capable of giving love—sacrificial love that accepts or needs nothing in return.

It has been suggested that the desert fathers went out to the desert to earn their salvation by means of living lives of deprivation. But we should ask ourselves if that is so.

To try to tease out the answer to that let us think of what the medieval mystic Meister Eckhart once said, that the spiritual life isn't so much a matter of addition as subtraction.

Though we Protestants talk about justification by faith (versus by works), we often act as if the key to the spiritual life is adding all the active virtues, doing great things for God, sharing the gospel with others, and the like. Eckhart said, no, it's a matter of subtraction. How much can you let go of? It's not a matter of anxiously having to prove yourself to your teachers, to your parents, or to God so as to finally make yourself acceptable. It's a matter of letting go of all those compulsive needs for approval and recognizing that only after you abandon those compulsions will you be able to accept God's utterly free grace that comes in the gospel, in Jesus.

The desert is a perfect place to let go of the need for recognition. Gregory of Nyssa back in the fourth century used the image of the canyon cliff. Being on top of that cliff, in a place of beauty and uneasiness—that's where a person discovers the majesty, greatness, and glory of God. One looks at that canyon cliff, think about it being there thousands of years, and I ask myself, how did that canyon cliff change on the day my personal world fell apart?

As Gregory teaches us from way back there in the 300’s, we find, sitting there watching that canyon wall, that it didn't change at all. In the midst of our worlds falling apart, something didn't change. It was waiting, staying there as if for us, in the same way that God does not change. That stone cliff, a metaphor of God, invites us to pour out all the grief and anguish we can muster, then accepts it all without rebuke, receives it all right there in the desert.

Something amazing happens at that point. When we become silent enough and empty enough, pouring out our needs to God in that desert place, we are able for the first time to hear what we had never heard before, and that's a single word whispered by Jesus: love. It's one of those words that we can't hear until we are utterly silent and utterly empty.

Speaking about what the most devout desert monks had experienced, John Climacus wrote, "Lucky the man who longs for God as a smitten lover does for his beloved."

Christian History Home > 1999 > Issue 64 > Antony and the Desert Fathers: Christian History Interview - Discovering the Desert Paradox

Unit 11 Lecture 2

For this lecture, we turn to another article from Christian History magazine in order to learn more about Antony of Egypt, who is called the greatest of the desert fathers.

Antony of Egypt

Greatest Desert Father

![]()

"Wherever you find yourself, do not go forth from that place too quickly. Try to be patient and learn to stay in one place."

Born into a wealthy family, Antony submitted to his parents and their expectations that he follow in their wealthy footsteps. They died when Antony was only about 20 years old, and he inherited every penny. But about that same time, Antony happened to hear a reading from the Gospel of Matthew, where Jesus tells a rich young man, "If you want to be perfect, go and sell everything you have and give the money to the poor." Antony believed he was that rich young man and immediately did exactly as Jesus instructed.

Everything we know about Antony comes from a hagiography (a favorable biography of a saintly person) written shortly after his death by the theologian Athanasius. According to him, Antony saw the Christian's task as both simple and formidable: become a "lover of God" by resisting the Devil and yielding to Christ. Antony saw the world as a battlefield on which God's servants waged war against the Devil and his demons.

His journey into purity began by removing himself from the village. He took up strenuous spiritual exercises: sleepless nights spent in prayer, fasting every other day, and eating only bread and water. He discovered, Athanasius wrote, "the mind of the soul is strong when the pleasures of the body are weak."

Soon Antony left the village territories and sought refuge in nearby tombs where, according to Athanasius, devils and wild beasts assaulted him both physically and spiritually. Like an athlete in the arena, Antony endured repeated attacks until the demons were finally scattered by the presence of God. In the peace after the turmoil, Antony asked God why he had been left to do battle alone. God told him that, though he was present, he waited to see the saint fight.

From the tombs Antony fled again, this time seeking refuge in an abandoned Roman fort on a solitary desert mountain. There he shut himself up for 20 years, waging a silent, solitary battle. When he emerged, Antony had become a symbol of strength and wisdom for all of Egypt.

Having built a foundation of solitude and ceaseless prayer, Antony was ready to share his secrets with others who sought to follow his way. Many were attracted to his wisdom, and these he encouraged to seek self-denial and the life of the hermit. The Apophthegmata, a collection of sayings attributed to the desert fathers and mothers, tells this story of Antony's wisdom:

A brother renounced the world and gave his goods to the poor, but he kept back a little for his personal expenses. He went to see Abba Antony. When he told him this, the old man said to him, "If you want to be a monk, go into the village, buy some meat, cover your naked body with it and come here like that." The brother did so, and the dogs and birds tore at his flesh. When he came back the old man asked him whether he had followed his advice. He showed him his wounded body, and Saint Antony said, "Those who renounce the world but want to keep something for themselves are torn in this way by the demons who make war on them."

Antony also came to the aid of the larger church. When Roman Emperor Diocletian began persecuting Egyptian Christians in 303, word reached the lonesome Antony in his desert cell. He and several other monks traveled to Alexandria and ministered to the persecuted. He was so respected that even the authorities left him alone to evangelize, console, and ease the suffering of the prisoners. In fact, under Maximin he offered himself as a martyr but was refused.

Only one other time did Antony leave his desert solitude. Near the end of Antony's life, Arius (a former deacon in Alexandria) began to spread his heresy that Christ was created, and thus not equal with God. Many Egyptian Christians were swayed by Arian teachings. Athanasius, leader of the church in Alexandria and defender of orthodoxy, called Antony to the Egyptian capital to champion the truth. After preaching, the monk fled the world a last time, returning to his quiet cell. When, at the age of 105, he knew he was near the end of his life, he took two companions with him into the desert to wait for his death. They were ordered to bury his body without a marker so no one could make his grave or relics an object of reverence.

Though Antony was not the first monk, his passion for purity blazed the way for a monastic spirituality. Athanasius's biography became a "best-seller" and inspired thousands to take up the monastic life, which developed into one of the most important institutions in Western history.

Be sure to read excerpts from the sayings of the desert fathers in this week’s readings. You will find that they have much to ponder as we too seek the face of God.

Unit 11 Lecture 3

Athanasius

![]()

"Those who maintain 'There was a time when the Son was not' rob God of his Word, like plunderers."

"Black Dwarf" was the tag his enemies gave him. And the short, dark-skinned Egyptian bishop had plenty of enemies. He was exiled five times by four Roman emperors, spending 17 of the 45 years he served as bishop of Alexandria in exile. Yet in the end, his theological enemies were "exiled" from the church's teaching, and it is Athanasius's writings that shaped the future of the church.

Challenging "orthodoxy"

Most often the problem was his stubborn insistence that Arianism, the reigning "orthodoxy" of the day, was in fact a heresy.

The dispute began when Athanasius was the chief deacon assistant to Bishop Alexander of Alexandria. While Alexander preached "with perhaps too philosophical minuteness" on the Trinity, Arius, a presbyter (priest) from Libya announced, "If the Father begat the Son, then he who was begotten had a beginning in existence, and from this it follows there was a time when the Son was not." The argument caught on, but Alexander and Athanasius fought against Arius, arguing that it denied the Trinity. Christ is not of a like substance to God, they argued, but the same substance.

To Athanasius this was no splitting of theological hairs. Salvation was at issue: only one who was fully human could atone for human sin; only one who was fully divine could have the power to save us. To Athanasius, the logic of New Testament doctrine of salvation assumed the dual nature of Christ. "Those who maintain 'There was a time when the Son was not' rob God of his Word, like plunderers."

Alexander's encyclical letter, signed by Athanasius (and possibly written by him), attacked the consequences of the Arians' heresy: "The Son [then,] is a creature and a work; neither is he like in essence to the Father; neither is he the true and natural Word of the Father; neither is he his true wisdom; but he is one of the things made and created and is called the Word and Wisdom by an abuse of terms… Wherefore he is by nature subject to change and variation, as are all rational creatures."

The controversy spread, and all over the empire, Christians could be heard singing a catchy tune that championed the Arian view: "There was a time when the Son was not." In every city, wrote a historian, "bishop was contending against bishop, and the people were contending against one another, like swarms of gnats fighting in the air."

Word of the dispute made it to the newly converted Emperor Constantine the Great, who was more concerned with seeing church unity than theological truth. "Division in the church," he told the bishops, "is worse than war." To settle the matter, he called a council of bishops.

Of the 1,800 bishops invited to Nicea, about 300 came—and argued, fought, and eventually fleshed out an early version of the Nicene Creed. The council, led by Alexander, condemned Arius as a heretic, exiled him, and made it a capital offense to possess his writings. Constantine was pleased that peace had been restored to the church. Athanasius, whose treatise On the Incarnation laid the foundation for the orthodox party at Nicea, was hailed as "the noble champion of Christ." The diminutive bishop was simply pleased that Arianism had been defeated.

But it hadn't.

Bishop in exile

Within a few months, supporters of Arius talked Constantine into ending Arius's exile. With a few private additions, Arius even signed the Nicene Creed, and the emperor ordered Athanasius, who had recently succeeded Alexander as bishop, to restore the heretic to fellowship.

When Athanasius refused, his enemies spread false charges against him. He was accused of murder, illegal taxation, sorcery, and treason—the last of which led Constantine to exile him to Trier, now a German city near Luxembourg.

Constantine died two years later, and Athanasius returned to Alexandria. But in his absence, Arianism had gained the upper hand. Now church leaders were against him, and they banished him again. Athanasius fled to Pope Julius I in Rome. He returned in 346, but in the mercurial politics of the day, was banished three more times before he came home to stay in 366. By then he was about 70 years old.

While in exile, Athanasius spent most of his time writing, mostly to defend orthodoxy, but he took on pagan and Jewish opposition as well. One of his most lasting contributions is his Life of St. Antony, which helped to shape the Christian ideal of monasticism. The book is filled with fantastic tales of Antony's encounters with the devil, yet Athanasius wrote, "Do not be incredulous about what you hear of him… Consider, rather that from them only a few of his feats have been learned." In fact, the bishop knew the monk personally, and this saint's biography is one of the most historically reliable. It became an early "best-seller" and made a deep impression on many people, even helping lead pagans to conversion: Augustine is the most famous example.

During Athanasius's first year permanently back in Alexandria, he sent his annual letter to the churches in his diocese, called a festal letter. Such letters were used to fix the dates of festivals such as Lent and Easter, and to discuss matters of general interest. In this letter, Athanasius listed what he believed were the books that should constitute the New Testament.

"In these [27 writings] alone the teaching of godliness is proclaimed," he wrote. "No one may add to them, and nothing may be taken away from them."

Though other such lists had been and would still be proposed, it is Athanasius's list that the church eventually adopted, and it is the one we use to this day.

Break and then second section

For this second part of the lecture we go back in time to the history of the church that was written by Socrates Scholasticus about in the year 400. I have a few paragraphs in which he describes what went on at the Council of Nicea at which Athanasius and Arius were the foremost antagonists.

But it may be well to hear what Eusebius says on this subject, in his third book of the Life of Constantine.165 His words are these:

‘A variety of topics having been introduced by each party and much controversy being excited from the very commencement, the emperor listened to all with patient attention, deliberately and impartially considering whatever was advanced. He in part supported the statements which were made on either side, and gradually softened the asperity of those who contentiously opposed each other, conciliating each by his mildness and affability. And as he addressed them in the Greek language, for he was not unacquainted with it, he was at once interesting and persuasive, and wrought conviction on the minds of some, and prevailed on others by entreaty, those who spoke well he applauded. And inciting all to unanimity at length he succeeded in bringing them into similarity of judgment, and conformity of opinion on all the controverted points: so that there was not only unity in the confession of faith, but also a general agreement as to the time for the celebration of the feast of Salvation.166 Moreover the doctrines which had thus the common consent, were confirmed by the signature of each individual.’

Such in his own words is the testimony respecting these things which Eusebius has left us in writing; and we not unfitly have used it, but treating what he has said as an authority, have introduced it here for the fidelity of this history. With this end also in view, that if any one should condemn as erroneous the faith professed at this council of Nicæa, we might be unaffected by it, and put no confidence in Sabinus the Macedonian,167 who calls all those who were convened there ignoramuses and simpletons. For this Sabinus, who was bishop of the Macedonians at Heraclea in Thrace, having made a collection of the decrees published by various Synods of bishops, has treated those who composed the Nicene Council in particular with contempt and derision; not perceiving that he thereby charges Eusebius himself with ignorance, who made a like confession after the closest scrutiny. And in fact some things he has willfully passed over, others he has perverted, and on all he has put a construction favorable to his own views. Yet he commends Eusebius Pamphilus as a trustworthy witness, and praises the emperor as capable in stating Christian doctrines: but he still brands the faith which was declared at Nicæa, as having been set forth by ignorant persons, and such as had no intelligence in the matter. And thus he voluntarily contemns the words of a man whom he himself pronounces a wise and true witness: for Eusebius declares, that of the ministers of God who were present at the Nicene Synod, some were eminent for the word of wisdom, others for the strictness of their life; and that the emperor himself being present, leading all into unanimity, established unity of judgment, and agreement of opinion among them. Of Sabinus, however, we shall make further mention as occasion may require. But the agreement of faith, assented to with loud acclamation at the great council of Nicæa is this:

‘We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible:—and in one168 Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the only-begotten of the Father, that is of the substance of the Father; God of God and Light of light; true God of true God; begotten, not made, consubstantial169 with the Father: by whom all things were made, both which are in heaven and on earth: who for the sake of us men, and on account of our salvation, descended, became incarnate, and was made man; suffered, arose again the third day, and ascended into the heavens, and will come again to judge the living and the dead. [We] also [believe] in the Holy Spirit. But the holy Catholic and Apostolic church anathematizes those who say “There was a time when he was not,” and “He was not before he was begotten” and “He was made from that which did not exist,” and those who assert that he is of other substance or essence than the Father, or that he was created, or is susceptible of change.’170

This creed was recognized and acquiesced in by three hundred and eighteen [bishops]; and being, as Eusebius says, unanimous is expression and sentiment, they subscribed it.