Reading: Monopoly and Antitrust Policy

Monopoly

Monopoly is a market structure consisting

of a firm that is the only seller of a good or service that does not have a

close substitute

Monopoly exists at the opposite end of

the spectrum to perfect competition

We study monopolies for two

reasons:

1.

Some firms truly are monopolists, so it is important to understand how they

behave

2. Firms might collude in order to act like a monopolist; knowing how

monopolies act helps us to identify these firms

Do

Monopolies Really Exist

Suppose you live in a small town with only one pizzeria. Is that pizzeria a monopoly?

1. It has competition from other

fast-food restaurants

2. It has competition from grocery stores that provide pizzas for you to cook

at home

If you consider these alternatives to be close substitutes for pizzeria pizza,

then the pizza restaurant is a monopoly

If

you do not consider these alternatives to be close substitutes for pizzeria

pizza, then the pizza restaurant is a monopoly

Regardless,

the pizzeria’s unique position may afford it some monopoly power to raise

prices, and obtain economic profit.

Where

Do

Monopolies Come From?

For a firm to exist as a monopoly, there must be barriers to entry preventing other firms coming in and competing with it.

The

four main reasons for these barriers are:

1.

Government restrictions on entry

2. Control of a key resource

3. Network externalities

4. Natural monopoly

Government

Restrictions on Entry

In the United States, governments block

entry in two ways:

a. Patents

and copyrights

Newly

developed products like drugs are frequently granted patents, the exclusive

right to produce a product for a period of 20 years from the date the patent

was filed with the government

Similarly,

copyrights provide the exclusive right to produce and sell creative works like

books and films.

Patents and copyrights encourage innovation and creativity, since without them,

firms would be able to substantially profit from endeavors.

In the U.S., governments block entry in

two main ways:

b. Public

franchises

A government designation that a firm is the only legal provider of a good or service is known as a public franchise. These might exist, for example, in electricity or water markets.

Sometimes (more commonly in Europe than

the U.S.) governments operate these firms as a public enterprise.

- An example of this is the U.S. Postal Service.

Control

of a Key Resource

For many years, the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) either owned or had long-term contracts for almost all of the world’s supply of bauxite, the mineral from which we obtain aluminum.

-

Such control over a key resource served as substantial barrier to entry for

additional firms.

The

National Football League (NFL) acts as a monopoly in this manner too: it

ensures that the majority of the world’s best football players are under

contract to the NFL, and unable to be used for another potential league.

Network

Externalities

Economists refer to network externalities as a product characteristics whereby the usefulness of a product increases with the number of consumers who use it.

Examples: Auction sites (like Ebay)

Computer operating systems (like Windows

Social networking sites (like Facebook)

These network externalities can set off a virtuous cycle for a firm, allowing the value of its products to continue to increase, along with the price it can charge.

But consumers may be locked into an inferior product.

Average Total Cost Curve for a Natural Monopoly

A natural monopoly occurs when economies

of scale are so large that one firm can supply the entire market at a lower

average total cost can two or more firms.

In the market for electricity delivery, a single firm (point A) can deliver

electricity at a lower cost than can two firms (point B).

Natural monopolies are most likely when fixed costs are high.

Calculating

a Monopoly’s Revenue

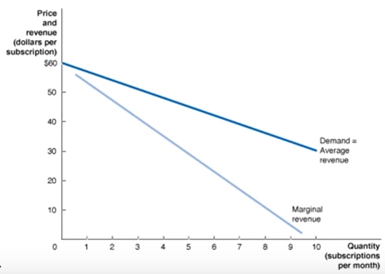

Time Warner Cable is a monopolist in a

local market for cable television services.

The first two columns of the table show the market demand curve, which is also

Comcast’s demand curve.

Total, average, and marginal revenue are calculated in the usual manner.

A monopolist decreases price to expand

output, two effects occur:

1. Revenue increases from selling an extra unit of output.

2. Revenue decreases, because price reduction is shared with existing

customers.

So marginal revenue is always below demand for a monopolist.

Long

Run Profits for a Monopoly

Since there are barriers to entry,

additional firms cannot enter the market.

- So

there is no distinction between short run and long run for a monopoly

Then unlike for monopolistic competition, we expect monopolists to continue to

earn profits in the long run.

An

Argument in Favor of Market Power

Market power may produce some benefit for an economy: the prospect of market power (and the resulting economic profits) drives firms to innovate, creating new products and services.

The Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter

claimed that this drive would create a “gale of creative destruction” that

would eventually benefit consumers more than increased price competition.

- This helps to explain governmental ambivalence regarding large firms with market power

Government

Policy Toward Monopoly

Because monopolies reduce consumer

surplus and economic efficiency, governments regulate their behavior.

- Many governments try to stop firms from colluding, and seek to prevent

mergers and acquisitions creating larger firms, through antitrust laws.

Collusion: An agreement among firms to charge the same price or otherwise not to compete.

Antitrust

laws: Laws aimed at eliminating collusion and promoting competition among

firms