Reading: History of Peru

Pre-Columbian cultures

Hunting tools dating back to more than 11,000 years ago have been found inside the caves of Pachacamac, Telarmachay, Junin and Lauricocha.[1] Some of the oldest civilizations appeared circa 6000 BC in the coastal provinces of Chilca and Paracas, and in the highland province of Callejón de Huaylas. Over the following three thousand years, inhabitants switched from nomadic lifestyles to cultivating land, as evidence from sites such as Jiskairumoko, Kotosh and Huaca Prieta demonstrates. Cultivation of plants such as corn and cotton (Gossypium barbadense) began, as well as the domestication of animals such as the wild ancestors of the llama, the alpaca and the guinea pig. Inhabitants practiced spinning and knitting of cotton and wool, basketry and pottery.

As these inhabitants became sedentary, farming allowed them to build settlements and new societies emerged along the coast and in the Andean mountains. The first known city in the Americas was Caral, located in the Supe Valley 200 km north of Lima. It was built in approximately 2500 BC.[2]

What is left from the civilization, also called Norte Chico, is about 30 pyramidal structures built up in receding terraces ending in a flat roof; some of them measured up to 20 meters in height. Caral is one of the world centers of the rise of civilization.[2]

In the early 21st century, archeologists have discovered new evidence of ancient pre-Ceramic complex cultures. In 2005 Tom D. Dillehay and his team announced the discovery of three irrigation canals that were 5,400 years old, and a possible fourth that is 6,700 years old, all in the Zaña Valley in northern Peru, evidence of community activity to support improved agriculture at a much earlier date than previously believed.[3] In 2006, Robert Benfer and a research team discovered a 4,200-year-old observatory at Buena Vista, a site in the Andes several kilometers north of present-day Lima. They believe the observatory was related to the society's reliance on agriculture and understanding the seasons. The site includes the oldest three-dimensional sculptures found thus far in South America.[4] In 2007 the archeologist Walter Alva and his team found a 4,000-year-old temple with painted murals at Ventarrón, in the northwest Lambayeque region. The temple contained ceremonial offerings gained from exchange with Peruvian jungle societies, as well as those from the Ecuadoran coast.[5] Such finds show sophisticated, monumental construction requiring large-scale organization of labor, suggesting that hierarchical, complex cultures arose in South America much earlier than scholars had thought.

Many other civilizations developed and were absorbed by the most powerful ones such as Kotosh, Chavin, Paracas, Lima, Nasca, Moche, Tiwanaku, Wari, Lambayeque, Chimu and Chincha, among others. The Paracas culture emerged on the southern coast around 300 BC. They are known for their use of vicuña fibers instead of just cotton to produce fine textiles—innovations that did not reach the northern coast of Peru until centuries later. Coastal cultures such as the Moche and Nazca flourished from about 100 BC to about AD 700: the Moche produced impressive metalwork, as well as some of the finest pottery seen in the ancient world, while the Nazca are known for their textiles and the enigmatic Nazca lines.

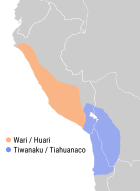

These coastal cultures eventually began to decline as a result of recurring el Niño floods and droughts. In consequence, the Huari and Tiwanaku, who dwelt inland in the Andes became the predominant cultures of the region encompassing much of modern-day Peru and Bolivia. They were succeeded by powerful city-states, such as Chancay, Sipan, and Cajamarca, and two empires: Chimor and Chachapoyas culture These cultures developed relatively advanced techniques of cultivation, gold and silver craft, pottery, metallurgy, and knitting. Around 700 BC, they appear to have developed systems of social organization that were the precursors of the Inca civilization.

In the highlands, both the Tiahuanaco culture, near Lake Titicaca in both Peru and Bolivia, and the Wari culture, near the present-day city of Ayacucho, developed large urban settlements and wide-ranging state systems between 500 and 1000 AD.[6]

Not all Andean cultures were willing to offer their loyalty to the Incas as the Incas expanded their empire, and many were openly hostile. The people of the Chachapoyas culture were an example of this, but the Inca eventually conquered and integrated them into their empire.

Inca Empire (1438–1532)[edit]

The Incas built the largest empire and dynasty of pre-Columbian America.[7] The Tahuantinsuyo—which is derived from Quechua for "The Four United Regions"—reached its greatest extension at the beginning of the 16th century. It dominated a territory that included (from north to south): Ecuador, part of Colombia, the northern half of Chile, and the northwest part of Argentina; and from east to west, from Bolivia to the Amazonian forests and Peru.

The empire originated from a tribe based in Cusco, which became the capital. Pachacutec wasn't the first Inca, but he was the first ruler to considerably expand the boundaries of the Cusco state- probably he could be compared to Alexander the great (from Greece), Julius Caesar (of the Roman empire), Attila (from the Hunns tribes) and Genghis Khan (from the Mongols empire). His offspring later ruled an empire by both violent invasions and peaceful conquests- i.e. intermarriages among the rules of small kingdoms and the current Inca ruler.

In Cuzco, the royal city was created to resemble a cougar; the head, the main royal structure, formed what is now known as Sacsayhuamán. The Empire's administrative, political, and military center was located in Cusco. The empire was divided into four quarters: Chinchaysuyu, Antisuyu, Kuntisuyu and Qullasuyu.

The official language was Quechua – imposed on the citizens. It was the language of a neighbouring tribe of the original tribe of the empire. Conquered populations—tribes, kingdoms, states, and cities—were allowed to practice their own religions and lifestyles, but had to recognize Inca cultural practices as superior to their own. Inti, the sun god, was to be worshipped as one of the most important gods of the empire. His representation on earth was the Inca ("Emperor").

The Tawantinsuyu was organized in dominions with a stratified society, in which the ruler was the Inca. It was also supported by an economy based on the collective property of the land.

Many unusual customs were observed, for example the extravagant feast of Inti Raymi which gave thanks to the God Sun, and the young women who were the Virgins of the Sun, sacrificial virgins devoted to the Inti. The empire, being quite large, also had an impressive transportation system of roads to all points of the empire called the Inca Trail, and chasquis, message carriers who relayed information from anywhere in the empire to Cusco.

Machu Picchu (Quechua for "old peak"; sometimes called the "Lost City of the Incas") is a well-preserved pre-Columbian Inca ruin located on a high mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley, about 70 km (44 mi) northwest of Cusco. Elevation measurements vary depending on whether the data refers to the ruin or the extremity of the mountain; Machu Picchu tourist information reports the elevation as 2,350 m (7,711 ft)[1]. Forgotten for centuries by the outside world, although not by locals, it was brought back to international attention by Yale archaeologist Hiram Bingham III, who rediscovered it in 1911 and wrote a best-selling work about it. Peru is pursuing legal efforts to retrieve thousands of artifacts that Bingham removed from the site that are in possession at Yale. Bingham sold them to Yale.[8]

Although Machu Picchu is by far the most well-known internationally, Peru boasts many other sites where the modern visitor can see extensive and well-preserved ruins, remnants of the Inca-period and even older constructions. Much of the Inca architecture and stonework found at these sites continues to confound archaeologists. For example, at Sacsaywaman in Cusco the zig-zag-shaped walls are composed of massive boulders fitted very precisely to one another's irregular, angular shapes. No mortar holds them together, but nonetheless they have remained absolutely solid through the centuries, surviving earthquakes that flattened many of the colonial constructions of Cusco. Damage to the walls visible today was mainly inflicted during battles between the Spanish and the Inca, as well as later, in the colonial era. As Cusco grew, the walls of Sacsaywaman were partially dismantled, the site becoming a convenient source of construction materials for the city's newer inhabitants. It is still not known how these stones were shaped and smoothed, lifted on top of one another (they really are very massive), or fitted together by the Incas; we also do not know how they transported the stones to the site in the first place. The stone used is not native to the area and most likely came from mountains many kilometers away.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Peru