Reading: Ottoman Empire and the Classical Age

Rise of the Ottoman Empire (1299–1453)

With the demise of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum (c. 1300), Anatolia was divided into a patchwork of independent states, the so-called Anatolian Beyliks. By 1300, a weakened Byzantine Empire had lost most of its Anatolian provinces to these Turkish principalities. One of the beyliks was led by Osman I (d. 1323/4), from which the name Ottoman is derived, son of Ertuğrul, around Eskişehir in western Anatolia. In the foundation myth expressed in the story known as "Osman's Dream", the young Osman was inspired to conquest by a prescient vision of empire (according to his dream, the empire is a big tree whose roots spread through three continents and whose branches cover the sky).[1] According to his dream the tree, which was Osman's Empire, issued four rivers from its roots, the Tigris, the Euphrates, the Nile and the Danube.[1] Additionally, the tree shaded four mountain ranges, the Caucasus, the Taurus, the Atlas and the Balkan ranges.[1] During his reign as Sultan, Osman I extended the frontiers of Turkish settlement toward the edge of the Byzantine Empire.

During this period, a formal Ottoman government was created whose institutions would change drastically over the life of the empire.

In the century after the death of Osman I, Ottoman rule began to extend over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. Osman's son, Orhan, captured the city of Bursa in 1326 and made it the new capital of the Ottoman state. The fall of Bursa meant the loss of Byzantine control over Northwestern Anatolia. The important city of Thessaloniki was captured from the Venetians in 1387. The Ottoman victory at Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe. The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, widely regarded as the last large-scale crusade of the Middle Ages, failed to stop the advance of the victorious Ottoman Turks. With the extension of Turkish dominion into the Balkans, the strategic conquest of Constantinople became a crucial objective. The Empire controlled nearly all former Byzantine lands surrounding the city, but the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when Timur invaded Anatolia in the Battle of Ankara in 1402. He took Sultan Bayezid I as a prisoner. The capture of Bayezid I threw the Turks into disorder. The state fell into a civil war that lasted from 1402 to 1413, as Bayezid's sons fought over succession. It ended when Mehmed I emerged as the sultan and restored Ottoman power, bringing an end to the Interregnum.

Sultan Mehmed I. Ottoman miniature, 1413-1421

Part of the Ottoman territories in the Balkans (such as Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Kosovo) were temporarily lost after 1402, but were later recovered by Murad II between the 1430s and 1450s. On 10 November 1444, Murad II defeated the Hungarian, Polish and Wallachian armies under Władysław III of Poland (also King of Hungary) and János Hunyadi at the Battle of Varna, which was the final battle of the Crusade of Varna.[2][3] Four years later, János Hunyadi prepared another army (of Hungarian and Wallachian forces) to attack the Turks, but was again defeated by Murad II at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448.

The son of Murad II, Mehmed the Conqueror, reorganized the state and the military, and demonstrated his martial prowess by capturing Constantinople on 29 May 1453, at the age of 21.

Classical Age (1453–1550)

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II cemented the status of the Empire as the preeminent power in southeastern Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. After taking Constantinople, Mehmed met with the Orthodox patriarch, Gennadios and worked out an arrangement in which the Orthodox Church, in exchange for being able to maintain its autonomy and land, accepted Ottoman authority.[4] Because of bad relations between the latter Byzantine Empire and the states of western Europe as epitomized by Loukas Notaras's famous remark "Better the Sultan's turban than the Cardinal's Hat", the majority of the Orthodox population accepted Ottoman rule as preferable to Venetian rule.[4]

Upon making Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) the new capital of the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Mehmed II assumed the title of Kayser-i Rûm (literally Caesar Romanus, i.e. Roman Emperor.) In order to consolidate this claim, he would launch a campaign to conquer Rome, the western capital of the former Roman Empire. To this aim he spent many years securing positions on the Adriatic Sea, such as in Albania Veneta, and then continued with the Ottoman invasion of Otranto and Apulia on 28 July 1480. The Turks stayed in Otranto and its surrounding areas for nearly a year, but after Mehmed II's death on 3 May 1481, plans for penetrating deeper into the Italian peninsula with fresh new reinforcements were given up on and cancelled and the remaining Ottoman troops sailed back to the east of the Adriatic Sea.

During this period in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a long period of conquest and expansion, extending its borders deep into Europe and North Africa. Conquests on land were driven by the discipline and innovation of the Ottoman military; and on the sea, the Ottoman Navy aided this expansion significantly. The navy also contested and protected key seagoing trade routes, in competition with the Italian city states in the Black, Aegean and Mediterranean seas and the Portuguese in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean.

The state also flourished economically due to its control of the major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia.[5]

The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective Sultans. Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) dramatically expanded the Empire's eastern and southern frontiers by defeating Shah Ismail of Safavid Persia, in the Battle of Chaldiran.[6] Selim I established Ottoman rule in Egypt, and created a naval presence on the Red Sea. After this Ottoman expansion, a competition started between the Portuguese Empire and the Ottoman Empire to become the dominant power in the region.[7]

Selim's successor, Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), further expanded upon Selim's conquests. After capturing Belgrade in 1521, Suleiman conquered the southern and central parts of the Kingdom of Hungary. (The western, northern and northeastern parts remained independent.)[8][9]

After his victory in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, he established Turkish rule in the territory of present-day Hungary (except the western part) and other Central European territories, (See also: Ottoman–Hungarian Wars). He then laid siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city after the onset of winter forced his retreat.[10]

In 1532, he made another attack on Vienna, but was repulsed in the Siege of Güns, 97 kilometres (60 mi) south of the city at the fortress of Güns.[11][12] In the other version of the story, the city's commander, Nikola Jurišić, was offered terms for a nominal surrender.[13] However, Suleiman withdrew at the arrival of the August rains and did not continue towards Vienna as previously planned, but turned homeward instead.[13][14]

After further advances by the Turks in 1543, the Habsburg ruler Ferdinand officially recognized Ottoman ascendancy in Hungary in 1547. During the reign of Suleiman, Transylvania, Wallachia and, intermittently, Moldavia, became tributary principalities of the Ottoman Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took Baghdad from the Persians in 1535, gaining control of Mesopotamia and naval access to the Persian Gulf. By the end of Suleiman's reign, the Empire's population totaled about 15,000,000 people.[15]

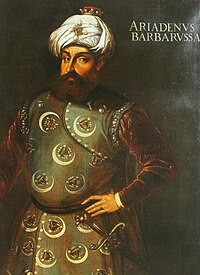

Under Selim and Suleiman, the Empire became a dominant naval force, controlling much of the Mediterranean.[16] The exploits of the Ottoman admiral Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha, who commanded the Ottoman Navy during Suleiman's reign, led to a number of military victories over Christian navies. Important naval victories of the Ottoman Empire in this period include the Battle of Preveza (1538); Battle of Ponza (1552); Battle of Djerba (1560); conquest of Algiers (in 1516 and 1529) and Tunis (in 1534 and 1574) from Spain; conquest of Rhodes (1522) and Tripoli (1551)from the Knights of St. John; capture of Nice (1543) from the Holy Roman Empire; capture of Corsica (1553) from the Republic of Genoa; capture of the Balearic Islands (1558) from Spain; capture of Aden (1548), Muscat (1552) and Aceh (1565–67) from Portugal during the Indian Ocean expeditions; among others.

Suleiman's policy of expansion throughout the Mediterranean basin was however halted in Malta in 1565. During a summer-long siege which was later to be known as the Siege of Malta, the Ottoman forces which numbered around 50,000 fought the Knights of St. John and the Maltese garrison of 6000 men. Stubborn resistance by the Maltese led to the lifting of the siege in September. The unsuccessful siege (the Turks managed to capture the Isle of Gozo together with Fort Saint Elmo on the main island of Malta, but failed elsewhere and retreated) was the second and last defeat experienced by Suleiman the Magnificent (who died a year later, in 1566) after the likewise inconclusive first Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529. The Battle of Lepanto in 1571 (which was triggered by the Ottoman capture of Venetian-controlled Cyprus in 1570) was another major setback for Ottoman naval supremacy in the Mediterranean Sea, despite the fact that an equally large Ottoman fleet was built in a short time and Tunisia was recovered from Spain in 1574.

The conquests of Nice (1543) and Corsica (1553) occurred on behalf of France as a joint venture between the forces of the French king Francis I and the Ottoman sultan Suleiman I, and were commanded by the Ottoman admirals Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha and Turgut Reis.[17] A month prior to the siege of Nice, France supported the Ottomans with an artillery unit during the Ottoman conquest of Esztergom in 1543. France and the Ottoman Empire, united by mutual opposition to Habsburg rule in both Southern and Central Europe, became strong allies during this period. The alliance was economic and military, as the sultans granted France the right of trade within the Empire without levy of taxation. By this time, the Ottoman Empire was a significant and accepted part of the European political sphere. It made a military alliance with France, the Kingdom of England and the Dutch Republic against Habsburg Spain, Italy and Habsburg Austria.

As the 16th century progressed, Ottoman naval superiority was challenged by the growing sea powers of western Europe, particularly Portugal, in the Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean and the Spice Islands. With the Ottoman Turks blockading sea-lanes to the East and South, the European powers were driven to find another way to the ancient silk and spice routes, now under Ottoman control. On land, the Empire was preoccupied by military campaigns in Austria and Persia, two widely separated theatres of war. The strain of these conflicts on the Empire's resources, and the logistics of maintaining lines of supply and communication across such vast distances, ultimately rendered its sea efforts unsustainable and unsuccessful. The overriding military need for defence on the western and eastern frontiers of the Empire eventually made effective long-term engagement on a global scale impossible.