Reading: Evangelism book chapter 4-5

Chapter 4: WHAT IS EVANGELISM?

JACK BLEW HIS NOSE LOUDLY INTO YET ANOTHER TIS- sue. He wasn’t sure which he minded more: the stuffy pres- sure inside his head, or the rough tissues against his nose.

Hudson’s voice boomed in his ear from 3,000 miles away. “So what kind of evangelism do they use?” he asked.

“Evangelism?” Jack spoke feebly.

“If the movement has grown as large and as quickly as you say, then they must have discovered some effective form of evangelism.”

Jack sneezed again. “I don’t think I’ve seen any,” he said. “No one’s accosted me with so much as a pamphlet.” Hudson chuckled. “Well, evangelism isn’t always as

brazen as that.”

“Really?” Jack asked, intrigued. “I always thought the word implied a certain aggressiveness. At my old job there was this lady who was always pushing vitamins on every- body — we would call her the vitamin evangelist.”

Hudson was no longer laughing. “I know what you mean. The sad truth is that even within the church, where we should know better, evangelism has this negative con- notation of being a sales pitch. That’s probably why so few people are interested in it, and even fewer follow through.” “So it isn’t about twisting somebody’s arm?”

“Of course not,” Hudson said. “The word evangelism comes from a Greek word that means ‘telling the good news.’ It may take many forms, but evangelism is simply letting others know the good news of God’s forgiveness. It’s helping people take their first step toward God.”

“Interesting,” Jack said, considering the idea. “Then I

suppose I have seen a form of evangelism.”

“Great,” Hudson said, his mood brightening. “Describe it to me.”

Jack took a moment to find the words. “It seems that new people get interested because members of the move- ment are getting involved in their lives. These people have a big emphasis on getting together — to pray, to sing, to read the Bible, to learn, to eat together, to talk about their lives. The best I can figure it, the new people learn, by watching the old people, how to get close to God.”

“Hmm — sounds like you’re describing discipleship,” Hudson said. “That’s a whole different ball game.”

“Discipleship?” Jack asked hesitantly.

Hudson chuckled again. “Sorry to keep dumping my Christian jargon on you,” he said. “Discipleship is the next step after evangelism. First a person needs to come to Christ: We give a presentation or show a film, and we ask people to commit their lives to God. If they accept, then we begin discipleship — we show them what it means to live as a Christian. We teach them to read the Bible, get them into groups, get them involved in church, get them into classes.” Jack struggled to make sense of this. “I don’t know, Mr. Hudson. I’ve noticed a lot of the second part happen- ing, but none of the first.”

“What are you saying? That ... they’re skipping evan- gelism? They’re just discipling non-believers?”

Jack shrugged. “I can’t really say. I’m not sure I under- stand the distinction between the two stages.”

He heard Hudson open a drawer in his desk. “Well, the Bible is quite clear about the importance of evangelism — it’s the very last thing Jesus said to his followers,” Hudson said. Jack could hear pages of a book turning. “We call it

‘The Great Commission’ — here it is: ‘Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach- ing them to obey everything I have commanded you.’”

“I’m not an expert on this,” Jack said slowly, not want- ing to offend, “but Jesus didn’t say ‘go and evangelize.’ He said ‘go and make disciples.’” He felt a slight rush of warmth as he found himself engaged with this puzzle.

Hudson remained silent for several seconds. “I never noticed that,” he said at last. “Of course, evangelism is implied. You can’t very well disciple someone before you’ve won them over.”

“You can’t?” Jack said. “But that’s exactly what I’m seeing here.”

Hudson seemed to mull this over. “I’ve been getting ahead of myself,” he said amiably. “Why don’t you finish telling me what you’ve seen, and then maybe I’ll have a better idea of their evangelism style.”

Jack tried to think of a way to put his observations into words. His mind grabbed at a conversation he’d had yesterday with a young woman. She’d used a metaphor he hadn’t understood at the time — but now it seemed quite relevant. “Is it common Christian jargon to refer to yourself as ‘dating God’?” he asked.

“Not really,” Hudson said. “The church is referred to as the bride of Christ, but that’s as close as I’ve heard.”

“The other day I met this woman who said she was not a Christian but she still attended the gatherings of the movement in her neighborhood. When I asked her why she bothered, she said she and God were still in the dating stage.” Jack laughed. “It sounded a little weird to me; maybe because I’m a guy. But she went on to explain that she’s still in the process of getting to know God. They’ve been intro- duced, she’s spent a little time with Him, but she wants to know that she loves Him before she makes a commitment.”

“Interesting.”

“To be honest, I hadn’t understood her metaphor until you mentioned ‘winning people over.’ That’s the kind of evangelism I’ve experienced most of my life: People want to sign me up within the first few minutes that we meet.” Jack hoped that hadn’t sounded too insulting. “But here in England, it’s more like — they just want to start me out on a blind date with God. They invite me to hang out with other people who are dating God or have gone on to marry Him. They talk about the ups and downs and the joys and frustrations of being with Him. But in the end, they seem to trust God to win me over in His own time.”

“And this works?” Hudson said, sounding both skepti- cal and impressed. “But — without a commitment up front, how do they keep people coming back week after week?”

“I don’t know — why to do two people decide to keep dating?” Jack asked. “I suppose it’s because they’re on a

journey together. They’re enjoying the

process.”

“Still ... it just seems like it would take forever to move a new person through that process. It’s natural for disciple- ship to take a while, but evangelism has to be more direct.” Jack felt his spirits dampen. He was a writer, after all,

but he couldn’t seem to find the words to make clear what he had seen here. “Look, maybe you Christians get lost in your jargon sometimes,” he said bluntly. “You try to draw a line between evangelism and discipleship, but they’re not that different. They’re both about helping another person get close to God.”

Hudson cleared his throat, interrupting. “There is a line, though. One is for people who haven’t committed to God, and the other for those who have.”

“There you go, then — the main difference isn’t what you do, only what person you do it to,” Jack offered. “If the best way to grow close to God is by classes, groups, and prayer, shouldn’t everyone use those techniques? Evangelism shouldn’t look all that different from discipleship.”

Hudson took a minute to continue the conversation. “I admit I don’t understand this form of evangelism you’re seeing,” he said at last, “but I’m quite interested. Why don’t you keep digging, tell me what you turn up, and maybe we’ll discover a key to explaining it more fully.”

Jack let out a raspy cough. As soon as he was back on his feet, it was time to step up his investigation a notch. It was time to find out what made these people tick.

CHAPTER 5: CREATING A CULTURE OF EVANGELISM

THE STORY WAS NOT COMING TOGETHER. DESPITE HIS help from Hudson, Jack feared his lack of a Christian background put blinders on him. Every answer seemed to lead to three new questions.

He sighed heavily. If there was a common thread running through his research — a thin one, admittedly — it was the couple he was about to meet. More of his leads pointed to these people’s door than any other — although, if he were honest, there were many leads that went elsewhere.

It was funny; for the fastest-growing church in England, it managed to stay fairly inconspicuous. The mainline churches were only vaguely aware of it. It was- n’t home to a flurry of civic activities and meetings. Its handouts didn’t even feature a slick logo. It was the peo- ple on the street who talked about it, who passed on sto- ries of what happened there, who spoke of the leadership of Rev. Edwards and his family.

“Come by for supper,” Edwards had said. He hadn’t wanted to meet at the church building — “Not much to see there, anyway.”

So here Jack was, standing on the porch of a little townhouse just outside London, holding a bottle of sparkling juice. He was smart enough to know some Christian groups drank wine and some did not — why not play it safe?

The door opened and a young woman, balancing a child on her hip, greeted him. Behind her, a dog yipped a greeting as well.

“You must be Jack,” she said. “Come on in. Don’t mind the dog. Or the boy — neither one bites.”

Jack smiled and followed her into the house. As he walked, he instinctively took in his surroundings. In the hallway he saw the usual collection of photos of grand- parents, parents, and growing children — but they were arranged along the branches of a brown tree trunk paint- ed on the wall. The frames and mats, he noted, were all green. In the main room he saw a well-worn drum in one corner, and in the other corner a miniature building proj- ect — an ancient temple or something. A set of crayon drawings hung around the room depicted bearded men in bathrobes. Scenes from Bible stories, he deduced. These people had things going on in their family.

“I’m Sue, by the way, and this young one is Kenneth,” the woman said. The boy, who looked about three years old, buried his face in his mother’s side at being introduced.

“Byron’s going to be a few minutes late,” she told him. “Understand that he doesn’t normally do this — we like to be here for our guests. Hospitality is one of our themes around here.” She pointed to a plaque that read: Our family mission is to walk with God and share that walk with others through words, actions, and hospitality.

“That’s a great idea,” Jack said. “It would give you something to strive for, I imagine. In my family, our only mission was to survive each other.” He grinned.

Behind him, a girl’s voice asked if he wanted any water or juice. Jack turned to answer, and saw that she was nearly the same age as his own daughter, nine or so. He was reminded of the prospect of missing spring break with Bethy, and his heart sank.

“Tell you what,” he said warmly, recovering his smile. “I’ll trade you this juice for some water.” He held the bottle out to her.

“That’s Charlotte,” Sue said as her daughter took the juice to the kitchen. “Quite the little helper.”

The two adults sat down and began talking about raising children, and Charlotte brought back two glasses of water for them. Kenneth began racing in circles to make himself dizzy.

“So ... you’re a reporter, right?” she asked abruptly, her eyes betraying a sense of worry.

“That’s right.”

“Well, maybe I shouldn’t say this,” Sue said, “but we’re a little nervous about your being here — about the publicity.”

Jack frowned. “Why? Are you afraid I’ll make you look bad?”

“No, we’re afraid you’ll make us look good.”

“And why would you be against that?” Jack asked. Sue concentrated on her drink, wiping condensation

from the glass. Then she met Jack’s eyes. “Because every- thing that has happened, all the good things, the thou- sands of lives that have been changed for the good — it has all happened without it.”

Jack nodded slowly. “So why change the game plan now, right?”

“Yes, but it’s more than that,” Sue said. “I guess I, personally, would fear that if you write some favorable article, church leaders and pastors would start coming by to find our secret. They’d invite us to speak at their next conference on church growth. They’d reduce what is hap- pening to some marketable format or formula.”

Jack understood. “Like using the family mission, you mean.”

“Exactly.” Sue brightened. “It’s not just one piece or another that makes a difference — it’s a whole host of things that together make up our church culture.”

“A culture?” Jack asked, but his question was drowned out by the dog starting to yip again. Jack and Sue turned to see Byron enter the room.

“Sorry I’m so late,” Byron said. “We like to be here for our guests.” He, too, pointed to the mission statement on the wall. Jack took note that he and his wife were con- sistent. “It’s nice to meet you at last.”

The two men shook hands, and Sue ushered the group into the dining room for dinner. Jack watched as Byron, Sue, and Charlotte brought out food from the kitchen and arranged it on the table.

“So tell me, Jack,” Byron said,

as he placed a salad on the table, “what do you do when you’re not being a reporter?”

Jack had to think about that for a moment. “To be honest, I’m usually wrapped up with my job or taking the kids out somewhere. But I suppose you’d find me out- doors when I take time off. Fishing, maybe a bit of hiking. I like to take walks, get the blood pumping.”

Byron sat down next to Jack. “Fishing, eh? I do a spot of fishing myself. Nothing like teaching your kids how to fish, is there?”

“Actually, I haven’t taken them fishing yet,” Jack said. “Bethy, that’s my oldest, won’t touch a worm, and Scott’s still too young.”

“No such thing as too young,” Byron said insistently. “Kenneth here can’t hold a rod or thread a hook, but he knows how much Daddy loves to fish. And when you get right down to it, that’s the key to teaching someone how to fish. You share it with someone because you love it, and that’s contagious.”

Jack nodded, surprised at how much sense Byron made. He’d always thought he loved fishing just because he’d been doing it for so long, but it had been his grand- father who’d taught him. There’d been something so joy- ful about those summer weekends.

“Honey,” Sue interrupted. “I think we’re all set now.” “You know what that means, kids,” Byron said.

“Does everyone know the verse of the month?”

“Of course, Daddy,” Charlotte answered, beaming. Together, the four of them recited: “Mark 1:17 — ‘Come, follow me,’ Jesus said, ‘and I will make you fishers of men.’”

Byron praised the kids for their efforts — Kenneth had remembered perhaps half the words — and then said grace for the meal.

Jack spent the prayer thinking about the Bible verse he’d heard. He could relate; he’d often felt like a fish that Christians were trying to hook. They’d dangle just about any kind of bait out there in order to stick him. Jack won- dered what perspective Byron, as a fisherman, would have on it.

“Explain this idea of ‘fishing for men’ to me,” Jack said casually, as he served himself a slice of beef Wellington. “Because a lot of times I feel like Christians are out to bait and hook me — it’s like entrapment for sport.”

Byron let Jack’s question hang in the air momentari- ly. “It’s a metaphor,” he said at last, “and, like any metaphor, it can be stretched too far. The truth is, we’ve often treated non-Christians like fish, and we’ve used a verse like this to justify it.

“But let’s place the statement in its original context. Fishing was not a sport 2,000 years ago; it was a trade. It was a livelihood. It was something that your father and grandfather had done before you, that you had been apprenticed in growing up. It was an identity. It was a pas- sion. When Jesus comes along and says he wants to make Peter and Andrew into fishers of men, he was giving them a new identity, a new passion. He was giving them some- thing new to pass down, to apprentice others in.”

Jack passed the serving plate of roasted potatoes on to

Sue. “So what’s this new job look like?” he asked.

“What does it mean to fish men?”

Byron took a sip of his sparkling juice. “The first three words of the verse tell us — Jesus says, ‘Come, fol- low me.’ He invites them to walk alongside Him, to be part of His life. He fishes them right out of their old life and into a new one. If there’s any model for fishing men, it’s right there: inviting others to walk alongside Jesus with you.”

Jack chewed a bite of potatoes and tried to digest what Byron had said. He’d underestimated how interest- ing the Bible could be.

“So it’s not about baiting anybody?” he said.

“Not at all,” Byron answered. “A fisher of fish usual- ly cares about catching something, but a fisher of men? He wants to pass something on.”

Loud truck noises erupted from Kenneth’s place at the table as he began driving a chicken strip around the edge of his plate. The conversation turned toward what was and was not appropriate for the dinner table, with Charlotte voicing the strictest position.

“So tell me, Jack, what would you like to know about our church?” Byron said. “What questions do you have for

us?”

Jack brought his attention back to business. He put down his knife and fork and gathered his thoughts. “I know that you guys are reluctant to dissect this move- ment, and that no one part of it makes it work” — he nod- ded toward Sue — “so I’m not exactly sure where to begin my questions.”

Byron smiled. “Personally, I’m curious to know what it looks like from your vantage point. What do you make of all this?”

“All right,” Jack said. “It seems clear that wherever Christianity has been in the past, it is now struggling ... yet somehow your version of evangelism flourishes. I just can’t put my finger on why. The most unusual thing I’ve noticed is that every single Christian I’ve talked to here — or at least 99 percent of them — has wanted to share something about their life with me. So is that the key: get- ting full participation from your church?”

“Interesting,” Byron said, and paused to mull it over. “I can see how you would think that. Most churches have about five percent of people involved in evangelism, and we have nearly full participation, so it would follow that we would grow much faster. But no, I’m quite sure that full participation is a side effect of the movement, not its cause.”

“How can you know?”

Byron talked as he cut his meat. “Think of it this way: If you lost a lot of weight eating a new miracle snack bar, you’d be pretty excited, right? You’d probably tell people about this snack whenever someone mentioned losing weight. You wouldn’t be able to help yourself. But if someone came along and told you that you had to sell a case of snack bars to every person you met, you’d sud- denly get really quiet about it. Almost all people are will- ing to talk about themselves — it’s one of our most favorite subjects. But only about five percent of people are cut out to sell something.”

“So you’re saying the approach you use determines the participation you get,” Jack said.

“Right — and I learned that the hard way,” Byron said. “I have a seller personality, so for years I participat- ed in all kinds of selling techniques: tracts, crusades, door- to-door evangelism, street ministries, dramas in the park, seeker-sensitive services, videos, literature, classes.”

“I’m not exactly sure what all those are,” Jack said tentatively.

“Well, don’t worry about them,” Byron said, waving the thought away with his hand. “The point is that I kept trying to get churchgoers to join me in these programs, and I found I could only attract certain personalities. The first kind were people like me, the born salesmen. We thrive on getting rejected over and over so that, when someone accepts, we experience a little high. Later on I realized that perhaps I was in evangelism for that little high I got.

“I could also attract the duty-bound personality. These types see the command in the Bible to go and share with others, and feel good about themselves only when they obey.”

“That’s my personality type,” Sue offered. “I was doing evangelism because it relieved my guilt over a task undone.”

“Right,” Byron said, “most of us had some personal reason for selling Christianity. There were the social-but- terfly people, who loved meeting new faces. Sharing Christ was a great excuse for them to engage with anyone,anywhere. Some people had a herd personality — they felt comfortable only in a like-minded crowd. They had to convince others to believe in order to feel secure about their own beliefs. Other people had a savior personality — they needed to rescue someone. These people did evangelism because of the great feeling of being needed. Last but not least, there were the enthusiastic people, who were often the newest people. They wanted to talk about the good news and good times to keep themselves upbeat and stoke the fire of their enthusiasm.”

“May we be excused?” Charlotte said, spotting an opening in the conversation. Kenneth’s chair was already empty, but Jack could hear faint truck noises coming from beneath it.

“Of course,” Byron said. “Play in the lounge for a while until we’re ready for the family meeting.” Kenneth raced out of the room; Charlotte took her dishes into the kitchen.

Jack returned to his line of questioning. “So, if I

understand correctly,” he said, “selling is not the answer

— it only works for the five percent who are wired to act that way. It doesn’t work for the majority of Christians.”

“Correct.”

“So what’s the alternative?” Jack asked. “In my inter- views I get the feeling it has something to do with being open about your life, or with being friendly — but I can’t seem to put my finger on it.”

Byron thought about an answer. “It’s not quite that simple. In recent years, something called friendship evan- gelism has become quite popular, and it utilizes friendliness and openness. But it the end, it is often a set-up for the sell. Instead of hitting up a stranger with a gospel presentation, you befriend the person — to soften up your potential buyer — before you unleash the sales pitch.”

“OK, fine,” Jack said wearily. “But that still doesn’t tell me what the alternative is. If these other methods don’t work, what’s your method?”

“No method at all,” Byron said. He smiled broadly. “I don’t mean to be evasive with you, but this didn’t start with me trying to figure out how to get evangelism going in our church. I never developed a curriculum or appoint- ed a committee to discuss the matter. What happened is simply that my life was transformed by God.”

He paused to finish the rest of his juice. “You see, my father and I fought constantly when I was growing up, and by the time I was eighteen I had moved out and barely looked back. Then my mother was diagnosed with cancer, and was given only a few weeks to live. I moved back into their house to help care for her, and a friend of mine — who became something of a mentor later on — suggest- ed that this was my opportunity to heal my relationship with my father.

“I wasn’t sure where to begin, or even if I wanted to begin at all, but this mentor suggested that my father and I take turns reading Psalms to my mum to comfort her. I didn’t think he’d go for it, and I didn’t think a few Bible verses were going to change anything between us. But he said yes. And before long it became impossible for me to hear those words of peace, and even the words of anger in some parts, coming from my father’s lips and not begin to see that he was every bit as human as I was. And the wall between us just fell.” Byron’s lips trembled slightly. “I had thought the plan was to get him to change, but my mentor knew that we just needed God as a liaison between us.”

Sue took over the story, having obviously heard it hundreds of times before. “You wouldn’t believe the dif- ference that made when he was talking to people. It was no longer ‘you need this’ or ‘you should do that.’ It was,

‘God has made a difference in my life.’ We were used to talking about the Bible as the source of all truth, but then it became ‘The Bible helped heal me.’”

Byron had regained his composure. “The point is that sharing the good news has less to do with what I do to people — some presentation, some argument — and more to do with what I am doing in my own relationship with God, and whether that’s worth copying. It has to do with the practices and habits in my marriage and my fam- ily that put God at the center of my relationships and bring us close together. Is my Christian life worth repli- cating?”

Jack wiped his mouth with a napkin. “I can see how that approach is different from selling,” he acknowledged, “but it seems that you’d get maybe one percent of people following that course, not one hundred. You’d really have to have your act together before you could talk to any- body.”

Byron shook his head. “You’re still thinking of Christianity as a program to join, or as a system of thought to adopt,” he said. “It’s more like fishing for you and me — we might not be the best at it, we might not know all there is to know, but we love it. We’d love to teach others to love it, too. Christianity is just one of those things I love. I love God; I love how He’s changed me; I love hearing how God interacts with other people. That’s the atmosphere we have at our church. That’s the kind of culture we cultivate. The evangelism is just a natural by- product of that.”

Sue murmured her assent. “You see, if Christianity is something that is making a meaningful difference in your daily life, then average Christians will be able to get oth- ers excited about it. They won’t be able to help it. But if Christianity is not making much of a difference in the lives of average people, then you have to constantly prop it up with marketing and selling.”

Something clicked in Jack’s head; he began to see a single thread linking all the stories that people had told him about their lives. They had all described an old life and then a new life. He smiled, glad to feel his intuition had not completely left him. “So your movement is driv- en by the engine of personal transformation.”

Byron thought this over. “I suppose you could put it that way. It’s the spark, at least, for getting the thing mov- ing.” He smiled. “Of course, without God at the steering wheel, it wouldn’t move at all.”

“Of course,” Jack said, and returned the smile, although truthfully he was reluctant to assign God a role in any of this.

Charlotte came back into the dining room and asked if her parents were ready for the family meeting yet.

“Actually, we’re running a little late,” Byron said as he looked

at his watch. He asked Sue to set up for

the meet- ing while he and Jack cleared dishes.

Jack followed Byron into the kitchen with a stack of dirty plates. “I don’t have to be here for this if you’d rather have family time alone,” he offered.

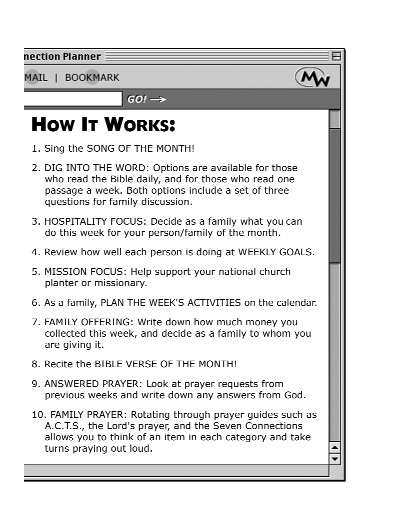

“Nonsense,” Byron said. “We invited you to our home not only to answer your questions about the move- ment, but to show you how it works. You did get the web- site address with the family-meeting pages, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” he said, “although I didn’t really understand what they were for.”

“Then let me show you,” Byron said, and ushered him into the lounge.

Sue was on the couch, tuning a guitar, and the two children were sitting on the carpet. Byron joined his wife, and Jack remained standing in the doorway to watch the group.

Sue invited Jack to sing along with their song of the month, which was “Amazing Grace.” He didn’t know the words well enough to join in, but he enjoyed listening to the family’s surprisingly melodic voices; it had been many years since he’d heard the familiar tune.

As the Edwards family moved on to reading a Bible passage and answering questions about it, Jack found himself tuning out the conversation and just taking in the happy interaction. He was homesick for his children already, but this made him wonder what kind of people he was raising his kids to become. He was always taking them to fun places on the weekends when he saw them— probably to compensate for being away so much — but was he anything more to them than fun? What was he teaching them? Were they learning anything about life from him?

By the time Jack roused himself out of his thoughts, the group had moved on to discuss their mission focus for the week. Apparently they supported an African church planter, and the kids decided they wanted to make a card for him. As Byron brought out construction paper, crayons, and glitter, Jack decided he wanted to be part of this. He joined the kids on the ground and helped them with the glue stick.

An hour flew by as the family members gave out stickers for how well each person had done at chores, chose a person to be their hospitality focus next week, gathered coins and notes for a family offering, planned their activities for next week on the calendar, and made a list of the prayers God had answered for them.

Jack had felt comfortable throughout most of the meeting, but when they ended the evening by praying to God, he felt suddenly excluded again. God was OK as a topic of conversation, or even as a Higher Power that helped you out, but talking to this God person just seemed like hocus-pocus. If He was God of the Universe, He wouldn’t be hanging on humans’ every word, would He?

After the meeting, Sue took the kids upstairs to bed, and Byron led Jack into the kitchen for some tea and cake.

“So what did you think?” Byron asked.

“It was fun — a lot of good activities,” Jack said. “But, to be honest ... I didn’t see what it has to do with the movement.”

“Well, it’s simple, really. Our family meets like this every week. Our neighbors on either side meet, too. The staff at my church all meet with their families. In fact, the majority in my church have joined in — singles and cou- ples make their own groups or join with nearby families and participate, too. We often gather as a large group to sing our songs or join together on a hospitality project. Our church gives special recognition to families that don’t miss a meeting for a whole year. The family meetings are just part of our culture.”

Jack stirred a little more sugar into his tea. “You’ve mentioned this culture thing a few times now, but I don’t quite understand what you mean by it.”

Byron nodded. “Take England, for instance,” he said. “Our culture is very similar to yours in America, but you can definitely tell the difference when you’re over here — the words we use, the way we drive, what we eat.”

“Actually, I enjoy those little differences quite a lot,” Jack said, smiling. “I feel like I’m fitting in a little when I say ‘take away’ in a restaurant instead of ‘to go.’ It’s like a little game.”

“Exactly. These minor differences are what give a culture its character, its personality. In my church’s cul- ture, we all have these family meetings. We have a culture of prayer. We have a culture of getting into the Bible — and, in turn, the Bible helps us further create culture. We have a culture of singing, of hospitality, of generosity. That’s what it means to be part of our community.”

“So you try to attract people with these little distinctions?” Jack asked.

“Well, I like to think that their primary purpose is to strengthen and enrich the lives of our members.” Byron munched on a tea cake. “But, yes, we do want our culture to be attractive. We do make an effort to create an appeal- ing community. Because in the end you can never accept only Christ — you have to accept Him and His family.

“A lot of evangelism is geared toward accepting a particular message or a particular belief, not a particular people. But you can’t embrace God without embracing His people. It’s like when my brother fell in love with an Indian woman in college. At first he was thinking just about her personality and her charm, but before long he realized he was getting himself involved with a whole new culture, a whole new set of rules and expectations, and a whole new set of people. Fortunately for him, he found this culture interesting, and now the woman is my sister- in-law. We hope to make our community interesting and attractive for the same reason — to draw others into it.”

Byron sipped the last of his tea and continued. “The fact is, our church has no evangelism committee, no mar- keting department, no budget for tracts or literature. We do no real work on evangelism at all. We put all the real work into the culture, making it alive and powerful and binding. We make it into a breeding ground for changed lives. And we measure how well we’re doing by how will- ing people are to share their walk with God. If our culture is really plugging people into a vibrant relationship with God, they’ll talk about it. Word will spread. Evangelism will happen quite naturally.”

Jack soaked

in Byron’s words.

At last, it made sense why he’d scarcely heard the word

“evangelism”

since he arrived in England. No one

here fretted about it; it was

a natural by-product of

vigilantly putting God at the center of everything

in life.

Sue returned from upstairs and joined the men at the table. The children, apparently, had not wanted to go to sleep, and the conversation turned toward the frustrating yet adorable things that kids will do to evade responsibil- ities. Jack laughed as he shared some of his favorite sto- ries about Scott and Bethy, although, in truth, his family arrangement made those moments bittersweet.

The evening grew late, and Jack decided to excuse himself. As Byron walked him to the door, Jack tossed out a last question. “By the way, when does your next church service take place? I’d like to take one in firsthand.”

Byron just smiled. “I’m sure you’ve already been to one of our church gatherings.”

“No,” Jack corrected. “I’ve never even been to your building.”

“That wouldn’t be necessary,” Byron said, shrugging. “We’re not really a church that packs people into an arena. We have multiple, loosely connected things hap- pening all over the city. You’ve probably wandered into one or two.”

“Really?”

“Sure. There’s actually a whole network of churches and gatherings that have spun from what we originally started. There are probably a hundred thousand people connected in some way to what we do.”

“A hundred thousand?” Jack said, quite surprised.

Byron shrugged again. “Don’t get the wrong idea —

it’s not like I’m actually in charge of that many people. I don’t set the agenda for everyone, I just help coordinate everyone’s efforts.”

“Still — you said there were fifty or sixty people in your church ten years ago. That’s incredible growth. Almost unbelievable, to tell you the truth.”

“No, not really,” Byron said, waving away the sug- gestion. “It may sound like a lot, but I don’t think you understand how fast the good news can spread. Let’s say it takes me an entire year to reach just one person. And the next year, each of us reaches just one more person apiece. At that pace, it takes only twenty years to reach a million people. In thirty years, the whole planet would be covered.”

Jack shook his head in disbelief. “You make chang- ing the world sound almost routine.”

Byron laughed. “Pardon my nonchalance,” he said. “I suppose if I felt I was responsible for the size of our church, I might be a little more impressed. But it’s God’s doing. And I know it’s just the very start of what He has got in store.”

Jack stared blankly. “Even considering that He’s allowed Christianity to take 2,000 years to travel once around the globe?

“Ideas and beliefs always traveled slowly in the past,” Byron said matter-of-factly. “There was little inter- action between one nationality and another. Language barriers and prejudices kept people at arm’s length.

Economic reality kept you in the same town you were raised in, and rigid social classes kept you from talking to half the people there. But in the last hundred years, barriers have fallen. We stay in touch with people all over the country and all over the world. Even though there are far more people these days, the planet is connected by just six degrees of separation.”

“Doesn’t that have something to do with Kevin

Bacon?” Jack interrupted. “Sorry?”

“Oh,” Jack said lamely. “I heard about this game called ‘Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon’ — movie fans try to link the actor to any other actor through six films or less.” “Interesting,” Byron said. “Well, what I’m talking about is similar in principle but of much more impor- tance. It states that we’re all just six relationships away from anyone else on earth. Free trade, air travel, media coverage, and computers have broken down boundaries between us. We’ve been linked together in a vast net-

work.”

Jack shifted his weight onto his other foot. “And this networked world is somehow better for spreading Christianity?” he asked.

“Not automatically,” Byron said. He gestured back toward the lounge and invited Jack to sit down again. “In many ways, the networked world has created more hur- dles for Christianity. Now that our circle of friends extends far beyond our neighborhoods, the church is no longer the default social and cultural center of town. New diversions and entertainments mean that it’s harder to entice people under our roof. The typical church response has been to try to keep up with the competition. Especially in America, I’ve noticed, they’ve been building gymnasiums and softball fields, classrooms and auditoriums to keep the interest of those who like athletics, singing, intellectual study, and socializing. They’re offering specialized pro- grams for kids, families, men, women, couples, singles, teens, and the retired. But the fact is, no matter how hard Christians try, we can’t compete with Hollywood for the best entertainment, with community centers for the best sports and crafts, or with vast libraries of books for the best spiritual insights.

“But in the movement, we make use of the net- worked world rather than fighting it. Instead of trying to bring the whole world under our roof to give them the good news, our church brings the good news wherever our people go — into neighborhoods, workplaces, sports programs, community activities, families — from one per- son, one couple, one family to another. The good news spreads across the network of humanity like a positive computer virus, infecting one person after another with the love of God.”

Jack leaned back in his chair, absorbing Byron’s words. This idea of a network gave a kind of structure to what he’d believed was a lot of random activity. It fit his research perfectly — people affecting people rather than disseminating some program.

“That’s a great image,” Jack said. “In a way, that’s how I eventually discovered you — I followed the invisible threads of connection between people and found that a great number of them plugged in directly to you.”

Byron waved the thought away. “I know this will sound like false modesty, but the network is much deep- er than me. And I can trace my own spiritual influence back through a chain of at least eight people. Who knows if these threads of connection go back even further, or where they all converge?”

Jack was surprised by how deeply this thing went. It really seemed to be a grassroots kind of effort. “Do you think I can get in touch with that eighth person in your chain?” he asked, casting his hook for an interview.

Byron yawned. “I don’t know — it was several years ago when I last saw him. I’m not sure I even have his number anymore.”

Jack nodded, expecting as much. It was just as well; he had enough good information from this evening to begin putting together his article. If things went well this week, he might make it home for spring break after all.

"...last place on earth I’d expect to see this happening,” says Pithers. “You have to understand: Our famous British reserve and polite for- mality should have nipped this thing in the bud. People here just don’t go around talking about their marriage problems or their per- sonal struggles. Or, at least, they didn’t used to.”

Dr. Bertenshaw also struggles to understand. “I would sooner have expected people to start weaving tapestries or donning suits of armor than for the Church of England to be showing so much life. Don’t get me wrong — people here have always taken an interest in church, but mostly within the context of our heritage and identity as British citizens. I always expected it to stay there.”

However, despite the obstacles of sedentary tradition and proper manners, the church movement is growing exponentially. London is perhaps the epicenter of this quake, but reverberations are felt as far away as Exeter, Shrewsbury, and Newcastle, not to mention conti- nental cities like Brussels and Paris.

The key to success seems to lie in the power of a changed life. “Once your life has been transformed,” says Rita Fairbanks, West Yorkshire resident, “you want to share it. Once your family has been transformed, you want to share it. Two years ago I used to fight with my daughter constantly; now I have a natural bridge to help other struggling parents. What am I supposed to do, just keep silent?”

With more than a million other enthusiasts thinking the same thing, England is poised to become a very loud place indeed. The only question is: Will their magic continue to change lives, or will the clock strike midnight on this Cinderella tale?"