Reading: Jonathan Edwards

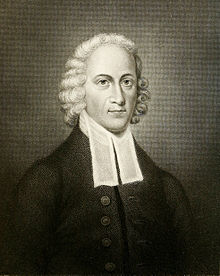

Jonathan Edwards (October 5, 1703 – March 22, 1758) was a North American revivalist preacher, philosopher, and congregationalist protestant theologian. Edwards is widely regarded as one of the America's most important and original philosophical theologians. Edwards' theological work is broad in scope, but he was rooted in Reformed theology, the metaphysics of theological determinism, and the Puritan heritage. Recent studies have emphasized how thoroughly Edwards grounded his life's work on conceptions of beauty, harmony, and ethical fittingness, and how central The Enlightenment was to his mindset.[3] Edwards played a critical role in shaping the First Great Awakening and oversaw some of the first revivals in 1733–35 at his church in Northampton, Massachusetts.[4][5] His theological work gave rise to a distinct school of theology known as the New England theology.

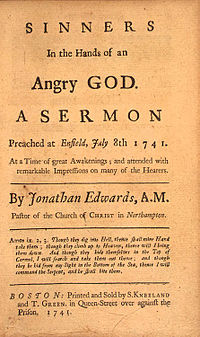

Edwards delivered the sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God", a classic of early American literature, during another revival in 1741, following George Whitefield's tour of the Thirteen Colonies.[6] Edwards is well known for his many books, The End For Which God Created the World, The Life of David Brainerd, which inspired thousands of missionaries throughout the 19th century, and Religious Affections, which many Reformed Evangelicals still read today.[7] Edwards died from a smallpox inoculation shortly after beginning the presidency at the College of New Jersey (Princeton).[8] He was the grandfather of Aaron Burr,[1] third Vice President of the United States.

Contents

Biography

Early life

Jonathan Edwards was born on October 5, 1703, and was the son of Timothy Edwards (1668–1759), a minister at East Windsor, Connecticut (modern-day South Windsor), who eked out his salary by tutoring boys for college. His mother, Esther Stoddard, daughter of the Rev. Solomon Stoddard, of Northampton, Massachusetts, seems to have been a woman of unusual mental gifts and independence of character.[9][page needed] Jonathan, their only son, was the fifth of 11 children. He was trained for college by his father and elder sisters, all of whom received an excellent education and one of whom, Esther, the eldest, wrote a semi-humorous tract on the immateriality of the soul, often mistakenly attributed to Jonathan.[10]

He entered Yale College in 1716, at just under the age of 13. In the following year, he became acquainted with John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, which influenced him profoundly. During his college studies, he kept notebooks labeled "The Mind," "Natural Science" (containing a discussion of the atomic theory), "The Scriptures" and "Miscellanies," had a grand plan for a work on natural and mental philosophy, and drew up for himself rules for its composition. He was interested in natural history, and as a precocious 11-year-old, observed and wrote an essay detailing the ballooning behavior of some spiders. Edwards would edit this text to match the burgeoning genre of scientific literature, and his "The Flying Spider" fit easily into the then-current scholarship on spiders.[11][12]

Even though he would go on to study theology for two years after his graduation, Edwards continued to be interested in science. However, while many European scientists and American clergymen found the implications of science pushing them towards deism, Edwards went the other way, and saw the natural world as evidence of God's masterful design, and throughout his life, Edwards often went into the woods as a favorite place to pray and worship in the beauty and solace of nature.[13]

Edwards was fascinated by the discoveries of Isaac Newton and other scientists of his age. Before he undertook full-time ministry work in Northampton, he wrote on various topics in natural philosophy, including flying spiders, light, and optics. While he was worried about the materialism and faith in reason alone of some of his contemporaries, he saw the laws of nature as derived from God and demonstrating his wisdom and care. Edwards also wrote sermons and theological treatises that emphasized the beauty of God and the role of aesthetics in the spiritual life, in which he anticipates a 20th-century current of theological aesthetics, represented by figures like Hans Urs von Balthasar.

In 1722 to 1723, he was for eight months "stated supply" (a clergyman employed to supply a pulpit for a definite time, but not settled as a pastor) of a small Presbyterian Church in New York City. The church invited him to remain, but he declined the call. After spending two months in study at home, in 1724–26, he was one of the two tutors at Yale, earning for himself the name of a "pillar tutor", from his steadfast loyalty to the college and its orthodox teaching, at the time when Yale's rector, Timothy Cutler, his tutor Daniel Brown, his former tutor Samuel Johnson, and four local ministers, had declared for the Anglican Church.[9][

The years 1720 to 1726 are partially recorded in his diary and in the resolutions for his own conduct which he drew up at this time. He had long been an eager seeker after salvation and was not fully satisfied as to his own conversion until an experience in his last year in college, when he lost his feeling that the election of some to salvation and of others to eternal damnation was "a horrible doctrine," and reckoned it "exceedingly pleasant, bright and sweet." He now took a great and new joy in taking in the beauties of nature and delighted in the allegorical interpretation of the Song of Solomon. Balancing these mystic joys is the stern tone of his Resolutions, in which he is almost ascetic in his eagerness to live earnestly and soberly, to waste no time, to maintain the strictest temperance in eating and drinking.

[14] On February 15, 1727, Edwards was ordained minister at Northampton and assistant to his grandfather Solomon Stoddard. He was a scholar-pastor, not a visiting pastor, his rule being 13 hours of study a day.

In the same year, he married Sarah Pierpont. Then 17, Sarah was from a storied New England clerical family: her father was James Pierpont (1659–1714), the head founder of Yale College, and her mother was the great-granddaughter of Thomas Hooker.[15] Sarah's spiritual devotion was without peer, and her relationship with God had long proved an inspiration to Edwards. He first remarked on her great piety when she was 13 years old.[16] She was of a bright and cheerful disposition, a practical housekeeper, a model wife and the mother of his 11 children, who included Esther Edwards. Solomon Stoddard died on February 11, 1729, leaving to his grandson the difficult task of the sole ministerial charge of one of the largest and wealthiest congregations in the colony, and one proud of its morality, its culture and its reputation.[9][page needed] Edwards, as with all of the Reformers and Puritans of his day, held to complementarian views of marriage and gender roles.[17]

Great Awakening

The revival gave Edwards an opportunity for studying the process of conversion in all its phases and varieties, and he recorded his observations with psychological minuteness and discrimination in A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton (1737). A year later, he published Discourses on Various Important Subjects, the five sermons which had proved most effective in the revival, and of these, none was so immediately effective as that on the Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners, from the text, "That every mouth may be stopped." Another sermon, published in 1734, A Divine and Supernatural Light, Immediately Imparted to the Soul by the Spirit of God, set forth what he regarded as the inner, moving principle of the revival, the doctrine of a special grace in the immediate, and supernatural divine illumination of the soul.[19]On July 8, 1731,[18] Edwards preached in Boston the "Public Lecture" afterward published under the title "God Glorified in the Work of Redemption, by the Greatness of Man's Dependence upon Him, in the Whole of It," which was his first public attack on Arminianism. The emphasis of the lecture was on God's absolute sovereignty in the work of salvation: that while it behooved God to create man pure and without sin, it was of his "good pleasure" and "mere and arbitrary grace" for him to grant any person the faith necessary to incline him or her toward holiness, and that God might deny this grace without any disparagement to any of his character. In 1733, a Protestant revival began in Northampton and reached an intensity in the winter of 1734 and the following spring, that it threatened the business of the town. In 6 months, nearly 300 of 1100 youths were admitted to the church.

By 1735, the revival had spread and popped up independently across the Connecticut River Valley, and perhaps as far as New Jersey. However, criticism of the revival began, and many New Englanders feared that Edwards had led his flock into fanaticism.[20] Over the summer of 1735, religious fervor took a dark turn. A number of New Englanders were shaken by the revivals but not converted and became convinced of their inexorable damnation. Edwards wrote that "multitudes" felt urged—presumably by Satan—to take their own lives.[21] At least two people committed suicide in the depths of their spiritual distress, one from Edwards's own congregation—his uncle Joseph Hawley II. It is not known if any others took their own lives, but the "suicide craze"[22] effectively ended the first wave of revival, except in some parts of Connecticut.[23]

However, despite these setbacks and the cooling of religious fervor, word of the Northampton revival and Edwards's leadership role had spread as far as England and Scotland. It was at this time that Edwards was acquainted with George Whitefield, who was traveling the Thirteen Colonies on a revival tour in 1739–40. The two men may not have seen eye to eye on every detail. Whitefield was far more comfortable with the strongly emotional elements of revival than Edwards was, but they were both passionate about preaching the Gospel. They worked together to orchestrate Whitefield's trip, first through Boston and then to Northampton. When Whitefield preached at Edwards's church in Northampton, he reminded them of the revival they had experienced just a few years before.[24] This deeply touched Edwards, who wept throughout the entire service, and much of the congregation too was moved.

Revival began to spring up again, and Edwards preached his most famous sermon "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God", in Enfield, Connecticut in 1741. Though this sermon has been widely reprinted as an example of "fire and brimstone" preaching in the colonial revivals, this is not in keeping with Edward's actual preaching style. Edwards did not shout or speak loudly, but talked in a quiet, emotive voice. He moved his audience slowly from point to point, towards an inexorable conclusion: they were lost without the grace of God. While most 21st-century readers notice the damnation looming in such a sermon text, historian George Marsden reminds us that Edwards' was not preaching anything new or surprising: "Edwards could take for granted... that a New England audience knew well the Gospel remedy. The problem was getting them to seek it.".[25]

The movement met with opposition from conservative Congregationalist ministers. In 1741, Edwards published in its defense The Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God, dealing particularly with the phenomena most criticized: the swoonings, outcries, and convulsions. These "bodily effects," he insisted, were not distinguishing marks of the work of the Spirit of God one way or another; but so bitter was the feeling against the revival in the more strictly Puritan churches, that in 1742, he was forced to write a second apology, Thoughts on the Revival in New England, where his main argument concerned the great moral improvement of the country. In the same pamphlet, he defends an appeal to the emotions, and advocates preaching terror when necessary, even to children, who in God's sight "are young vipers... if not Christ's."

He considers "bodily effects" incidental to the real work of God, but his own mystic devotion and the experiences of his wife during the Awakening (which he gives in detail) make him think that the divine visitation usually overpowers the body, a view in support of which he quotes Scripture. In reply to Edwards, Charles Chauncy wrote Seasonable Thoughts on the State of Religion in New England in 1743 and anonymously penned The Late Religious Commotions in New England Considered in the same year. In these works, he urged conduct as the sole test of conversion, and the general convention of Congregational ministers in the Province of Massachusetts Bay protested "against disorders in practice which have of late obtained in various parts of the land." In spite of Edwards's able pamphlet, the impression had become widespread that "bodily effects" were recognized by the promoters of the Great Awakening as the true tests of conversion.

To offset this feeling, Edwards preached at Northampton, during the years 1742 and 1743, a series of sermons published under the title of Religious Affections (1746), a restatement in a more philosophical and general tone of his ideas as to "distinguishing marks." In 1747, he joined the movement started in Scotland called the "concert in prayer," and in the same year published An Humble Attempt to Promote Explicit Agreement and Visible Union of God's People in Extraordinary Prayer for the Revival of Religion and the Advancement of Christ's Kingdom on Earth. In 1749, he published a memoir of David Brainerd who had lived with his family for several months and had died at Northampton in 1747. Brainerd had been constantly attended by Edwards's daughter Jerusha, to whom he was rumored to have been engaged to be married, though there is no surviving evidence of this. In the course of elaborating his theories of conversion, Edwards used Brainerd and his ministry as a case study, making extensive notes of his conversions and confessions.

Later years

While Edwards owned slaves[26] for most of his adult life, he did experience a change of heart[27] in regards to the Atlantic slave trade. Though he purchased a newly imported slave named Venus in 1731, Edwards later denounced the practice of importing slaves from Africa in a 1741 pamphlet.[28]

After being dismissed from the pastorate, he ministered to a tribe of Mohican Indians in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In 1748, there had come a crisis in his relations with his congregation. The Half-Way Covenant, adopted by the synods of 1657 and 1662, had made baptism alone the condition to the civil privileges of church membership, but not of participation in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper. Edwards's grandfather and predecessor in the pastorate, Solomon Stoddard, had been even more liberal, holding that the Supper was a converting ordinance and that baptism was a sufficient title to all the privileges of the church.

As early as 1744, Edwards, in his sermons on Religious Affections, had plainly intimated his dislike of this practice. In the same year, he had published in a church meeting the names of certain young people, members of the church, who were suspected of reading improper books, and also the names of those who were to be called as witnesses in the case. It has often been reported that the witnesses and accused were not distinguished on this list, and so the entire congregation was in an uproar. However, Patricia Tracy's research has cast doubt on this version of the events, noting that in the list he read from, the names were definitely distinguished. Those involved were eventually disciplined for disrespect to the investigators rather than for the original incident. In any case, the incident further deteriorated the relationship between Edwards and the congregation.[29]

Edwards's preaching became unpopular. For four years, no candidate presented himself for admission to the church, and when one eventually did, in 1748, he was met with Edwards's formal tests as expressed in the Distinguishing Marks and later in Qualifications for Full Communion, 1749. The candidate refused to submit to them, the church backed him, and the break between the church and Edwards was complete. Even permission to discuss his views in the pulpit was refused. He was allowed to present his views on Thursday afternoons. His sermons were well attended by visitors, but not his own congregation. A council was convened to decide the communion matter between the minister and his people. The congregation chose half the council, and Edwards was allowed to select the other half of the council. His congregation, however, limited his selection to one county where the majority of the ministers were against him. The ecclesiastical council voted that the pastoral relation be dissolved.

The church members, by a vote of more than 200 to 23, ratified the action of the council, and finally a town meeting voted that Edwards should not be allowed to occupy the Northampton pulpit, though he continued to live in the town and preach in the church by the request of the congregation until October 1751. In his "Farewell Sermon" he preached from 2 Corinthians 1:14 and directed the thoughts of his people to that far future when the minister and his people would stand before God. In a letter to Scotland after his dismissal, he expresses his preference for Presbyterian to congregational polity. His position at the time was not unpopular throughout New England. His doctrine that the Lord's Supper is not a cause of regeneration and that communicants should be professing Protestants has since (largely through the efforts of his pupil Joseph Bellamy) become a standard of New England Congregationalism.

Edwards was in high demand. A parish in Scotland could have been procured, and he was called to a Virginia church. He declined both, to become in 1751, pastor of the church in Stockbridge, Massachusetts and a missionary to the Housatonic Indians, taking over for the recently deceased John Sergeant. To the Indians, he preached through an interpreter, and their interests he boldly and successfully defended by attacking the whites who were using their official positions among them to increase their private fortunes. During this time he got to know Judge Joseph Dwight who was Trustee of the Indian Schools.[30] In Stockbridge, he wrote the Humble Relation, also called Reply to Williams (1752), which was an answer to Solomon Williams (1700–76), a relative and a bitter opponent of Edwards as to the qualifications for full communion. He there composed the treatises on which his reputation as a philosophical theologian chiefly rests, the essay on Original Sin, the Dissertation Concerning the Nature of True Virtue, the Dissertation Concerning the End for which God created the World, and the great work on the Will, written in four and a half months, and published in 1754 under the title, An Inquiry into the Modern Prevailing Notions Respecting that Freedom of the Will which is supposed to be Essential to Moral Agency.

Aaron Burr, Sr., Edwards' son-in-law, died in 1757 (he had married Esther Edwards five years before, and they had made Edwards the grandfather of Aaron Burr, later Vice President of the United States). Edwards felt himself in "the decline of life", and inadequate to the office, but was persuaded to replace Burr as president of the College of New Jersey. He arrived in January and was installed on February 16, 1758. He gave weekly essay assignments in theology to the senior class.[31] Almost immediately after becoming president, Edwards, a strong supporter of smallpox inoculations, decided to get inoculated himself in order to encourage others to do the same. Unfortunately, never having been in robust health, he died as a result of the inoculation on March 22, 1758. He is buried in Princeton Cemetery. Edwards had three sons and eight daughters.

Legacy

The followers of Jonathan Edwards and his disciples came to be known as the New Light Calvinist ministers, as opposed to the traditional Old Light Calvinist ministers. Prominent disciples included the New Divinity school's Samuel Hopkins, Joseph Bellamy and Jonathan Edwards's son Jonathan Edwards Jr., and Gideon Hawley. Through a practice of apprentice ministers living in the homes of older ministers, they eventually filled a large number of pastorates in the New England area. Many of Jonathan and Sarah Edwards's descendants became prominent citizens in the United States, including the Vice President Aaron Burr and the College Presidents Timothy Dwight, Jonathan Edwards Jr. and Merrill Edwards Gates. Jonathan and Sarah Edwards were also ancestors of First Lady of the United States Edith Roosevelt, the writer O. Henry, the publisher Frank Nelson Doubleday and the writer Robert Lowell.

Edwards's writings and beliefs continue to influence individuals and groups to this day. Early American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missionsmissionaries were influenced by Edwards's writings, as is evidenced in reports in the ABCFM's journal "The Missionary Herald," and beginning with Perry Miller's seminal work, Edwards enjoyed a renaissance among scholars after the end of the Second World War. The Banner of Truth Trust and other publishers continue to reprint Edwards's works, and most of his major works are now available through the series published by Yale University Press, which has spanned three decades and supplies critical introductions by the editor of each volume. Yale has also established the Jonathan Edwards Project online. Author and teacher, Elisabeth Woodbridge Morris, memorialized him, her paternal ancestor (3rd great grandfather) in two books, The Jonathan Papers(1912), and More Jonathan Papers (1915). In 1933, he became the namesake of Jonathan Edwards College, the first of the 12 residential colleges of Yale, and The Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University was founded to provide scholarly information about Edwards' writings. In 2009, a classical Protestant school was founded in Nashville, TN bearing his name and dedicated to memorializing Edwards' example of fervent piety and rigorous academics: Jonathan Edwards Classical Academy.[32]Edwards is remembered today as a teacher and missionary by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on March 22. The contemporary poet Susan Howe frequently describes the composition of Edwards' manuscripts and notebooks held at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in a number of her books of poetry and prose, including Souls of the Labadie Tract, 2007 and That This, 2010. She notes how some of Edwards' notebooks were hand sewn from silk paper that his sisters and wife used for making fans.[33] Howe also argues in My Emily Dickinson that Emily Dickinson was formatively influenced by Edwards's writings, and that she "took both his legend and his learning, tore them free from his own humorlessness and the dead weight of doctrinaire Calvinism, then applied the freshness of his perception to the dead weight of American poetry as she knew it."[34]

Most recently, Edwards' texts are also studied with the use of digital methods. Scholars from the Institute of English Studies at the Jagiellonian University have applied stylometry to establish stylistic connections between different groups of Edwards' sermons.[35] Similarly, Rob Boss from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary has used visual graphics software to explore the conceptual connections between Scripture and Nature in the theology of Edwards.[36]

Progeny[edit]

The eminence of many descendants of Edwards led some Progressive Era scholars to view him as proof of eugenics(of course he died at 54).[37][38][39] Upon American culture, his descendants have had a disproportionate effect: his biographer George Marsden notes that "the Edwards family produced scores of clergymen, thirteen presidents of higher learning, sixty-five professors, and many other persons of notable achievements."[40]

Works

The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University holds the majority of Edwards' surviving manuscripts, including over one thousand sermons, notebooks, correspondence, printed materials, and artifacts.[41] Two of Edwards' manuscript sermons, a 1737 letter to Mrs. Hannah Morse, and some original minutes of a town meeting in Northampton are held by The Presbyterian Historical Society in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[42]

The entire corpus of Edwards' works, including previously unpublished works, is available online through the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale University website.[43] The Works of Jonathan Edwards project at Yale has been bringing out scholarly editions of Edwards based on fresh transcriptions of his manuscripts since the 1950s; there are 26 volumes so far. Many of Edwards' works have been regularly reprinted. Some of the major works include:

- Charity and its Fruits.

- Protestant Charity or The Duty of Charity to the Poor, Explained and Enforced. 1732. online text at Bible Bulletin Board

- A Dissertation Concerning the End for Which God Created the World

- Contains Freedom of the Will and Dissertation on Virtue, slightly modified for easier reading.

- Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the Spirit of God.

- A Divine and Supernatural Light, Immediately Imparted to the Soul by the Spirit of God (1734).

- A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton

- The Freedom of the Will

- A History of the Work of Redemption including a View of Church History

- The Life and Diary of David Brainerd, Missionary to the Indians.

- The Nature of True Virtue

- Original Sin.

- Some Thoughts Concerning the Present Revival in New England and the Way it Ought to be Acknowledged and Promoted.

- Religious Affections

Sermons

The text of some of many of Edwards's sermons have been preserved, some are still published and read today among general anthologies of American literature. Among his more well-known sermons are:[44]

- "The Justice of God in the Damnation of Sinners"

- "The Manner of Seeking Salvation"

- "Pressing into the Kingdom of God"

- "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God"

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Biography". Edwards Center. Yale University. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 93–95, 105–12, 242–49, 607.

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 34–41.

- ^ First Churches

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 150–63.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 214–26.

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 499.

- ^ "Jonathan Edwards at the College of New Jersey" (exhibit). Princeton University. Archived from the original on December 24, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marsden 2003.

- ^ Kenneth P. Minkema, "The Authorship of 'The Soul,'" duke University Library Gazette 65 (October 1990):26–32.

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 66.

- ^ David S. Wilson, "The Flying Spider," Journal of the History of Ideas 32, no. 3 (Jul–Sep 1971): 447–458.

- ^ Jonathan Edwards (1840). The works of Jonathan Edwards, A.M. p. 54.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 51.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 87, 93.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 93–95, 95–100, 105–9, 241–42.

- ^ "Marriage to a Difficult Man", by Elisabeth Dodd 1971

- ^ "Edwards – God Glorified in Man's Dependence". Monergism.com. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Jonathan, Edwards; Reiner, Smolinski (October 15, 2017). "A Divine and Supernatural Light, Immediately imparted to the Soul by the Spirit of God, Shown to be both a Scriptural, and Rational Doctrine". Electronic Texts in American Studies. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 161-2.

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 168.

- ^ Marsden 2003; Marsden uses the phrase "suicide craze" twice (pp. 168, 541).

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 163–69.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 206–12.

- ^ Marsden 2003, p. 224.

- ^ Sweeney, Douglas A. (March 23, 2010). Jonathan Edwards and the Ministry of the Word: A Model of Faith and Thought. InterVarsity Press. pp. 66–68. ISBN 9780830879410.

they owned several slaves. Beginning in June 1731, Edwards joined the slave trade, buying 'a Negro Girle named Venus ages Fourteen years or thereabout' in Newport, at an auction, for 'the Sum of Eighty pounds.'

- ^ Stinson, Susan (April 5, 2012). "The Other Side of the Paper: Jonathan Edwards as Slave-Owner". Valley Advocate. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

In these rough notes, Edwards cited Scripture in defense of slavery

- ^ Minkema, Kenneth P. (2002). "Jonathan Edwards's Defense of Slavery" (PDF). Massachusetts Historical Review (Race & Slavery). 4: 23–59. ISSN 1526-3894.

Edwards defended the traditional definition of slaves as those who were debtors, children of slaves, and war captives; for him, the trade in slaves born in North America remained legitimate.

- ^ Patricia J. Tracy, Jonathan Edwards, pastor: Religion and society in eighteenth-century Northampton (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006).

- ^ "Judge Joseph Dwight", Family tree maker, Genealogy

- ^ Leitch, Alexander (1979), "Jonathan Edwards", A Princeton Companion, Princeton

- ^ Jonathan Edwards Classical Academy, Nashville, TN

- ^ Howe, Susan. "Choir answers to Choir: Notes on Jonathan Edwards and Wallace Stevens". Poetry Daily. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ Howe, Susan (1985). My Emily Dickinson. New York: New Directions Press. p. 51.

- ^ "They study literary style like fingerprints – News – Science & Scholarship in Poland". Scienceinpoland.pap.pl. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "Elemental Theology". Elemental Theology. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Winship, Albert E (1900), Jukes-Edwards: A Study in Education and Heredity, Harrisburg, PA: RL Myers.

- ^ Jukes-Edwards: A Study in Education and Heredity Chapter II to end. R.L. Myers & Co.; Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; 1900.

- ^ Popenoe, Paul; Johnson, Roswell Hill (1920), "Applied Eugenics", Nature, New York, 106 (2676): 161–62, Bibcode:1921Natur.106..752., doi:10.1038/106752a0.

- ^ Marsden 2003, pp. 500–1.

- ^ "Jonathan Edwards Collection". Yale. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "History". PC USA. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ "Edwards Center". Yale. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Edwards, Jonathan. "Revival Sermons". Jonathan Edwards. Retrieved October 15,2017.

References

- Crisp, Oliver. 2016. Jonathan Edwards Among the Theologians. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- Delattre, Roland André. Beauty and Sensibility in the Thought of Jonathan Edwards: An Essay in Aesthetics and Theological Ethics. New Have, CT: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Fiering, Norman. Jonathan Edwards's Moral Thought and Its British Context. Chapel Hill, NC: 1981.

- Gerstner, John H (1991–1993). The Rational Biblical Theology of Jonathan Edwards, in three volumes. Powhatan, VA: Berea Publications.

- ---. Jonathan Edwards: A Mini-Theology. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1987.

- Hatch, Nathan and Harry O. Stout, eds. Jonathan Edwards and the American Experience. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- Holmes, Stephen R. (2000). God of Grace, God of Glory: The Theology of Jonathan Edwards. Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

- Jenson, Robert (1988). America's Theologian. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kimnach, Wilson, Caleb J. D. Maskell, and Kenneth P. Minkema, eds. Jonathan Edwards's 'Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God': A Casebook. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

- Lee, Sang Hyun. The Philosophical Theology of Jonathan Edwards. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Marsden, George M (2003), Jonathan Edwards: A Life, New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-10596-4

- McClenahan, Michael (2012). Jonathan Edwards and Justification by Faith. Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, ISBN 9781409441786

- McDermott, Gerald Robert. One Holy and Happy Society: The Public Theology of Jonathan Edwards. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 1992.

- Murray, Iain H (1987). Jonathan Edwards: A New Biography. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth.

- Parkes, Henry Bamford (1930). Jonathan Edwards, the Fiery Puritan. New York: Minton, Balch & Co.

- Piper, John (2004). A God Entranced Vision of All Things: The Legacy of Jonathan Edwards. New York: Crossway Books.

- Piper, John (1988). God's Passion for His Glory: Living the Vision of Jonathan Edwards. New York: Crossway Books.

- Smith, John E (2005), Lee, Sang Hyun (ed.), Protestant Virtue and Common Morality in The Princeton Companion to Jonathan Edwards, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Stout, Harry S. ed. The Jonathan Edwards Encyclopedia (2017).

- Winslow, Ola Elizabeth. Jonathan Edwards, 1703–1756: A Biography. 1940

- Woo, B. Hoon (2014). "Is God the Author of Sin?—Jonathan Edwards's Theodicy". Puritan Reformed Journal. 6 (1): 98–123.

- Zakai, Avihu. Jonathan Edwards's Philosophy of History: The Reenchantment of the World in the Age of Enlightenment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Princeton University. "Jonathan Edwards at the College of New Jersey (Princeton University)". Archived from the original on December 24, 2012.