Reading: Catholic Church History to 1900.

History of the Catholic Church in the United States

The Catholic Church in the United States began in the colonial era, but most of the Spanish and French influences had faded by 1800. The Catholic Church grew through immigration, especially from Europe (Germany and Ireland at first, and in 1890-1914 from Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe.) In the nineteenth century the Church set up an elaborate infrastructure, based on diocese run by bishops appointed by the pope. Each diocese set up a network of parishes, schools, colleges, hospitals, orphanages and other charitable institutions. Many priests arrived from France and Ireland, but by 1900 Catholic seminaries were producing a sufficient supply of priests. Many young women became nuns, typically working as teachers and nurses. The Catholic population was primarily working-class until after World War II when it increasingly moved into white-collar status and left the inner city for the suburbs. After 1960, the number of priests and nuns fell rapidly and new vocations were few. The Catholic population was sustained by a large influx from Mexico and other Latin American nations. As the Catholic colleges and universities matured, questions were raised about their adherence to orthodox Catholic theology. After 1980, the Catholic bishops became involved in politics, especially on issues relating to abortion and sexuality.

In the 2014 Religious Landscape Survey published by the Pew Research Center, 20.8% of Americans identified themselves as Catholic.[1]

Colonial Era

In general

The history of Roman Catholicism in the United States – prior to 1776 – often focuses on the 13 English-speaking colonies along the Atlantic seaboard, as it was they who declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, to form the United States of America. However, this history – of Roman Catholicism in the United States – also includes the French and Spanish colonies, because they later became the greater part of the contiguous United States.

Most of the Catholic population in the United States during the colonial period came from England, Germany, and France, with approximately 10,000 Irish Catholics immigrating by 1775,[2] and they all overwhelmingly settled in Maryland and Pennsylvania.[3] In 1700, the estimated population of Maryland was 29,600,[4] about one-tenth of which was Catholic (or approximately 3,000).[5]By 1756, the number of Catholics in Maryland had increased to approximately 7,000,[6] which increased further to 20,000 by 1765.[5] In Pennsylvania, there were approximately 3,000 Catholics in 1756 and 6,000 by 1765.[6][5] By the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, there were approximately 24,000 to 25,000 Catholics in the United States out of a total population of approximately 3 million.[2][5][4]

The current dioceses of the United States are derived from a number of colonial-era dioceses. The following traces the succession of dioceses up to the first diocese that was completely contained in United States territory.

- Spanish dioceses gave rise to many successors in the United States:

- The Spanish parts of the mainland United States were originally part of the Diocese of Mexico established in 1530, and later the Diocese of Durango when it split in 1620.

- California became part of the Diocese of Sonora in 1779. The Diocese of Both Californias, based in San Diego, was established in 1840. After the Mexican–American War, the Mexican potion was split off in 1849, with the United States portion becoming the Diocese of Monterey.

- New Mexico remained part of the Diocese of Durango until after it was annexed by the United States, with the Diocese of Santa Fe established in 1850.

- Texas was organized into a prefecture apostolic in 1839, which became the Diocese of Galveston in 1847.

- Although the French parts of the current United States were originally part of the Diocese of Quebec, after the French and Indian War this was transferred to the Diocese of Santiago de Cuba and later the Diocese of San Cristóbal de la Habana when it was created in 1787. In 1793, the Diocese of Louisiana and the Floridas was created, which was later renamed the Diocese of New Orleans.

- Puerto Rico was originally under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Seville in Spain. The Diocese of San Juan de Puerto Rico was established in 1511.

- Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands were originally part of the Diocese of Cebu in the Philippines. They were split into the Apostolic Prefecture of Mariana Islands in 1902, which became the Diocese of Agaña in 1965.

- The Spanish parts of the mainland United States were originally part of the Diocese of Mexico established in 1530, and later the Diocese of Durango when it split in 1620.

- The English parts were originally under the jurisdiction of the Apostolic Vicariate of the London District. After the American Revolution, the Apostolic Prefecture of the United States was established in 1784, which became the Diocese of Baltimore in 1789.

- The Vicariate Apostolic of the Oregon Territory was established in 1843.

- In 1846, the United States part of Oregon Territory became the Diocese of Oregon City.

- The remainder became the Canadian Diocese of Vancouver Island, from which the Prefecture Apostolic of Alaska was created in 1894. Part of it became the Diocese of Juneau in 1951, with the rest becoming the Diocese of Fairbanks in 1962.

- The Apostolic Vicariate of Eastern Oceania was established in 1833.

- Part of this was split into the Vicariate Apostolic of the Sandwich Islands in 1843, which became the Diocese of Honolulu in 1941.

- Another part was split into the Apostolic Vicariate of Central Oceania in 1842. This became the Diocese of Apia, which included both Samoa and American Samoa, in 1966. In 1982, the American Samoa part was split into the Diocese of Samoa–Pago Pago.

Spanish Missions

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States before the Protestant Reformation with the Spanish explorers and settlers in present-day Florida (1513), South Carolina (1566), Georgia (1568–1684), and the southwest. The first Catholic Mass held in the current United States was in 1526 by Dominican friars Fr. Antonio de Montesinos and Fr. Anthony de Cervantes, who ministered to the San Miguel de Gualdape colonists for the 3 months the colony existed.[8]

The influence of the Alta California missions (1769 and onwards) forms a lasting memorial to part of this heritage. Until the 19th century, the Franciscansand other religious orders had to operate their missions under the Spanish and Portuguese governments and military.[9] Junípero Serra founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions.[10] These missions brought grain, cattle and a new way of living to the Indian tribes of California. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization and founding of San Diego at Mission San Diego de Alcala (1760), Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo at Carmel-by-the-Sea, California in (1770), Mission San Francisco de Asis(Mission Dolores) at San Francisco (1776), Mission San Luis Obispo at San Luis Obispo (1772), Mission Santa Clara de Asis at Santa Clara (1777), Mission Senora Reina de los Angeles Asistencia in Los Angeles (1784), Mission Santa Barbara at Santa Barbara (1786), Mission San Juan Bautista in San Juan Bautista (1797), among numerous others.

French territories

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of missions such as Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan (1668), St. Ignace on the Straits of Mackinac, Michigan (1671) and Holy Family at Cahokia, Illinois (1699) and then colonies and forts in Detroit (1701), St. Louis, Mobile (1702), Kaskaskia, Il (1703), Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans(1718). In the late 17th century, French expeditions, which included sovereign, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. Small settlements were founded along the banks of the Mississippi and its major tributaries, from Louisiana to as far north as the region called the Illinois Country.[11]

The French possessions were under the authority of the diocese of Quebec, under an archbishop, chosen and funded by the king. The religious fervor of the population was very weak; Catholics ignored the tithe, a 10% tax to support the clergy. By 1720, the Ursulines were operating a hospital in New Orleans. The Church did send Companions of the Seminary of Quebec and Jesuits as missionaries, to convert Native Americans. These missionaries introduced the Natives to Catholicism in stages.

English colonies

Catholicism was introduced to the English colonies with the founding of the Province of Maryland.[12] Maryland was one of the few regions among the English colonies in North America that had a sizable Catholic population. However, the 1646 defeat of the Royalists in the English Civil War led to stringent laws against Catholic education and the extradition of known Jesuits from the colony, including Andrew White, and the destruction of their school at Calverton Manor.[13] Due to immigration, by 1660 the population of the Province had gradually become predominantly Protestant. During the greater part of the Maryland colonial period, Jesuits continued to conduct Catholic schools clandestinely.

Maryland was a rare example of religious toleration in a fairly intolerant age, particularly amongst other English colonies which frequently exhibited a militant Protestantism. The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity. It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment.

After Virginia established Anglicanism as mandatory in the colony, numerous Puritans migrated from Virginia to Maryland. The government gave them land for a settlement called Providence (now called Annapolis). In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government and set up a new government that outlawed both Catholicism and Anglicanism. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act.

Origins of anti-Catholicism

American Anti-Catholicism and Nativist Opposition to Catholic immigrants had their origins in the Reformation. Because the Reformation, from the Protestant perspective, was based on an effort by Protestants to correct what they perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Catholic interpretation of the Bible, the Catholic hierarchy and the Papacy. "To be English was to be anti-Catholic," writes Robert Curran.[14] These positions were brought to the eastern seaboard of the New World by British colonists, predominantly Protestant, who opposed not only the Roman Catholic Church in Europe and in French and Spanish-speaking colonies of the New World, but also the policies of the Church of England in their own homeland, which they believed perpetuated Catholic doctrine and practices, and, for that reason, deemed it to be insufficiently Reformed.

Because many of the British colonists were Dissenters, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, and thus were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia."[15] Michael Breidenbach has argued that "a central reason, if not the central reason, why Protestants believed Catholicism was the greatest single threat to civil society and therefore why its adherents could not be tolerated...was the pope’s claim (and Catholics’ apparent acceptance of it) that he held temporal power over all civil rulers, including the right to depose a secular authority."[16] Breidenbach argues that American Catholics did not in fact hold this view, but opponents largely ignored that. Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of Catholics in general could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Before the Revolution, the Southern Colonies and three of the New England Colonies had established churches, either Congregational (Massachusetts Bay, Connecticut, and New Hampshire) or Anglican (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia).[17] This only meant that local tax money was spent for the local church, which sometimes (as in Virginia) handled poor relief and roads. Churches that were not established were tolerated and governed themselves; they functioned with private funds.[18] The Middle Colonies (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware) and the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations had no established churches.[17]

American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, 35,000 Catholics formed 1.2% of the 2.5 million white population of the thirteen seaboard colonies.[19] One of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll (1737-1832), owner of sixty thousand acres of land, was a Catholic and was one of the richest men in the colonies. Catholicism was integral to his career. He was dedicated to American Republicanism, but feared extreme democracy.[20][21]

Before independence in 1776 the Catholics in Britain's thirteen colonies in America were under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of the London District, in England.

A petition was sent by the Maryland clergy to the Holy See, on November 6, 1783, for permission for the missionaries in the United States to nominate a superior who would have some of the powers of a bishop. In response to that, Father John Carroll – having been selected by his brother priests – was confirmed by Pope Pius VI, on June 6, 1784, as Superior of the Missions in the United States, with power to give the sacrament of confirmation. This act established a hierarchy in the United States.

The Holy See then established the Apostolic Prefecture of the United States on November 26, 1784. Because Maryland was one of the few regions of the new country that had a large Catholic population, the apostolic prefecture was elevated to become the Diocese of Baltimore[22] – the first diocese in the United States – on November 6, 1789.[23]

Thus, Father John Carroll, a former Jesuit, became the first American-born head of the Catholic Church in America, although the papal suppression of the Jesuit order was still in effect. Carroll orchestrated the founding and early development of Georgetown University which began instruction on November 22, 1791.[24] On March 29, 1800 Carroll ordained William Matthews as the first British-America-born Catholic priest.[25]

In 1788, after the Revolution, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil."[26] In one state, North Carolina, the Protestant test oath would not be changed until 1868.

19th century

The Catholic population of the United States, which had been 35,000 in 1790, increased to 195,000 in 1820 and then ballooned to about 1.6 million in 1850, by which time, Catholics had become the country's largest denomination. Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled primarily through immigration and high birth rates. By the end of the century, there were 12 million Catholics in the United States.

During the mid 19th century, a wave of "old" immigrants from Europe arrived from Ireland and Germany, as well as England and the Netherlands. From the 1880s to 1914 a "new" wave arrived from Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe. Substantial numbers of Catholics also came from French Canada during the mid-19th century and settled in New England. After 1911 large numbers of Mexicans arrived.

Many Catholics stopped practicing their religion or became Protestants. However, there were about 700,000 converts to Catholicism from 1813 to 1893.[27]

Archdiocese of Baltimore

Because Maryland was one of the few regions of the colonial United States that was predominantly Catholic, the first diocese in the United States was established in Baltimore. Thus, the Diocese of Baltimore achieved a pre-eminence over all future dioceses in the U.S. It was established as a diocese on November 6, 1789, and was elevated to the status of an archdiocese on April 8, 1808.

In 1858, the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide), with the approval of Pius IX, conferred "Prerogative of Place" on the Archdiocese of Baltimore. This decree gave the archbishop of Baltimore precedence over all the other archbishops of the United States (but not cardinals) in councils, gatherings, and meetings of whatever kind of the hierarchy (in conciliis, coetibus et comitiis quibuscumque) regardless of the seniority of other archbishops in promotion or ordination.[28]

The dominance of Irish Americans

Beginning in the 1840s, Irish American Catholics comprised most of the bishops and controlled most of the Catholic colleges and seminaries in the United States. In 1875, John McCloskey of New York became the first American cardinal.

Parochial schools[edit]

The development of the American Catholic parochial school system can be divided into three phases. During the first (1750–1870), parochial schools appeared as ad hoc efforts by parishes, and most Catholic children attended public schools. During the second period (1870–1910), the Catholic hierarchy made a basic commitment to a separate Catholic school system. These parochial schools, like the big-city parishes around them, tended to be ethnically homogeneous; a German child would not be sent to an Irish school, nor vice versa, nor a Lithuanian pupil to either. Instruction in the language of the old country was common. In the third period (1910–1945), Catholic education was modernized and modeled after the public school systems, and ethnicity was deemphasized in many areas. In cities with large Catholic populations (such as Chicago and Boston) there was a flow of teachers, administrators, and students from one system to the other.[29]

Catholic schools began as a program to shelter Catholic students from Protestant teachers (and schoolmates) in the new system of public schools that emerged in the 1840s.

In 1875, Republican President Ulysses S. Grant called for a Constitutional amendment that would prohibit the use of public funds for "sectarian" schools. Grant feared a future with "patriotism and intelligence on one side and superstition, ambition and greed on the other" which he identified with the Catholic Church. Grant called for public schools that would be "unmixed with atheistic, pagan or sectarian teaching." No such federal constitutional amendment ever passed, but most states did pass so-called "Blaine Amendments" that prohibited the use of public funds to fund parochial schools and are still in effect today.

Slavery debate[edit]

Two slaveholding states, Maryland and Louisiana, had large contingents of Catholic residents. Archbishop of Baltimore, John Carroll, had two black servants – one free and one a slave. The Society of Jesus owned a large number of slaves who worked on the community's farms. Realizing that their properties were more profitable if rented out to tenant farmers rather that worked by slaves, the Jesuits began selling off their slaves in 1837.

In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI issued a Bull, titled In Supremo. Its main focus was against slave trading, but it also clearly condemned racial slavery:

- We, by apostolic authority, warn and strongly exhort in the Lord faithful Christians of every condition that no one in the future dare bother unjustly, despoil of their possessions, or reduce to slavery Indians, Blacks or other such peoples.

However, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, to support slaveholding interests. Some American bishops misinterpreted In Supremo as condemning only the slave trade and not slavery itself. Bishop John England of Charleston actually wrote several letters to the Secretary of State under President Van Buren explaining that the Pope, in In Supremo, did not condemn slavery but only the slave trade.[30]

One outspoken critic of slavery was Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of Cincinnati, Ohio. In an 1863 Catholic Telegraph editorial Purcell wrote:

- "When the slave power predominates, religion is nominal. There is no life in it. It is the hard-working laboring man who builds the church, the school house, the orphan asylum, not the slaveholder, as a general rule. Religion flourishes in a slave state only in proportion to its intimacy with a free state, or as it is adjacent to it."

During the war, American bishops continued to allow slave-owners to take communion. During the Civil War, some like former priest Charles Chiniquy claimed that Pope Pius IX was behind the Confederate cause, that the American Civil War was a plot against the United States of America by the Vatican. The Catholic Church, having by its very nature a universal view, urged a unity of spirit. Catholics in the North rallied to enlist. Nearly 150,000 Irish Catholics fought for the Union, many in the famed Irish Brigade, as well as approximately 40,000 German-Catholics, and 5,000 Polish-Catholic immigrants. Catholics became prominent in the officer corps, including over fifty generals and a half-dozen admirals. Along with the soldiers that fought in the ranks were hundreds of priests who ministered to the troops and Catholic religious sisters who assisted as nurses and sanitary workers.

After the war, in October 1866, President Andrew Johnson and Washington's mayor attended the closing session of a plenary council in Baltimore, giving tribute to the role Catholics played in the war and to the growing Catholic presence in America.

African-American Catholics

Because the South was over 90% Protestant, most African-Americans who adopted Christianity became Protestant; some became Catholics in the Gulf South, particularly Louisiana. The French Code Noir which regulated the role of slaves in colonial society guaranteed the rights of slaves to baptism, religious education, communion, and marriage. The parish church in New Orleans was unsegregated. Predominantly black religious orders emerged, including the Sisters of the Holy Family in 1842. The Church of Saint Augustine in the Tremé district is among a number of historically black parishes. Xavier University, America's only historically-black Catholic institute of higher learning, was founded in New Orleans by Saint Katherine Drexel in 1915.[31]

Maryland Catholics owned slaves starting in the colonial era; in 1785, about 3000 of the 16,000 Catholics were black. Some owners and slaves moved west to Kentucky.[32] In 1835, Bishop John England, established free schools for black children in Charleston, South Carolina. White mobs forced it to close. African-American Catholics operated largely as segregated enclaves. They also founded separate religious institutes for black nuns and priests since diocesan seminaries would not accept them. For example, they formed two separate communities of black nuns: the Oblate Sisters of Providence in 1829 and the Holy Family Sisters in 1842.

James Augustine Healy was the first African American to become a priest. , became the second bishop of the Diocese of Portland, Maine in 1875. His brother, Patrick Francis Healy, joined the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) at the novitiate in Frederick, Maryland in 1850. Because of the rising threat of Civil War and the Jesuit custom of pursuing further studies in Europe, he was sent to Belgium in 1858. He earned a doctorate at the university of Leuven, becoming the first American of African descent to earn a doctorate; and he was ordained a priest in Liege, France in 1864. Immediately following the Civil War he was ordered to return to the U.S. and began teaching at Georgetown University, which he became president of in 1874.[33]

In 1866, Archbishop Martin J. Spalding of Baltimore convened the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore, partially in response to the growing need for religious care for former slaves. Attending bishops remained divided over the issue of separate parishes for African-American Catholics.

In 1889, Daniel Rudd, a former slave and Ohio journalist, organized the National Black Catholic Congress, the first national organization for African-American Catholic lay men. The Congress met in Washington, D.C. and discussed issues such as education, job training, and "the need for family virtues."[34]

In 2001, Bishop Wilton Gregory was appointed president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the first African American ever to head an episcopal conference.

Plenary Councils of Baltimore

Catholic bishops met in three of Plenary Councils in Baltimore in 1852, 1866 and 1884, establishing national policies for all diocese.[35] One result of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884 was the development of the Baltimore Catechism which became the standard text for Catholic education in the United States and remained so until the 1960s when Catholic churches and schools began moving away from catechism-based education.[36]

Another result of this council was the establishment of The Catholic University of America, the national Catholic university in the United States.

Labor union movement[edit]

Irish Catholics took a prominent role in shaping America's labor movement. Most Catholics were unskilled or semi-skilled urban workers, and the Irish used their strong sense of solidarity to form a base in unions and in local Democratic politics. By 1910 a third of the leadership of the labor movement was Irish Catholic, and German Catholics were actively involved as well.[37]

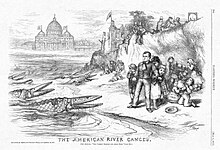

Anti-Catholicism[edit]

Some anti-immigrant and Nativism movements, like the Know Nothings have also been anti-Catholic. Anti-Catholicism was led by Protestant ministers who labeled Catholics as un-American "Papists", incapable of free thought without the approval of the Pope, and thus incapable of full republican citizenship. This attitude faded after Catholics proved their citizenship by service in the American Civil War, but occasionally emerged in political contests, especially the presidential elections of 1928 and 1960, when Catholics were nominated by the Democratic Party. Democrats won 65–80% of the Catholic vote in most elections down to 1964, but since then have split about 50-50. Typically, Catholics have taken conservative positions on anti-communism and sexual behavior, and liberal positions on the welfare state.[38]

Americanist controversy

Americanism was considered a heresy by the Vatican that consisted of too much theological liberalism and too ready acceptance of the American policy of separation of church and state. Rome feared that such a heresy was held by Irish Catholic leaders in the United States, such as Isaac Hecker, and bishops John Keane, John Ireland, and John Lancaster Spalding, as well as the magazines Catholic World and Ave Marie. Allegations came from German American bishops angry with growing Irish domination of the Church.

The Vatican grew alarmed in the 1890s, and the Pope issued an encyclical denouncing Americanism in theory. In "Longinqua oceani" (1895; “Wide Expanse of the Ocean”), Pope Leo XIII warned the American hierarchy not to export their unique system of separation of church and state. In 1898 he lamented an America where church and state are "dissevered and divorced," and wrote of his preference for a closer relationship between the Catholic Church and the State. Finally, in his pastoral letter Testem benevolentiae (1899; “Witness to Our Benevolence”) to Cardinal James Gibbons, Pope Leo XIII condemned other forms of Americanism. In response, Gibbons denied that American Catholics held any of the condemned views.

Leo's pronouncements effectively ended the Americanist movement and curtailed the activities of American progressive Catholics. The Irish Catholics increasingly demonstrated their total loyalty to the Pope, and traces of liberal thought in the Catholic colleges were suppressed. At bottom it was a cultural conflict, as the conservative Europeans were alarmed mostly by the heavy attacks on the Catholic church in Germany, France and other countries, and did not appreciate the active individualism self-confidence and optimism of the American church. In reality Irish Catholic laymen were deeply involved in American politics, but the bishops and priests kept their distance.[39][40]