Textbook Reading: Northouse Chapter 4

Behavioral Approach

Description

The style approach emphasizes the behavior of the leader. This distinguishes it from the trait approach (Chapter 2), which emphasizes the personality characteristics of the leader, and the skills approach (Chapter 3), which emphasizes the leader’s capabilities. The behavioral approach focuses exclusively on what leaders do and how they act. In shifting the study of leadership to leader behaviors, the behavioral approach expanded the research of leadership to include the actions of leaders toward followers in various contexts.

Researchers studying the behavioral approach determined that leadership is composed of two general kinds of behaviors: task behaviors and relationship behaviors. Task behaviors facilitate goal accomplishment: They help group members to achieve their objectives. Relationship behaviors help followers feel comfortable with themselves, with each other, and with the situation in which they find themselves. The central purpose of the behavioral approach is to explain how leaders combine these two kinds of behaviors to influence followers in their efforts to reach a goal.

Many studies have been conducted to investigate the behavioral approach. Some of the first studies to be done were conducted at The Ohio State University in the late 1940s, based on the findings of Stogdill’s (1948) work, which pointed to the importance of considering more than leaders’ traits in leadership research. At about the same time, another group of researchers at the University of Michigan was conducting a series of studies that explored how leadership functioned in small groups. A third line of research was begun by Blake and Mouton in the early 1960s; it explored how managers used task and relationship behaviors in the organizational setting.

Although many research studies could be categorized under the heading of the behavioral approach, the Ohio State studies, the Michigan studies, and the studies by Blake and Mouton (1964, 1978, 1985) are strongly representative of the ideas in this approach. By looking closely at each of these groups of studies, we can draw a clearer picture of the underpinnings and implications of the behavioral approach. The Ohio State Studies A group of researchers at Ohio State believed that the results of studying leadership as a personality trait seemed fruitless and decided to analyze how individuals acted when they were leading a group or an organization. This analysis was conducted by having followers complete questionnaires about their leaders. On the questionnaires, followers had to identify the number of times their leaders engaged in certain types of behaviors.The original questionnaire used in these studies was constructed from a list of more than 1,800 items describing different aspects of leader behavior. From this long list of items, a questionnaire composed of 150 questions was formulated; it was called the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ ; Hemphill & Coons, 1957). The LBDQ was given to hundreds of people in educational, military, and industrial settings, and the results showed that certain clusters of behaviors were typical of leaders. Six years later, Stogdill (1963) published a shortened version of the LBDQ . The new form, which was called the LBDQ-XII, became the most widely used instrument in leadership research. A questionnaire similar to the LBDQ , which you can use to assess your own leadership behavior, appears later in this chapter.

Researchers found that followers’ responses on the questionnaire clustered around two general types of leader behaviors: initiating structure and consideration (Stogdill, 1974). Initiating structure behaviors are essentially task behaviors, including such acts as organizing work, giving structure to the work context, defining role responsibilities, and scheduling work activities. Consideration behaviors are essentially relationship behaviors and include building camaraderie, respect, trust, and liking between leaders and followers.

The two types of behaviors identified by the LBDQ-XII represent the core of the behavioral approach and are central to what leaders do: Leaders provide structure for followers, and they nurture them. The Ohio State studies viewed these two behaviors as distinct and independent. They were thought of not as two points along a single continuum, but as two different continua. For example, a leader can be high in initiating structure and high or low in task behavior. Similarly, a leader can be low in setting structure and low or high in consideration behavior. The degree to which a leader exhibits one behavior is not related to the degree to which she or he exhibits the other behavior.

Many studies have been done to determine which leadership behavior is most effective in a particular situation. In some contexts, high consideration has been found to be most effective, but in other situations, high initiating structure is most effective. Some research has shown that being high in both behaviors is the best form of leadership. Determining how a leader optimally mixes task and relationship behaviors has been the central task for researchers from the behavioral approach. The path–goal approach, which is discussed in Chapter 6, exemplifies a leadership theory that attempts to explain how leaders should integrate consideration and structure into their behaviors.

The University of Michigan Studies

Whereas researchers at Ohio State were developing the LBDQ , researchers at the University of Michigan were also exploring leadership behavior, giving special attention to the impact of leaders’ behaviors on the performance of small groups (Cartwright & Zander, 1960; Katz & Kahn, 1951; Likert, 1961, 1967).

The program of research at Michigan identified two types of leadership behaviors: employee orientation and production orientation. Employee orientation is the behavior of leaders who approach subordinates with a strong human relations emphasis. They take an interest in workers as human beings, value their individuality, and give special attention to their personal needs (Bowers & Seashore, 1966). Employee orientation is very similar to the cluster of behaviors identified as consideration in the Ohio State studies.

Production orientation consists of leadership behaviors that stress the technical and production aspects of a job. From this orientation, workers are viewed as a means for getting work accomplished (Bowers & Seashore, 1966). Production orientation parallels the initiating structure cluster found in the Ohio State studies.

Unlike the Ohio State researchers, the Michigan researchers, in their initial studies, conceptualized employee and production orientations as opposite ends of a single continuum. This suggested that leaders who were oriented toward production were less oriented toward employees, and those who were employee oriented were less production oriented. As more studies were completed, however, the researchers reconceptualized the two constructs, as in the Ohio State studies, as two independent leadership orientations (Kahn, 1956). When the two behaviors are treated as independent orientations, leaders are seen as being able to be oriented toward both production and employees at the same time.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a multitude of studies were conducted by researchers from both Ohio State and the University of Michigan to determine how leaders could best combine their task and relationship behaviors to maximize the impact of these behaviors on the satisfaction and performance of followers. In essence, the researchers were looking for a universal theory of leadership that would explain leadership effectiveness in every situation. The results that emerged from this large body of literature were contradictory and unclear (Yukl, 1994). Although some of the findings pointed to the value of a leader being both highly task-oriented and highly relationship-oriented in all situations (Misumi, 1985), the preponderance of research in this area was inconclusive.

Blake and Mouton’s Managerial (Leadership) Grid

Perhaps the best-known model of managerial behavior is the Managerial Gridâ, which first appeared in the early 1960s and has been refined and revised several times (Blake & McCanse, 1991; Blake & Mouton, 1964, 1978, 1985). It is a model that has been used extensively in organizational training and development. The Managerial Grid, which has been renamed the Leadership Gridâ, was designed to explain how leaders help organizations to reach their purposes through two factors: concern for production and concern for people. Although these factors are described as leadership orientations in the model, they closely parallel the task and relationship leadership behaviors we have been discussing throughout this chapter.

Concern for production refers to how a leader is concerned with achieving organizational tasks. It involves a wide range of activities, including attention to policy decisions, new product development, process issues, workload, and sales volume, to name a few. Not limited to an organization’s manufactured product or service, concern for production can refer to whatever the organization is seeking to accomplish (Blake & Mouton, 1964).

Concern for people refers to how a leader attends to the people in the organization who are trying to achieve its goals. This concern includes

building organizational commitment and trust, promoting the personal worth of followers, providing good working conditions, maintaining a fair salary structure, and promoting good social relations (Blake & Mouton, 1964).

The Leadership (Managerial) Grid joins concern for production and concern for people in a model that has two intersecting axes (Figure 4.1). The horizontal axis represents the leader’s concern for results, and the vertical axis represents the leader’s concern for people. Each of the axes is drawn as a 9-point scale on which a score of 1 represents minimum concern and 9 represents maximum concern. By plotting scores from each of the axes, various leadership styles can be illustrated. The Leadership Grid portrays five major leadership styles: authority–compliance (9,1), country-club management (1,9), impoverished management (1,1), middle-of-the-road

management (5,5), and team management (9,9).

Authority–compliance (9,1)

The 9,1 style of leadership places heavy emphasis on task and job requirements, and less emphasis on people, except to the extent that people are tools for getting the job done. Communicating with subordinates is not emphasized except for the purpose of giving instructions about the task. This style is result driven, and people are regarded as tools to that end. The 9,1 leader is often seen as controlling, demanding, hard driving, and overpowering.

country-club Management (1,9)

The 1,9 style represents a low concern for task accomplishment coupled with a high concern for interpersonal relationships. Deemphasizing production, 1,9 leaders stress the attitudes and feelings of people, making sure the personal and social needs of followers are met. They try to create a positive climate by being agreeable, eager to help, comforting, and uncontroversial.

impoverished Management (1,1)

The 1,1 style is representative of a leader who is unconcerned with both the task and interpersonal relationships. This type of leader goes through the motions of being a leader but acts uninvolved and withdrawn. The 1,1 leader

often has little contact with followers and could be described as indifferent, noncommittal, resigned, and apathetic.

Middle-of-the-road Management (5,5)

The 5,5 style describes leaders who are compromisers, who have an intermediate concern for the task and an intermediate concern for the people who do the task. They find a balance between taking people into account and still emphasizing the work requirements. Their compromising style

gives up some of the push for production and some of the attention to employee needs. To arrive at an equilibrium, the 5,5 leader avoids conflict and emphasizes moderate levels of production and interpersonal relationships. This type of leader often is described as one who is expedient, prefers the middle ground, soft-pedals disagreement, and swallows convictions in the interest of “progress.”

team Management (9,9)

The 9,9 style places a strong emphasis on both tasks and interpersonal relationships. It promotes a high degree of participation and teamwork in the organization and satisfies a basic need in employees to be involved and committed to their work. The following are some of the phrases that could be used to describe the 9,9 leader: stimulates participation, acts determined, gets issues into the open, makes priorities clear, follows through, behaves open-mindedly, and enjoys working.

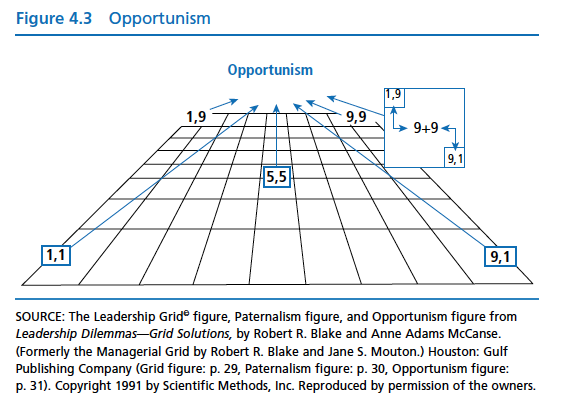

In addition to the five major styles described in the Leadership Grid, Blake and his colleagues have identified two other behaviors that incorporate multiple aspects of the grid.

Paternalism/maternalism refers to a leader who uses both 1,9 and 9,1 styles but does not integrate the two (Figure 4.2). This is the “benevolent dictator” who acts graciously but does so for the purpose of goal accomplishment. In essence, the paternalistic/maternalistic style treats people as if they were dissociated from the task. Paternalistic/maternalistic leaders are often described as “fatherly” or “motherly” toward their followers; regard the organization as a “family”; make most of the key decisions; and reward loyalty and obedience while punishing noncompliance.

Opportunism refers to a leader who uses any combination of the basic five styles for the purpose of personal advancement (Figure 4.3). An opportunistic leader will adapt and shift his or her leadership behavior to gain personal advantage, putting self-interest ahead of other priorities. Both the performance and the effort of the leader are to realize personal gain. Some phrases used to describe this leadership behavior include ruthless, cunning,

and self-motivated, while some could argue that these types of leaders are

adaptable and strategic.

Blake and Mouton (1985) indicated that people usually have a dominant grid style (which they use in most situations) and a backup style. The backup style is what the leader reverts to when under pressure, when the usual way of accomplishing things does not work.

In summary, the Leadership Grid is an example of a practical model of leadership that is based on the two major leadership behaviors: task and relationship. It closely parallels the ideas and findings that emerged in the Ohio State and University of Michigan studies. It is used in consulting for organizational development throughout the world.

How Does the Behavioral Approach work?

Unlike many of the other approaches discussed in the book, the behavioral approach is not a refined theory that provides a neatly organized set of prescriptions for effective leadership behavior. Rather, the behavioral approach provides a framework for assessing leadership in a broad way, as behavior with a task and relationship dimension. The behavioral approach

works not by telling leaders how to behave, but by describing the major components of their behavior.

The behavioral approach reminds leaders that their actions toward others occur on a task level and a relationship level. In some situations, leaders need to be more task oriented, whereas in others they need to be more relationship oriented. Similarly, some followers need leaders who provide a lot of direction, whereas others need leaders who can show them a great deal of nurturance and support. The behavioral approach gives the leader a way to look at his or her own behavior by subdividing it into two dimensions.

An example may help explain how the behavioral approach works. Imagine two college classrooms on the first day of class and two professors with entirely different styles. Professor Smith comes to class, introduces herself, takes attendance, goes over the syllabus, explains the first assignment, and dismisses the class. Professor Jones comes to class and, after introducing herself and handing out the syllabus, tries to help the students to get to know one another by having each of the students describe a little about themselves, their majors, and their favorite nonacademic activities. The leadership behaviors of professors Smith and Jones are quite different. The preponderance of what Professor Smith does could be labeled task behavior, and the majority of what Professor Jones does could be labeled relationship

behavior. The behavioral approach provides a way to inform the professors about the differences in their behaviors. Depending on the response of the students to their leadership behaviors, the professors may want to change their behavior to improve their teaching on the first day of class.

Overall, the behavioral approach offers a means of assessing in a general way the behaviors of leaders. It reminds leaders that their impact on others occurs through the tasks they perform as well as in the relationships they create.

Strengths

The behavioral approach makes several positive contributions to our understanding of the leadership process. First, the behavioral approach marked a major shift in the general focus of leadership research. Before the inception of this approach, researchers treated leadership exclusively as a trait (see Chapter 2). The behavioral approach broadened the scope of leadership research to include the behaviors of leaders and what they do in various situations. No longer was the focus of leadership on the personal characteristics of leaders: It was expanded to include what leaders did and how they acted.

Second, a wide range of studies on leadership behavior validates and gives credibility to the basic tenets of the approach. First formulated and reported by researchers from The Ohio State University and the University of Michigan, and subsequently reported in the works of Blake and Mouton (1964, 1978, 1985) and Blake and McCanse (1991), the behavioral approach is substantiated by a multitude of research studies that offer a viable approach to understanding the leadership process.

Third, on a conceptual level, researchers of the behavioral approach have ascertained that a leader’s style consists primarily of two major types of behaviors: task and relationship. The significance of this idea is not to be understated. Whenever leadership occurs, the leader is acting out both task and relationship behaviors; the key to being an effective leader often rests on how the leader balances these two behaviors. Together they form the core of the leadership process.

Fourth, the behavioral approach is heuristic. It provides us with a broad conceptual map that is worthwhile to use in our attempts to understand the complexities of leadership. Leaders can learn a lot about themselves and how they come across to others by trying to see their behaviors in light of the task and relationship dimensions. Based on the behavioral approach, leaders can

assess their actions and determine how they may want to change to improve their leadership behaviors.

Criticisms

Along with its strengths, the behavioral approach also has several weaknesses. First, the research on the behavioral approach has not adequately shown how leaders’ behaviors are associated with performance outcomes (Bryman, 1992; Yukl, 1994). Researchers have not been able to establish a consistent link between task and relationship behaviors and outcomes such as morale, job satisfaction, and productivity. According to Yukl (1994, p. 75), the “results from this massive research effort have been mostly contradictory and inconclusive.” He further pointed out that the only strong finding about leadership behaviors is that leaders who are considerate have followers who are more satisfied.

Another criticism is that this approach has failed to find a universal style of leadership that could be effective in almost every situation. The overarching goal for researchers studying the behavioral approach appeared to be the identification of a universal set of leadership behaviors that would consistently result in effective outcomes. Because of inconsistencies in the research findings, this goal was never reached. Similar to the trait approach, which was unable to identify the definitive personal characteristics of leaders, the behavioral approach has been unable to identify the universal behaviors that are associated with effective leadership.

A final criticism of the behavioral approach is that it implies that the most effective leadership style is the high–high style (i.e., high task and high relationship). Although some researchers (e.g., Blake & McCanse, 1991; Misumi, 1985) suggested that high–high managers are most effective, that may not be the case in all situations. In fact, the full range of research findings provides only limited support for a universal high–high style (Yukl, 1994). Certain situations may require different leadership styles; some may be complex and require high- task behavior, and others may be simple and require supportive behavior. At this point in the development of research on the behavioral approach, it remains unclear whether the high–high style is the best style of leadership.

Application

The behavioral approach can be applied easily in ongoing leadership settings. At all levels in all types of organizations, managers are continually engaged in task and relationship behaviors. By assessing their own behaviors, managers can determine how they are coming across to others and how they could change their behaviors to be more effective. In essence, the behavioral approach provides a mirror for managers that is helpful in answering the frequently asked question, “How am I doing as a leader?”

Many leadership training and development programs throughout the country are structured along the lines of the behavioral approach. Almost all are designed similarly and include giving managers questionnaires that assess in some way their task and relationship behaviors toward followers. Participants use these assessments to improve their overall leadership behavior.

An example of a training and development program that deals exclusively with leader behaviors is Blake and Mouton’s Leadership Grid (formerly Managerial Grid) seminar. Grid seminars are about increasing productivity, improving morale, and gaining employee commitment. They are offered by Grid International, an international organization development company (www.gridinternational.com). At grid seminars, self-assessments, small- group experiences, and candid critiques allow managers to learn how to define effective leadership, how to manage for optimal results, and how to identify and change ineffective leadership behaviors. The conceptual framework around which the grid seminars are structured is the behavioral approach to leadership.

In short, the behavioral approach applies to nearly everything a leader does. It is an approach that is used as a model by many training and development companies to teach managers how to improve their effectiveness and organizational productivity.

engaged in task and relationship behaviors. By assessing their own behaviors, managers can determine how they are coming across to others and how they could change their behaviors to be more effective. In essence, the behavioral approach provides a mirror for managers that is helpful in answering the frequently asked question, “How am I doing as a leader?” Many leadership training and development programs throughout the country are structured along the lines of the behavioral approach. Almost all are designed similarly and include giving managers questionnaires that assess in some way their task and relationship behaviors toward followers. Participants use these assessments to improve their overall leadership behavior. An example of a training and development program that deals exclusively with leader behaviors is Blake and Mouton’s Leadership Grid (formerly Managerial Grid) seminar. Grid seminars are about increasing productivity, improving morale, and gaining employee commitment. They are offered by Grid International, an international organization development company (www.gridinternational.com). At grid seminars, self-assessments, small- group experiences, and candid critiques allow managers to learn how to define effective leadership, how to manage for optimal results, and how to identify and change ineffective leadership behaviors. The conceptual framework around which the grid seminars are structured is the behavioral approach to leadership. In short, the behavioral approach applies to nearly everything a leader does. It is an approach that is used as a model by many training and development companies to teach managers how to improve their effectiveness and organizational productivity.In this section, you will find three case studies (Cases 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3) that describe the leadership behaviors of three different managers, each of whom is working in a different organizational setting. The first case is about a maintenance director in a large hospital, the second deals with a supervisor in a small sporting goods store, and the third is concerned with the director of marketing and communications at a college. At the end of each case are questions that will help you to analyze the case from the perspective of the style approach.

Case 4.1

A Drill Sergeant at First Mark Young is the head of the painting department in a large hospital; 20 union employees report to him. Before coming on board at the hospital, he had worked as an independent contractor. At the hospital, he took a position that was newly created because the hospital believed change was needed in how painting services were provided.

Upon beginning his job, Mark did a 4-month analysis of the direct and indirect costs of painting services. His findings supported the perceptions of his administrators that painting services were inefficient and costly. As a result, Mark completely reorganized the department, designed a new scheduling procedure, and redefined the expected standards of performance.

Mark says that when he started out in his new job he was “all task,” like a drill sergeant who didn’t seek any input from his subordinates. From Mark’s point of view, the hospital environment did not leave much room for errors, so he needed to be strict about getting painters to do a good job within the constraints of the hospital environment.

As time went along, Mark relaxed his style and was less demanding. He delegated some responsibilities to two crew leaders who reported to him, but he always stayed in close touch with each of the employees. On a weekly basis, Mark was known to take small groups of workers to the local sports bar for burgers on the house. He loved to banter with the employees and could take it as well as dish it out.

Mark is very proud of his department. He says he always wanted to be a coach, and that’s how he feels about running his department. He enjoys working with people; in particular, he says he likes to see the glint in their eyes when they realize that they’ve done a good job and they have done it on their own.

Because of Mark’s leadership, the painting department has improved substantially and is now seen by workers in other departments as the most productive department in hospital maintenance. Painting services received a customer rating of 92%, which is the highest of any service in the hospital.

Questions

1. From the behavioral perspective, how would you describe Mark’s leadership?

2. How did his behavior change over time?

3. In general, do you think he is more task-oriented or more relationship-oriented?

4. What score do you think he would get on Blake and Mouton’s grid?

Case 4.2

Eating Lunch Standing UpSusan Parks is the part–owner and manager of Marathon Sports, an athletic equipment store that specializes in running shoes and accessories. The store employs about 10 people, most of whom are college students who work part-time during the week and full-time on weekends. Marathon Sports is the only store of its kind in a college town with a population of 125,000. The annual sales figures for the store have shown 15% growth each year.

Susan has a lot invested in the store, and she works very hard to make sure the store continues to maintain its reputation and pattern of growth. She works 50 hours a week at the store, where she wears many hats, including those of buyer, scheduler, trainer, planner, and salesperson. There is never a moment when Susan is not doing something. Rumor has it that she eats her lunch standing up.

Employees’ reactions to Susan are strong and varied. Some people like her style, and others do not. Those who like her style talk about how organized and efficient the store is when she is in charge. Susan makes the tasks and goals for everyone very clear. She keeps everyone busy; when they go home at night, they feel as if they have accomplished something. They like to work for Susan because she knows what she is doing. Those who do not like her style complain that she is too driven. It seems that her sole purpose for being at the store is to get the job done. She seldom, if ever, takes a break or just hangs out with the staff. These people say Susan is pretty hard to relate to, and as a result it is not much fun working at Marathon Sports.

Susan is beginning to sense that employees have a mixed reaction to her leadership style. This bothers her, but she does not know what to do about it. In addition to her work at the store, Susan struggles hard to be a good spouse and mother of three children.

Questions

1. According to the behavioral approach, how would you describe Susan’s leadership?

2. Why does her leadership behavior create such a pronounced reaction from her subordinates?

3. Do you think she should change her behavior?

4. Would she be effective if she changed?

Case 4.3

We Are Family

Betsy Moore has been hired as the director of marketing and communications for a medium-sized college in the Midwest. With a long history of success as a marketing and public relations professional, she was the unanimous choice of the hiring committee. Betsy is excited to be working for Marianne, the vice president of college advancement, who comes from a similar background to Betsy’s. In a meeting with Marianne, Betsy is told the college needs an aggressive plan to revamp and energize the school’s marketing and communications efforts. Betsy and Marianne seem in perfect sync with the direction they believe is right for the college’s program. Marianne also explains that she has established a departmental culture of teamwork and empowerment and that she is a strong advocate of being a mentor to her subordinates rather than a manager.

Betsy has four direct reports: two writers, Bridget and Suzanne, who are young women in their 20s; and Carol and Francine, graphic designers who are in their 50s. In her first month, Betsy puts together a meeting with her direct reports to develop a new communications plan for the college, presenting the desired goals to the team and asking for their ideas on initiatives and improvements to meet those goals. Bridget and Suzanne provide little in the way of suggested changes, with Bridget asking pointedly, “Why do we need to change anything?”

In her weekly meeting with the vice president, Betsy talks about the resistance to change she encountered from the team. Marianne nods, saying she heard some of the team members’ concerns when she went to lunch with them earlier in the week. When Betsy looks surprised, Marianne gives her a knowing smile. “We are like a family here; we have close relationships outside of work. I go to lunch or the movies with Suzanne and Bridget at least once a week. But don’t worry; I am only a sounding board for them, and encourage them to come to you to resolve their issues. They know you are their boss.”

But they don’t come to Betsy. Soon, Bridget stops coming to work at 8 a.m., showing up at 10 a.m. daily. As a result, she misses the weekly planning meetings. When Betsy approaches her about it, Bridget tells her, “It’s OK with Marianne; she says as long as I am using the time to exercise and improve my health she supports it.”

Betsy meets with Suzanne to implement some changes to Suzanne’s pet project, the internal newsletter. Suzanne gets blustery and tearful, accusing Betsy of insulting her work. Later, Betsy watches Suzanne and Marianne leave the office together for lunch. A few hours later, Mariannecomes into Betsy’s office and tells her, “Go easy on the newsletter changes. Suzanne is an insecure person, and she is feeling criticized and put down by you right now.”

Betsy’s relationship with the other two staff members is better. Neither seems to have the close contact with Marianne that the younger team members have. They seem enthusiastic and supportive of the new direction Betsy wants to take the program in.

As the weeks go by, Marianne begins having regular “Mentor Meetings” with Bridget and Suzanne, going to lunch with both women at least twice a week. After watching the three walk out together one day, Francine asks Betsy if it troubles her. Betsy replies, as calmly as she can, “It is part of Marianne’s mentoring program.”

Francine rolls her eyes and says, “Marianne’s not mentoring anyone; she just wants someone to go to lunch with every day.”

After 4 months on the job, Betsy goes to Marianne and outlines the challenges that the vice president’s close relationships with Bridget and Suzanne have presented to the progress of the marketing and communications program. She asks her directly, “Please stop.”

Marianne gives her the knowing, motherly smile again. “I see a lot of potential in Bridget and Suzanne and want to help foster that,” she explains. “They are still young in their careers, and my relationship with them is important because I can provide the mentoring and guidance to develop their abilities.”

“But it’s creating problems between them and me,” Betsy points out. “I can’t manage them if they can circumvent me every time they disagree with me. We aren’t getting any work done. You and I have to be on the same team.”

Marianne shakes her head. “The problem is that we have very different leadership styles. I like to empower people, and you like to boss them around.”

Questions

1. Marianne and Betsy do indeed have different leadership styles. What style would you ascribe to Betsy? To Marianne?

2. Does Betsy need to change her leadership style to improve the situation with Bridget and Suzanne? Does Marianne need to change her style of leadership?

3. How can Marianne and Betsy work together?

Leadership Instrument

Researchers and practitioners alike have used many different instruments to assess the behaviors of leaders. The two most commonly used measures have been the LBDQ (Stogdill, 1963) and the Leadership Grid (Blake & McCanse, 1991). Both of these measures provide information about the degree to which a leader acts task directed or people directed. The LBDQ was designed primarily for research and has been used extensively since the 1960s. The Leadership Grid was designed primarily for training and development; it continues to be used today for training managers and supervisors in the leadership process.

To assist you in developing a better understanding of how leadership behaviors are measured and what your own behavior might be, a leadership behavior questionnaire is included in this section. This questionnaire is made up of 20 items that assess two orientations: task and relationship. By scoring the Leadership Behavior Questionnaire, you can obtain a general profile of your leadership behavior.

leadership Behavior Questionnaire

Instructions: read each item carefully and think about how often you (or the person you are evaluating) engage in the described behavior. indicate your response to each item by circling one of the five numbers to the right of each item.

Key: 1 = never 2 = seldom 3 = occasionally 4 = often 5 = Always

|

1. Tells group members what they are supposed to do. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

2. Acts friendly with members of the group. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

3. sets standards of performance for group members. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

4. Helps others in the group feel comfortable. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

5. Makes suggestions about how to solve problems. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

6. responds favorably to suggestions made by others. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

7. Makes his or her perspective clear to others. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

8. Treats others fairly. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

9. develops a plan of action for the group. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

10. Behaves in a predictable manner toward group members. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

11. defines role responsibilities for each group member. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

12. communicates actively with group members. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

13. clarifies his or her own role within the group. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

14. shows concern for the well-being of others. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

15. provides a plan for how the work is to be done. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

16. shows flexibility in making decisions. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

17. provides criteria for what is expected of the group. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

18. discloses thoughts and feelings to group members. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

19. encourages group members to do high-quality work. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

20. Helps group members get along with each other. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

scoring

The Leadership Behavior Questionnaire is designed to measure two major types of leadership behaviors: task and relationship. score the questionnaire by doing the following: First, sum the responses on the odd-numbered items. This is your task score. second, sum the responses on the even-numbered items. This is your relationship score.

Total scores: Task relationship

scoring interpretation

45–50 Very high range 40–44 High range

35–39 Moderately high range 30–34 Moderately low range 25–29 Low range

10–24 Very low range

The score you receive for task refers to the degree to which you help others by defining their roles and letting them know what is expected of them. This factor describes your tendencies to be task directed toward others when you are in a leadership position. The score you receive for relationship is a measure of the degree to which you try to make subordinates feel comfortable with themselves, each other, and the group itself. it represents a measure of how people oriented you are.

your results on the Leadership Behavior Questionnaire give you data about your task orientation and people orientation. What do your scores suggest about your leadership style? Are you more likely to lead with an emphasis on task or with an emphasis on relationship? As you interpret your responses to the Leadership Behavior Questionnaire, ask yourself if there are ways you could change your behavior to shift the emphasis you give to tasks and relationships. To gain more information about your style, you may want to have four or five of your coworkers fill out the questionnaire based on their perceptions of you as a leader. This will give you additional data to compare and contrast to your own scores about yourself.

Summary

The behavioral approach is strikingly different from the trait and skills approaches to leadership because the behavioral approach focuses on what leaders do rather than who leaders are. It suggests that leaders engage in two primary types of behaviors: task behaviors and relationship behaviors. How leaders combine these two types of behaviors to influence others is the central focus of the behavioral approach.

The behavioral approach originated from three different lines of research: the Ohio State studies, the University of Michigan studies, and the work of Blake and Mouton on the Managerial Grid.

Researchers at Ohio State developed a leadership questionnaire called the Leader Behavior Description Questionnaire (LBDQ ), which identified initiation of structure and consideration as the core leadership behaviors. The Michigan studies provided similar findings but called the leader behaviors production orientation and employee orientation.

Using the Ohio State and Michigan studies as a basis, much research has been carried out to find the best way for leaders to combine task and relationship behaviors. The goal has been to find a universal set of leadership behaviors capable of explaining leadership effectiveness in every situation. The results from these efforts have not been conclusive, however. Researchers have had difficulty identifying one best style of leadership.

Blake and Mouton developed a practical model for training managers that described leadership behaviors along a grid with two axes: concern for results and concern for people. How leaders combine these orientations results in five major leadership styles: authority–compliance (9,1), country-club management (1,9), impoverished management (1,1), middle-of-the-road

management (5,5), and team management (9,9).

The behavioral approach has several strengths and weaknesses. On the positive side, it has broadened the scope of leadership research to include the study of the behaviors of leaders rather than only their personal traits or characteristics. Second, it is a reliable approach because it is supported by a wide range of studies. Third, the behavioral approach is valuable because it underscores the importance of the two core dimensions of leadership behavior: task and relationship. Fourth, it has heuristic value in that it provides us with a broad conceptual map that is useful in gaining an understanding of our own leadership behaviors. On the negative side,

researchers have not been able to associate the behaviors of leaders (task and relationship) with outcomes such as morale, job satisfaction, and productivity. In addition, researchers from the behavioral approach have not been able to identify a universal set of leadership behaviors that would consistently result in effective leadership. Last, the behavioral approach implies but fails to support fully the idea that the most effective leadership style is a high–high style (i.e., high task and high relationship).

Overall, the behavioral approach is not a refined theory that provides a neatly organized set of prescriptions for effective leadership behavior. Rather, the behavioral approach provides a valuable framework for assessing leadership in a broad way as assessing behavior with task and relationship dimensions. Finally, the behavioral approach reminds leaders that their impact on others occurs along both dimensions.