Reading: Three Approaches to Coaching

Author: Jim Knight | Feb 3, 2021 |

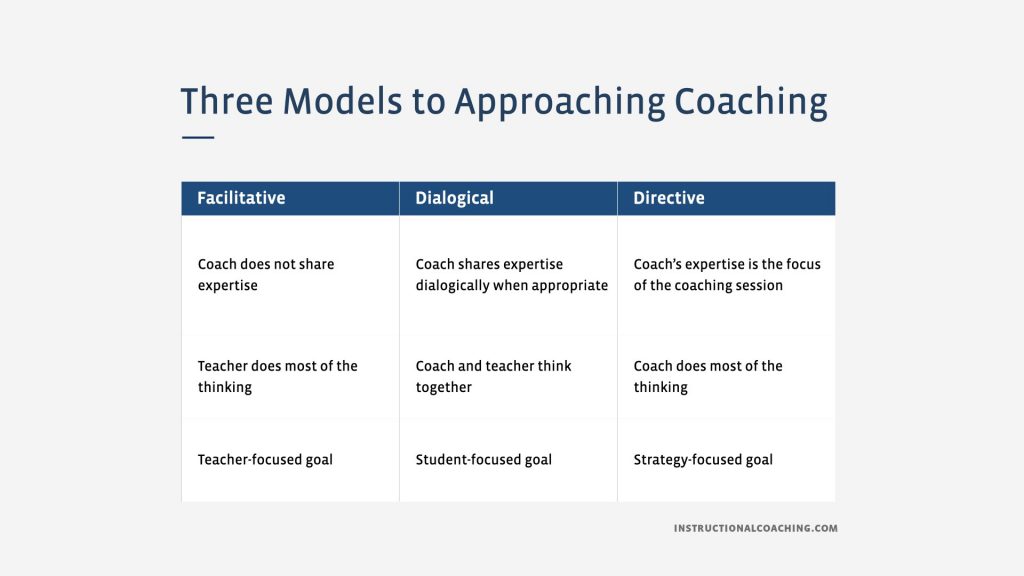

Instructional coaches implementing the Impact Cycle take a dialogical approach to coaching. The dialogical approach, as the table below illustrates, represents one of the three most common approaches to coaching, the other two being facilitative and directive coaching. Each approach has its unique strengths and weaknesses, and I have summarized each of them below.

Facilitative Coaching

Facilitative coaches, like dialogical coaches, see collaborating teachers as equals who make most if not all decisions during coaching. As Sir John Whitmore has written in his influential book Coaching for Performance: GROWing People, Performance, and Purpose (2002), “the relationship between the coach and coachee must be one of partnership in the endeavor, or trust, of safety and of minimal pressure” (p. 20).

Facilitative coaches encourage coachees to share their ideas openly by listening with empathy, paraphrasing, and asking powerful questions. Additionally, facilitative coaches do not share their expertise or suggestions with respect to what a teacher can do to get better. They keep their ideas and knowledge to themselves because they assume that:

- Coachees already have the knowledge they need to improve, so a coach’s role is to help them unpack what they already know.

- Coaches who share their expertise with coachees could inhibit progress by keeping coachees from coming up with their own solutions.

“The coach is not a problem solver, a teacher, an adviser, an instructor, or even an expert; he or she is a sounding board, a facilitator, a counselor, an awareness raiser” (p. 40). – Sir John Whitmore, Coaching for Performance (2002)

Facilitative coaching can be used in all kinds of situations, so it has the potential to address issues that dialogical and directive coaching are not able to address. For example, facilitative coaching could be used to help a teacher get along with a difficult team member, a principal lead culture change in her school, or a student use his time more effectively.

In the classroom, facilitative coaching works best when the teachers being coached already have the knowledge they need to improve. However, it is less effective when teachers do not have the knowledge they need to address issues in the classroom. A teacher who is struggling to create a learner-friendly classroom culture and who has not learned effective strategies for classroom management will likely need an instructional coach to help him master teaching behavioral expectations, reinforcing appropriate behavior, and correcting inappropriate behavior. Facilitative coaching, because it asks coaches not to share their expertise, is not an appropriate vehicle for schools or districts intending to use coaching to share instructional practices.

Directive Coaching

In many ways, directive coaching is the opposite of facilitative coaching. The directive coach’s goal is to help coachees master some skill or set of skills. The directive coach/coachee relationship is similar to a master/apprenticeship relationship. The directive coach has special knowledge, and his job is to transfer that knowledge to the coachee.

The relationship between the directive coach and teacher is respectful, but not equal. In contrast to facilitative coaches who set their expertise aside, the directive coach’s expertise is at the heart of this coaching approach. The job of the directive coach is to make sure teachers learn the correct way to do something, so directive coaches tell teachers what to do, model practices, observe teachers, and provide constructive feedback to teachers until they can implement the new practice with fidelity.

Directive coaches work from the assumption that the teachers they are coaching do not know how to use the practices they are learning, which is why they are being coached. Secondly, they also assume that teaching strategies should be implemented with fidelity, which is to say in the same way in each classroom. The goal of the directive coach is to ensure fidelity to a proven model, not adaptation of the model to the unique needs of children or strengths of a teacher.

The best directive coaches are excellent communicators, who listen to their coachees, confirm understanding with effective questions, and sensitively read their coachee’s understanding or lack of understanding. They need to especially be effective at explaining, modeling, and providing constructive feedback.

When teachers are committed to learning a teaching strategy or program, directive coaching can be effective. However, directive coaching, deprofessionalizes teaching by minimizing teacher expertise and autonomy and therefore frequently engenders resistance. Telling teachers they have to do something a certain way treats teachers more like laborers than professionals, and it often leads to resistance more than change.

The directive approach to coaching also often fails because it over simplifies the rich, complex world of the classroom. The unique, young human beings who attend our schools are too complex for one-size fits all approaches to learning. What teachers and students need is an approach to coaching that combines the facilitative coach’s respect for the professionalism of teachers with the directive coach’s ability to identify and describe effective strategies that can help teachers move forward. That approach is the dialogical approach.

Dialogical Coaching

The facilitative coach focuses on inquiry, using questions, listening, and conversational moves to help a teacher become aware of answers he already has inside himself. The directive coach focuses on advocacy, using expertise, clear explanations, modeling, and constructive feedback to teach a teacher how to use a new teaching strategy or program with fidelity. The dialogical coach balances advocacy with inquiry.

Like a facilitative coach, a dialogical coach embraces inquiry, asking questions that empower a collaborating teacher to identify goals, strategies, and adaptations that will have an unmistakable impact on students’ achievement and wellbeing. Dialogical coaches ask powerful questions, listen and think with teachers, and collaborate with them to set powerful goals that will have a powerful impact on students’ lives. They employ a coaching cycle, like The Impact Cycle, that is driven by back-and-forth conversation about current reality and a teacher’s desired reality in the classroom.

However, in contrast to facilitative coaches, dialogical coaches do not withhold their expertise. They work from the assumption that the issues teachers face in classrooms can often be better addressed if teachers look at what research has identified as effective teaching strategies. Therefore, like directive coaches, they have a deep understanding of teaching strategies they can share with teachers to help them improve. What separates them from directive coaches, however, is that they do not do the thinking for teachers. Instead, they position teachers as decision makers.

Dialogical coaches do not give advice; they share possible strategies with teachers and let teachers decide on which strategy they will use to try to meet their goals. Dialogical coaches partner with teachers to identify goals and teaching strategies, and then describe strategies precisely, while also asking teachers how they want to modify the strategies to better meet students’ needs. Then they help the teachers implement the strategies and gather data on whether or not they lead to students hitting their goals. Dialogical coaches don’t keep their ideas to themselves, but they realize that sometimes strategies have to be modified to meet students’ needs and to align with teachers’ strengths. They also understand that student-focused goals that matter to teachers are essential for effective coaching.

During dialogical coaching, the standard for excellent implementation—in contrast to directive coaching—is not the coach’s opinion but the goal itself. If a teacher implements a strategy in a way that is radically different from how it was designed to be used, the coach doesn’t take a top-down approach and tell the teacher how to teach the strategy with fidelity. The coach simply says, “Let’s see if we can hit the goal.” If the goal isn’t reached, then teacher and coach can go back to the description and consider whether or not the strategy should be taught with greater fidelity.

Facilitative and directive coaching both involve conversation, but they do not involve dialogue. A dialogue is a meeting of the minds, two or more people sharing ideas with each other. It is not a dialogue if I withhold my ideas, and it is not a dialogue when I tell you what you should do. It is a dialogue when I share my ideas in a way that makes it very easy for others to share their ideas. A dialogue is thinking with someone.