Reading: Post-traumatic Growth at Work

Author: Sally Maitlis

INTRODUCTION

Kevin began the trombone at the age of 10 and quickly knew that he wanted to become a professional musician. Working tirelessly, he won a scholarship to study at a top London conservatoire and soon after was offered the job as principal in a major British symphony orchestra, a dream come true. Kevin loved his work, as well as the camaraderie of orchestral life. His fine playing quickly came to the attention of other orchestras and the career possibilities appeared boundless. Very busy and looking to the future, Kevin did not pay much attention when his left shoulder began to hurt. The pain increased over many months, however, increasingly affecting his playing. Eventually, it became impossible for Kevin to ignore. He explained how, after a concert one evening, “I had this pain going right up my arm, into my shoulder, and right up into my face. I phoned [my wife] and I was in tears and said, ‘I think I’ve screwed myself up; I’ve really hurt myself.’”

Over the next two years, and with growing desperation, Kevin saw 30 different specialists, from physiotherapists to psychologists. But any improvements were short-lived and, despite working to completely relearn his technique, Kevin eventually had to accept that he could no longer continue as an orchestral musician. “I felt like I’d lost everything,” he shared. As he worked to come to terms with his situation, he tentatively applied for and was appointed to a senior management position at a well-regarded British conservatoire. Much to his surprise, Kevin soon found himself completely at home, and passionate about work in a whole new way. He described his work as:

"...an amazing opportunity to turn all the bad things that had happened to me into good ones.... I genuinely feel that those experiences have given me some irreplaceable tools for this job.... It’s a physical job in that I have to perform still—make music with the students. Also, there’s an incredible mental challenge every single day. There’s a need for real emotional empathy and understanding in my job as well.... At the moment, I’m using every single aspect of me, rather than just one very specialized aspect that actually needed quite a lot of maintenance to keep going.... I was a really good trombone player in a good orchestra, but I don’t think I was that much of a useful person. I was useful to myself but, yes, I feel much happier about me as a person now."

Kevin’s story, taken from my ongoing research on musicians and dancers who have faced a major disruption to their careers, is one of work-related post-traumatic growth. Although devastated by the injury that ended the career for which he had single-mindedly strived since childhood, he subsequently experienced himself as doing work that was an “amazing opportunity” that allowed him to use many more parts of himself, and to turn his painful experiences into good ones. Taking pleasure in being of service to others, Kevin also found his priorities had also shifted, a common facet of post-traumatic growth.

This review explores the phenomenon of post-traumatic growth at work. By examining studies of individuals like Kevin and the countless others who have encountered extremely difficult situations that significantly affect their work lives, we see a great many people emerge from work-related trauma stronger, with deeper connections to others, and with a clearer sense of what matters. This review explains when and how work-related post-traumatic growth occurs, building a model of the process through which it develops.

DEFINING AND CONCEPTUALIZING POST-TRAUMATIC GROWTH

Post-traumatic growth is the transformative positive change that can come about as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises. This positive change can take different forms. Tedeschi & Calhoun originally identified three, which have remained core in later work: perceptions of self, relationships with others, and philosophy of life. Thus, those who have survived a trauma may begin to see themselves as stronger and better able to deal with difficult events in the future (self-perception). They may also change how they see and feel around others, experiencing a greater sense of intimacy and belonging (relationships with others). Additionally, they may gain a greater sense of purpose and appreciation for life, and new priorities about what is most important (life philosophy). Subsequently, and with the development and widespread use of a self-report instrument, the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PGTI), many scholars have conceptualized growth in five domains: personal strength, relating to others, appreciation of life, openness to new possibilities, and spiritual change. The first three of these align with the original domains; new possibilities captures the new interests, activities, or paths that can open up for individuals following a trauma; and spiritual change reflects an engagement with spiritual, religious, or existential matters.

Various terms have been used to describe the experience of positive change after adversity, including stress-related growth, perceived benefits, positive adaptation, and adversarial growth. All are used to capture broadly similar kinds of changes, although different studies and measures emphasize slightly different facets of growth.

Origins of Post-traumatic Growth

The term 'post-traumatic growth' appeared in the literature approximately 25 years ago, but the idea that positive change can emerge from pain and suffering is much older. This theme runs through the writings of the major world religions, in which the power of very difficult experiences to transform can be found in the writings of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. It is a central motif within literature, music, and other cultural forms, and it underpins existential and other psychological perspectives on human suffering. In the scholarly psychology literature, an interest in the nature of posttraumatic growth, the kinds of catalytic events that prompt it, and the factors that enable it has grown rapidly in the past two decades. It has received much less attention in management writings, and only a relatively small number of studies have considered post-traumatic growth in the context of work and organizations.

Post-traumatic Growth as Outcome and Process

Post-traumatic growth can be understood as both a process and an outcome. As an outcome, it is seen as a state achieved as the result of a set of psychological and behavioral change processes. Post-traumatic growth is also regarded, especially in narrative and other processual ontologies, as a process of change. Each perspective is discussed below.

Post-traumatic growth as outcome. Most empirical research has treated post-traumatic growth as an outcome, an experience of positive change occurring through the struggle with significant adversity. Many early studies revealed the presence of post-traumatic growth in the aftermath of a wide range of largely personal traumatic events, such as the death of a child or a cancer diagnosis. In this and subsequent work, post-traumatic growth has typically been measured by benefits found, meaning made, or perceived growth on the PGTI or other self-report instruments.

In parallel with this research, inductive, qualitative studies of post-traumatic growth have allowed the identification of some growth experiences following adversity not fully captured by current scales, such as a new awareness of the body, in the case of illness-related post-traumatic growth. Furthermore, amid questions about the conceptualization and operationalization of post-traumatic growth, some studies have examined the construct of growth together with that of psychological well-being, seeking convergence across these constructs.

Because growth is almost always self-reported, one could argue that the literature explores individuals’ perceptions of having grown, rather than growth itself. Like psychological well-being, however, post-traumatic growth is an inherently subjective experience, and attempting to assess it in some objective sense is therefore problematic. We return to these issues in the final two sections of this review, Challenging Issues in the Study of Post-traumatic Growth, and Future Directions for Research.

Post-traumatic growth as an outcome is theorized to be the result of a process that involves making meaning of what has happened, coping with distress, and other related activities such as self-disclosure and acceptance. Although research has found relationships between individuals’ reports of such endeavors (e.g., that they have come to terms with the event) and their reports of growth, less work has directly investigated the process through which post-traumatic growth develops, which may be seen as the process of post-traumatic growth.

Post-traumatic growth as process. Narrative scholars are among those who regard post-traumatic growth as a process, one through which new, growthful narratives are developed. For example, post-traumatic growth has been described as “a form of meaning reconstruction in the wake of crisis and loss” or the “process of constructing a narrative understanding of how the self has been positively transformed by the traumatic event”. Such research highlights the process through which individuals story themselves in new ways, including acknowledging the trauma’s emotional impact, analyzing its effect on and meaning for the self, and constructing a positive ending that explains the self-transformation.

Other studies explore the identity work in which people engage as they shift their focus away from threatened or diminished understandings of themselves and begin to develop new, growthful identities. This process involves activities such as reducing the importance accorded to a previous identity while strengthening a new one, and creating a transitional identity that enables individuals to move gradually from who they were pre-trauma to a positive construction of who they might become post-trauma. We return to the process of post-traumatic growth and explore it more fully in the section Theorizing the Process: A Model of Post-traumatic Growth at Work.

The Relationship Between Post-traumatic Growth and Post-traumatic Stress

The relationship between post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress is complex and still unclear. Although we might imagine that post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress are opposite ends of a spectrum, this is not the case. They are orthogonal constructs, and post-traumatic stress, or at least some considerable degree of distress and psychological disruption, is a prerequisite for post-traumatic growth, given that experiencing trauma is highly distressing and growth comes through struggle. Thus, post-traumatic growth cannot occur instead of post-traumatic stress after a traumatic event, but only in addition to it, driven by a distressing challenge to individuals’ assumptions and core beliefs. Research on the relationship between post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth has produced mixed findings, with some studies showing greater post-traumatic stress is associated with greater post-traumatic growth, and others either a negative or an inverted U-shaped relationship, with the highest levels of growth occurring at moderate levels of stress. Some recent longitudinal studies have found a positive relationship between post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth over time, such that initial levels and increases in post-traumatic stress predicted increases in post-traumatic growth. This work suggests that growth may not only be facilitated but may also be maintained by the presence of posttraumatic distress, perhaps because feeling distress prompts continued efforts to make new meanings and to move forward, which in turn are associated with growth experiences.

Distinguishing Posttraumatic Growth from Related Concepts

In addition to terms such as adversarial or stress-related growth, often used interchangeably with post-traumatic growth, there are several different concepts that are sometimes confused with post-traumatic growth, including resilience, recovery, thriving, and flourishing. Resilience is commonly understood as the ability to maintain relatively stable, healthy levels of functioning after a highly disruptive event or the maintenance of positive adjustment under challenging conditions. Thus, resilience can be seen to differ from post-traumatic growth in that it emphasizes stability in the context of trauma, rather than a trajectory of in- creased positive functioning. Recovery is also different in that it involves a return to prior levels of functioning after a crisis, rather than a trajectory of increased functioning.

Thriving has been defined as “the psychological state in which individuals experience both a sense of vitality and a sense of learning”. Although thriving is associated with growth, it is more often understood as an everyday occurrence and is not normally linked to traumatic or significantly adverse experiences. As with thriving, flourishing is a broader term associated with well-being. Flourishing individuals are “filled with emotional vitality...functioning positively in the private and social realms of their lives”. Thriving, flourishing, and post-traumatic growth all involve individuals’ positive functioning at a level beyond normal expectations. In post-traumatic growth, however, this occurs only in the aftermath of significant adversity, whereas in thriving and flourishing it may or may not occur after a negative event. Furthermore, post-traumatic growth entails transformation, in a way that is less prominent in thriving or flourishing, and this transformation comes through the struggle with significant adversity.

Traumatic Experience Prompting Post-traumatic Growth

Research suggests that growth is a common experience for individuals after a deeply distressing incident. In general, prevalence has been found to lie between 30% and 70%, depending on the trauma, sample, and way that post-traumatic growth is assessed. In the workplace, studies of inherently traumatizing occupations such as the military and emergency services report prevalence rates of 40–75%. No data are available for post-traumatic growth in “ordinary” work.

Personal Experiences

Post-traumatic growth has been found in the aftermath of a myriad of different kinds of traumatic events. Although a few studies have examined differences across types of trauma, in general, it has been argued that the nature of the event itself is less important for post-traumatic growth than the way that an individual experiences it. Research to date has explored post-traumatic growth after personal losses such as bereavement, medical problems, and interpersonal violations, such as rape and other forms of sexual assault. Post-traumatic growth has also been studied following various community traumas, such as natural disasters and terrorism. In each case, individuals were found to have experienced growth following intensely painful trauma, irrespective of the kind of trauma they had encountered, or whether it was a one-off event or an ongoing problem.

Experiences in Work and Affecting Work

Despite the expansion of research on post-traumatic growth over the past two decades, the literature on post-traumatic growth at work and organizational life remains surprisingly small—a gap that is problematic for at least three important reasons. First, many personally traumatic events can have a significant impact on people’s ability to do their work and on their feelings about that work. Second, trauma is often present in organizational life; experiences including redundancy, restructuring, bullying, and ethical violations can be deeply distressing. Furthermore, jobs may demand “necessary evils” that involve causing emotional or physical harm, and that can be traumatic for both the deliverer and the recipient. Third, the increasing precarity of work carries with it a greater potential for affected individuals to experience work-related events as traumatic. The relatively small body of research that explores post-traumatic growth at work has emerged out of a larger literature on traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in certain job contexts vulnerable to trauma and now forms three distinct streams of research.

Inherently traumatic work. The largest of these examines post-traumatic growth in settings where jobholders encounter trauma as a matter of course, including the military, police, emergency services, and disaster/rescue work. Together, this research shows that although doing such work often leads to post-traumatic stress and PTSD, it can also prompt post-traumatic growth. These studies find that job holders are more likely to experience post-traumatic growth if they encounter a severe threat, and one directed at them, rather than witnessing threat or harm to others. Post-traumatic growth is also more common if someone working in an inherently traumatic profession experiences a threat from multiple sources, or witnesses a death, especially that of a friend. One study of emergency ambulance officers finds that post-traumatic growth may also be greater for workers who have experienced a personal trauma in addition to a work-related trauma. This literature indicates that work-related post-traumatic growth is most likely following the most devastating and personally distressing workplace experiences, and especially if these occur alongside adversity in individuals’ personal lives. The research on inherently traumatic work thus seems to support research discussed earlier in this review, showing post-traumatic growth is greater when post-traumatic stress is more severe.

Secondary trauma at work. The largest body of work-related post-traumatic growth research is that on secondary or vicarious trauma and growth in professionals whose work can be traumatizing because it involves supporting others who have been traumatized. This research includes studies of health professionals such as labor and delivery nurses and psychotherapists, social workers, interpreters, clergy, and funeral directors. It shows how individuals working with the trauma of their clients can incur secondary traumatic stress but also often experience secondary posttraumatic growth. In many of these cases, post-traumatic growth is linked to the change and growth that workers witness in their clients, which prompts in those workers a new appreciation of what is possible, in terms of the difference they can facilitate, and in some cases it may prompt a spiritual broadening. Empathy is important here because workers are more likely to experience secondary post-traumatic growth if they feel empathically engaged with their clients. Thus, witnessing post-traumatic growth in others can itself be positively transformative.

Trauma in “ordinary” work. Finally, a few studies explore the possibility of post-traumatic growth in the context of “ordinary” work. Most of these investigate disruptions to work, such as losing a job or being unable to continue in work because of injury. In contrast, only a few studies have examined growth that followed from adversities that require coping while doing one’s job. This research has highlighted a range of experiences, including a denied promotion, abusive supervision, and whistle-blowing retaliation. Post-traumatic growth following these experiences can take different forms, often behavioral, such as feeling inspired and empowered to establish conditions for employee voice and greater compassion for patients.

Despite the small number of studies, the qualitative methods often employed have led to rich insights into the impacts of adversity, as well as identifying novel forms of post-traumatic growth. We thus learn that losing a job or being unable to continue in a career can challenge core beliefs about identity, causing distress and confusion, but also creating opportunities for post-traumatic growth in the form of broadened or new identities, deeper self-understanding, and a greater personal strength and independence. In their study of refugees, Wehrle found that the difficult, undermining, and lonely experiences of job-seeking enabled learning, through which refugees came to see themselves as stronger and more confident and underwent shifts in their sense of what was important.

Research on growth resulting from a combination of personal and work-related adversity shows, for example, how athletes can be mobilized by significant setbacks and make growthful meanings of their experiences (e.g., finding joy in helping others) that allow them to take pleasure in new identities, activities, and relationships. Other research has shown how traumatic experiences can enable growth in individuals’ leadership capacity, in many cases for a cause connected to their own trauma. For example, Kevin, whose story begins this article, now talks passionately to young musicians about looking after their physical and mental health, and recognizing when they need help—something he himself was slow to do.

Summary

Research shows that growth can occur in people doing jobs that are inherently traumatic (directly or vicariously), but we have limited understanding of when such work-related post-traumatic growth is more likely or the processes through which it occurs. Additionally, relatively little is known about post-traumatic growth in “ordinary” work. Research on growth following work-related adversity has tended to examine it in individuals outside of an organizational setting, either because they have lost jobs, are attempting to get a job, or do work independently of an organizational role. Thus, although we know that organizational practices and relationships contain many potential resources for growth, these have received little attention in work-related post-traumatic growth research.

Figure 1: A model of post-traumatic growth at work. Post-traumatic growth at work is sparked by a traumatic work-related event that disrupts individuals’ assumptive worlds and leads to dysregulated cognitions and emotions. Growth occurs through a recursive cycle of emotion regulation and sense-making that is enabled by social support, occupational support, and attentive companionship. Post-traumatic growth can then lead to enhanced well-being, positive physiological changes, and a variety of work-related outcomes such as a positive work identity, career proactivity, and prosocial leadership.

THEORIZING THE PROCESS: A MODEL OF POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH AT WORK

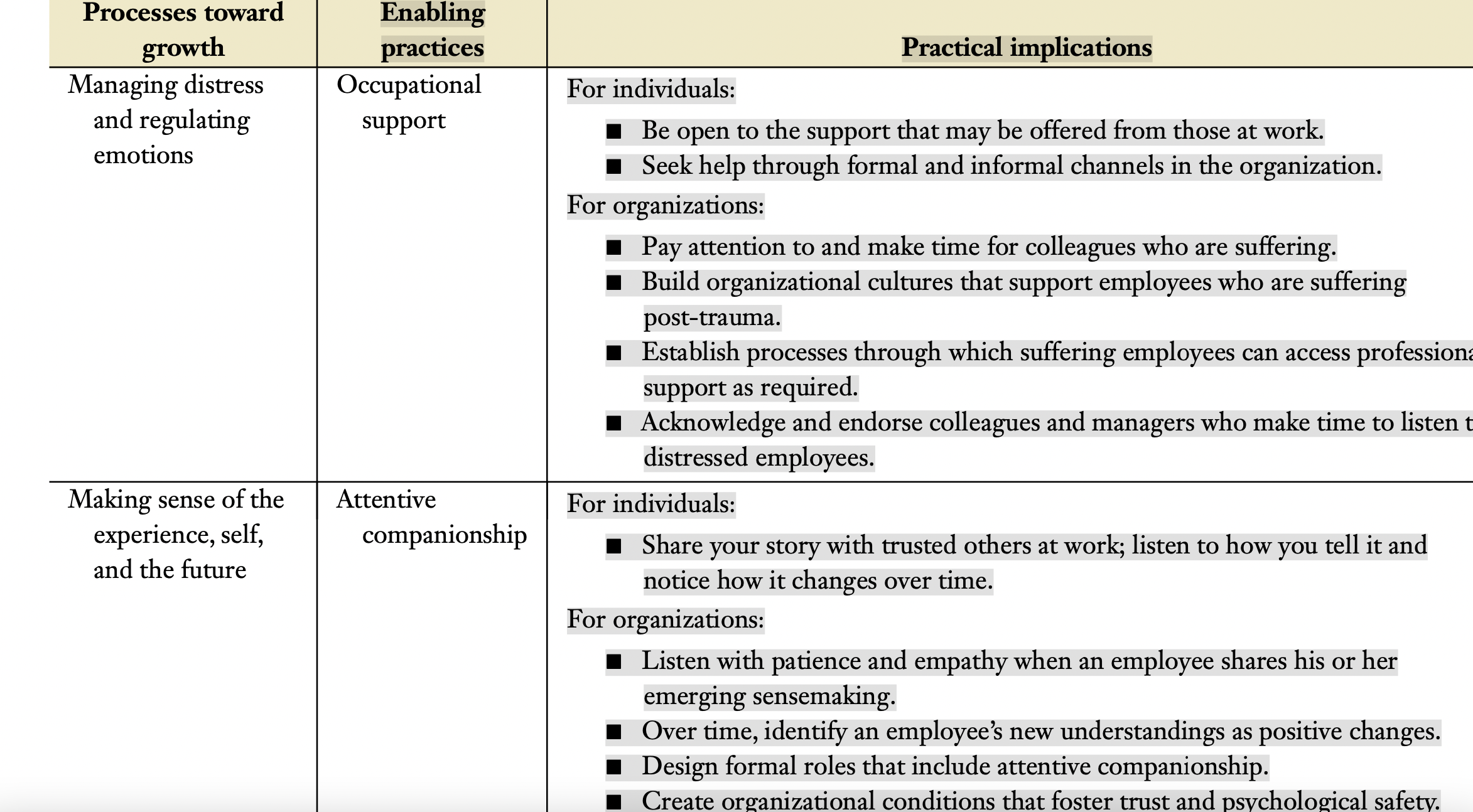

This section elaborates on the process through which posttraumatic growth at work develops, as Figure 1 illustrates. Table 1 provides a summary of the practical implications of this model, which are raised throughout the section.

Triggering Event Disrupts Existing Understandings and Prompts Emotional Response

Underpinning writing on post-traumatic growth is the notion that such growth is prompted by a negative event that significantly disrupts important understandings a person has about the world and themselves in the world. These understandings, known in the posttraumatic growth literature as the assumptive world, are central to our feelings of security. An experience that challenges them is frightening and confusing, shattering the sense that the world is predictable, knowable, and largely controllable. The clinical literature explains that what makes a traumatic event so devastating is its impact on individuals’ deep assumptions and feelings of safety in the world. Because of this emotional impact on a fundamental sense of safety and security, Figure 1 includes within assumptive world both core beliefs (our cognitive understandings about the world) and emotional security (our feeling of ease and safety in the world).

In the period immediately following a trauma, individuals experience repeated invasive memories, images, and unwanted thoughts that are very difficult to manage or stop. This pattern reflects the brain’s efforts to integrate the traumatic event into existing schema, but it is involuntary and usually very distressing, exacerbating the painful emotions of the event itself. In the case of normal adaptation (rather than progression to PTSD), the frequency and intensity of traumatic memories diminish and the individual becomes more emotionally regulated over a period of several weeks.

Disrupting assumptive worlds at work. Studies of trauma in the workplace highlight how jobs involving combat, disaster work, and trauma work often challenge workers’ assumptions about humanity. For example, when soldiers go to war or counsellors hear the stories of those who have been traumatized, this can significantly undermine their beliefs about benevolence and justice, causing feelings of distress and hopelessness. But even in organizations not directly engaged in traumatizing work, employees may encounter many experiences that shatter their assumptions and emotional security. For example, experiences of major organizational change, redundancy, sexual harassment, or abusive supervision can subvert employees’ beliefs about themselves, their organization, and their place in it. At a collective level, employees may be thrown into shock and distress by an event that affects the organization as a whole, as was the case in BP with the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and the many institutions affected by the terrorist attacks of 9/11—“strong events” in event system theory. Such potentially traumatic incidents can create deep distrust; raise doubts about others’ intentions and one’s own capabilities; and prompt feelings of fear, anger, anxiety, and even guilt and shame.

Organizational conditions influencing disruption. Certain organizational characteristics in- crease or decrease the likelihood that an adverse event will disrupt the assumptive world of one or more employees. For example, high reliability organizations strive to ensure a resilient response in the face of adversity by creating a mindful infrastructure that enables employees to anticipate and manage the unexpected through their everyday operations. Those working in such organizations are less likely to be surprised by something untoward, because they will already anticipate that possibility. Other organizations are underpinned by sets of values and cultural assumptions that make their employees more vulnerable to adversity. For instance, in a social enterprise with a core value of social good, employees will be shocked, confused, and per- haps angry if an action is taken that violates these ideals, and their own assumptive worlds, as seen in the Oxfam Haiti sex scandal. This can also happen in a corporation experiencing an ethical breach, as in the Volkswagen emissions exposé, or in an occupation such as law or medicine when clear professional norms are violated. But the extent to which individuals’ world views are chal- lenged depends on a disparity between the incident and the values and assumptions that underpin the organizational or professional culture, as well as the strength of that culture. And, as with any potentially adverse event, people will be differentially affected: Those who identify strongly with their organization or profession are more likely to experience such incidents as traumatic.

Managing Distress and Regulating Emotions

Following a trauma, emotions such as anxiety, sadness, anger, and guilt can be overwhelming and hard to control, making it difficult to function in the world. Survivors are also hypersensitive to reminders of the traumatic event, which can prompt strong emotional reactions that may seem to come out of nowhere. Emotion regulation, or the ability to modulate and manage emotional experiences, is greatly compromised by trauma, significantly due to the increased levels of cortisol and adrenaline that come as a result of the body functioning in “threat” mode even after a traumatic event is over. This inability to self-regulate is one of the most far-reaching effects of trauma, also affecting individuals’ cognitive capacity to focus and concentrate on other things.

However, in order to process their experience and move on, individuals need to be able to manage their distress and regulate their emotions, so that they can function without ongoing disruption from pervasive negative feelings and their debilitating effects. Doing so also makes possible a shift away from the intrusive thoughts, memories, and images that dominate the early period after a traumatic experience toward a more generative sensemaking process in which survivors can start to make meaning of what has happened. Social support is a key enabler in this process.

Social support as an enabling mechanism. Research consistently shows the value of social support in helping people regulate their emotions. Such support can come from family, friends, colleagues, or formal support groups, and covers a range of possibilities, including having someone with whom to discuss problems, share joy and sorrow, count on when things go wrong, and get practical help. Social support has repeatedly been found to be important in the development of posttraumatic growth, for example, in cancer survivors who can talk with supportive others about their diagnosis, or in survivors of interpersonal violence who receive a non-blaming response from those to whom they disclose their experience. The timing of the support seems to matter: Some studies suggest that support, especially emotional, is more valuable in the earliest period after a trauma than in later stages.

Occupational Support. When people experience a trauma that affects their work, they may get support from various relationships. Social support often comes from employees’ families and friends, but the work environment has the potential to provide other valuable sources. This is known as occupational support and can play a critical, and particularly pertinent, role in helping workers cope with work-related crises. Some studies of post-traumatic growth in the workplace distinguish between social support from friends and family and occupational support, whereas others ask more generally about social support without specifying the source. Such research has found a relationship between support and post-traumatic growth in a range of work contexts, including emergency medical dispatchers, firefighters, the military, trauma workers, and athletes.

Recent research on compassionate organizations and companionate organizational cultures further corroborates the benefits of work environments in which people feel supported and cared for. Such studies show that in organizations where employees are treated with care and compassion as they face significant challenges, they feel more job satisfaction and commitment, and experience less burnout and absenteeism. In organizations where such values are not built into the culture, social support may be provided by so-called toxin handlers. This is not without cost, however: These empathic managers, who try to alleviate suffering in their workplaces, can end up absorbing the toxicity and falling prey to compassion fatigue and burnout. In sum, occupational support, deriving from supportive work relationships and enabled by supportive organizational cultures, plays a powerful role in helping trauma survivors manage their distress and regulate the difficult emotions that follow a traumatic experience.

Sensemaking About the Traumatic Event, Oneself, and the Future

Sense-making is a meaning-making process through which people work to understand unexpected or confusing events. It is prompted by some kind of interruption to the ongoing flow, such as an event or incident that contravenes people’s expectations and leaves them uncertain as to how to behave. Experiencing a trauma that disrupts one’s assumptive world is such an event. Yet it is hard to make sense of things when flooded with emotion, which is why the sense-making process can only begin once people are functioning at a lower level of emotional arousal. As a more deliberate and generative process, sense-making contrasts with the uncontrollable and intrusive thoughts and memories that immediately follow a trauma, although the two may also co-occur for a period.

A large body of research on post-traumatic growth and related literatures has identified sense-making as central to the development of post-traumatic growth. Sometimes referred to as “deliberative rumination”, this process involves searching for and creating meaning in the aftermath of a traumatic event. Finding ways to make sense of something difficult and unexpected can make it feel more predictable and controllable, and can allow people to regain a feeling of security. Moreover, when the meaning made involves elements such as growth in personal strength, a sense of greater belonging, or an increased appreciation for life, this can be understood as post-traumatic growth.

Sense-making as cognition. Sense-making after a trauma has an important cognitive dimension, including strategies such as positive cognitive restructuring (e.g., “There is ultimately more good than bad in this situation”), downward comparison (“Other people have had worse experiences than mine”), and acceptance (“I have come to terms with this experience”). Other cognitive ways of making meaning include assigning responsibility for the event, interpreting the experience through spiritual beliefs, or identifying positive consequences of the event.

Sense-making as action. Sense-making is also action-oriented, as individuals often understand the world through insights gained as a result of actions taken. Thus a person may come to understand her personal strength after adversity by noticing she is coping better than expected. This is consistent with Hobfoll’s interest in action-focused growth, emphasizing how meaning is found in action. In their work on post-traumatic growth in the context of terrorism, Hobfoll et al. argue that “real” post-traumatic growth comes not merely by thinking differently but by actualizing these cognitions through action. This, they believe, restores people’s sense of competence, autonomy, and attachment as well as embeds post-traumatic growth-enhancing practices in everyday living.

A body of research that has found prosocial behavior often follows trauma exposure can also be understood in this light. Here, traumatized individuals adopt an active stance in response to what they have been through, behaving in prosocial ways that make things better for others. It is thought that such responses may be motivated by a need to create meaning in a world that no longer makes sense, as, for example, after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Several of these studies involve disaster response workers and police officers who report feeling they have grown in various ways as a result of their active involvement in recovery and relief efforts after a crisis. In another example of how action enables the making of new sense, an interesting stream of research shows how physical exercise can lead to post-traumatic growth by bringing a sense of mastery for those whose trauma involved injury or illness.

Sense-making as narrative. Sense-making following a trauma can occur through the construction of narratives of positive transformation. Research in this tradition shows how growth can emerge in survivors’ stories of trauma, and themselves after a trauma. Such growth-oriented narratives are often developed and enriched in conversation with others, highlighting another way in which supportive others enable post-traumatic growth. But writing narratives about one’s thoughts and feelings following an adverse event has also been shown to be a powerful means of sensemaking, especially when produced over multiple occasions.

Sense-making after a work-related trauma. There is considerable research showing the importance of sense-making following a traumatic event in the context of work. For example, in a systematic literature review of post-traumatic growth in the military, Mark et al. found post-traumatic growth in veterans was predicted by sense-making. A study of US firefighters found that sense-making in the form of problem-solving and emotion-focused coping was positively related to post-traumatic growth, whereas disengagement coping (the very opposite of working to make sense of what has happened) was positively related to post-traumatic stress symptoms. There is also evidence for the role of sense-making in facilitating secondary post-traumatic growth in those who work with traumatized individuals. A systematic literature review of secondary post-traumatic growth found workers who were supported by psychotherapy were more likely to report growth, likely because of the opportunity that therapy provides to make meaning.

Sense-making is also important in facilitating growth in work environments where one would not normally expect to encounter trauma. In their narrative study of job loss, for example, Gabriel et al. depict the sense-making process as “narrative coping,” reflecting the struggle to construct a story of what has happened that offers both meaning and consolation. This involves creating a narrative in which unemployed professionals give voice to their difficult experiences and emotions, turning the trauma of redundancy into a prompt for refashioning identity. In a similar vein, Vough et al. explored narratives of retirement, identifying the sense-making that produced more and less growthful narratives of the ends of individuals’ working lives. A narrative analysis of the biographies of leaders of prosocial change found that individuals made sense of earlier traumas by engaging in trauma-inspired prosocial leadership that reflected a growth in their perspective and capacity to understand problems, as well as the development of more compassionate connections with others.

Attentive companionship as an organizational enabler of growth-oriented sense-making. Although social and occupational support are helpful in managing distress and regulating emotions after a traumatic event, a different kind of support—attentive companionship—enables sense-making for work-related post-traumatic growth. Attentive companionship derives from the concept of expert companionship, which developed out of writing for clinicians and combines clinical expertise with the human companionship that is so important for those who are suffering. Such a role can also be taken by nonclinicians, indi- viduals who are not expert therapists but who bring patience, empathy, and the capacity to listen well. In this sense, they are attentive, rather than expert, companions.

Key to this role is that the companion supports and may facilitate growth-oriented sense-making in an individual after a trauma, but does not try to create or induce it. Post-traumatic growth comes about through the struggle to make sense of a deeply testing experience; it cannot therefore be done to or given to another. Supporting this process means following the lead of those suffering, entering into the way they think and talk, and listening to their sense-making without trying to produce answers. This may involve listening to multiple tellings of the trauma story and responding appropriately to the accompanying emotions.

The attentive companion’s role is to listen out for times when the survivor mentions new understandings or possibilities, and, as appropriate, and usually not early in the post-trauma process, label these as positive changes. Of course, this is a highly sensitive matter, for it can be shocking, disturbing, and guilt-inducing to discover that one can have positive thoughts and feelings in the aftermath of terrible adversity. But, done with care and caution, this is a facilitative part of the pro- cess and can allow an individual to start building a new narrative of the event and its place in his or her life. In the context of work, an interpersonally sensitive manager, peer, or other coworker can be an attentive companion. In some organizations, certain formal organizational roles may include this type of support, for example, patient advocates in healthcare. It is crucial, however, that meanings labeled as positive changes are linked not to the trauma itself, but to the individual’s struggle and personal shifts in its aftermath. Making light of a traumatic event and its impact is not a path to post-traumatic growth.

Certain organizational conditions will support the presence and actions of attentive companions at work. For example, these relationships are rooted in a base level of trust and are more likely to exist and flourish in conditions of psychological safety. If employees fear the consequences of sharing what they are going through after a trauma, it will be harder for a caring colleague to facilitate their sensemaking. Trust and psychological safety, in turn, are more likely in organizations where there is a reasonable level of stability in the workforce, and in individuals’ roles. If turnover is high, or people are constantly changing roles and areas, they are likely to know less about each other, including the personal difficulties that someone is working through. Several practical implications follow, as Table 1 summarizes.

Outcomes Associated with Posttraumatic Growth

Several psychological, behavioral, and physiological outcomes are linked to post-traumatic growth, all with relevance to working life. Research has also begun to explore the relationship between post-traumatic growth and specific work- and career-related outcomes.

Well-being. In a meta-analysis of 87 cross-sectional studies relating post-traumatic growth to health outcomes, growth was found to be positively related to measures of well-being, including self-esteem and life satisfaction; negatively related to depression; and unrelated to anxiety, global distress, quality of life, and subjective physical health. A few cross-sectional studies have explored the positive association between post-traumatic growth and health- promoting behaviors, such as lower levels of substance use, suggesting a possible mediating mechanism for the growth–well-being relationship. Some longitudinal studies of cancer-related post-traumatic growth and health-related quality of life, a measure of mental well-being, also find a positive relationship. In a study of post-traumatic growth after sexual assault, Frazier et al. found that early reports of positive change that were maintained over time were related to less distress a year later. In contrast, a 17- year study of former prisoners of war did not find a relationship between earlier post-traumatic growth and later PTSD. In general, however, it appears that reports of growth, especially when maintained, predict better subsequent well-being.

Physiological outcomes. A small but important set of studies has explored the relationship between perceived post-traumatic growth and physiological outcomes. Research has found a link between breast cancer–related post-traumatic growth and reductions in serum cortisol, a hormone normally released in response to stress and that suppresses the immune system, and to increases in lymphocyte proliferation, an immune function protecting against breast cancer progression and recurrence. Similarly, studies of men with HIV found a relationship between post-traumatic growth and CD4 T-cell counts, a measure of immune system functioning, and between growth and lower rates of AIDS-related mortality. A study of hepatoma patients linked post-traumatic growth to higher peripheral blood leukocytes and a 186 day longer average survival time. These studies do not establish causality, but they show that post-traumatic growth is associated with positive changes in immune functioning over time, with positive implications for people suffering from potentially terminal diseases.

A novel study using functional fMRI techniques that investigated the relationship between post-traumatic growth and neural functioning found a positive association between growth and functional connectivity in parts of the brain that are associated with mentalizing, the ability to reason about the mental states of oneself and others. This is consistent with the relational facet of post-traumatic growth, and with research suggesting increased empathy in those who have experienced growth after adversity.

Work-related outcomes. A review of research on post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organizations reports that disaster workers who experience post-traumatic growth tend to feel they have gained in self-esteem, a sense of accomplishment and meaningfulness in their work, and a better understanding of their work. Other research has explored the effects of posttraumatic growth on identity outcomes. For example, Maitlis shows how post-traumatic growth leads to the development of new, positive identities in musicians who experienced a career-ending injury, a finding consistent with research suggesting employees who experience growth are more likely to develop resilient career identities and career proactivity. Other writing on abusive supervision theorizes that workers who experience posttraumatic growth may gain in confidence about what they can do, pursue new roles and vocations, and en- gage in positive leadership behavior toward others.

CHALLENGING ISSUES IN THE STUDY OF POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH

With the development of the study of post-traumatic growth over the past two decades have come challenging questions. Of particular importance are issues surrounding the veridicality of posttrau- matic growth—whether individuals truly grow after adversity, or if they simply want to believe (or want others to believe) that they have grown. A second key question concerns societal pressures for personal growth, particularly in certain cultures, and the resulting imperative to find the silver lining even in completely devastating circumstances.

Do People Grow?

Probably the most fundamental challenge to the area of post-traumatic growth comes from questions about whether perceptions of having grown constitute “real” growth. This in part reflects differences in how growth is conceptualized, either as understanding oneself as having grown, or as some more objectively measurable shift from one state to another. But there are also other positions alongside these stances. One is the argument, consistent with research on positive illusions, that believing one has grown after an adverse experience is a cognitive reappraisal strategy, typically unconscious, that helps people regain their sense of self-esteem and control. Research has shown that positive illusions can be adaptive and enhance well-being, an idea that links to a second set of arguments, that post-traumatic growth, or the process of finding benefits and growth in what has happened, is an effective coping strategy. However, research that finds that post-traumatic growth is not consistently related to well-being, mood, or distress raises questions for some about the veridicality of post-traumatic growth.

Emerging from this debate are proposals for the existence of different kinds of post-traumatic growth: illusory versus constructive growth, perceived versus actual growth, and post-traumatic growth versus quantifiable change. Yet others maintain that finding quantifiable evidence of growth is less important than an individual’s sense of having gained and grown. Indeed, those working within a phenomenological or narrative tradition give primacy to individuals’ lived expe- rience and the stories by which they live. Narrative scholars have long argued that “we become the autobiographical narratives by which we ‘tell about’ our lives”. From this perspective, then, a story of post-traumatic growth has enormous power, and is likely to engender further change. Although these different positions are not necessarily reconcilable, longitudinal research, which is still quite rare in the study of post-traumatic growth, may be able to bridge some of these gaps. We return to this in the Future Directions for Research section.

Should People Grow?

An important issue concerns the potential danger of expecting that growth will or even should follow adversity. Western cultures champion strength, invulnerability and independence; we want to see people overcome their challenges, transcend, and grow from adversity. This is perhaps especially the case in North America, where some note the “tyranny of the positive attitude” and argue that the relentless promotion of positive thinking leads to self- blame and a focus on eliminating negative emotion. People facing significant adversity may, in addition to experiencing distress, thus feel a pressure to find growth in their pain. Cordova, for example, notes that individuals diagnosed with cancer are often beseeched to “stay positive” and “look on the bright side,” sometimes with the suggestion that keeping a positive outlook may protect against the cancer. Although this may feel empowering, it can also be burdensome for those dealing with a life-threatening trauma.

Indeed, a recent study of patient adaptation to disability found that hoping for a reversal was associated with poorer life satisfaction and quality of life than was acceptance of the condition. In this case, hope seemed to prevent individuals from fully facing their difficult situation, and potentially also from growing. More generally, if survivors feel normative pressures to be growing, their distress, despair, and feelings of inadequacy are likely to increase. As noted in the earlier discussion of attentive companionship, there exists a fine line between supporting emergent post-traumatic growth and intervening to bring it about. Although an ideology that venerates the positive may be enlivening, it can also turn growth into a destination that all are expected to reach.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH

Post-traumatic growth has been the subject of research for more than two decades. Hundreds of studies have shown that people experience growth after struggling with significantly adverse events and have identified important factors that enable it to happen. There is, however, a real dearth of research on post-traumatic growth in the context of work. Existing studies have focused primarily on military and other “trauma-rich” contexts, or have explored secondary trauma in professions oriented toward helping the traumatized. There is an enormous opportunity for research on post-traumatic growth in ordinary kinds of work, where employees do not expect, but often encounter, highly adverse experiences. Below, I highlight critical methodological considerations and explore some important new questions for the study of work-related post-traumatic growth (see Table 2).

Methodological Imperatives

Looking ahead, we can take methodological lessons from extant research, using research designs and approaches that overcome the limitations of many previous studies. Studying work-related post-traumatic growth thus provides the chance to examine growth prospectively and longitudinally, to explore it in a wider range of cultural contexts, to use multiple measures of growth, and to gather assessments of growth both from individuals after adversity and from those close to them. These ideas are elaborated further below.

Longitudinal research. One of the greatest limitations of existing work on post-traumatic growth is the dearth of prospective and longitudinal studies. To date, the field has been dominated by cross-sectional studies in which growth is assessed retrospectively by asking participants how much they think they have grown since an adverse event. There are several reasons why this may be a problematic measure of growth; more generally, one cannot assess change or causality through cross-sectional research. Although the number of longitudinal studies of post-traumatic growth is increasing, few have prospective designs (taking measures prior to the adverse event). The challenges of doing prospective research on post-traumatic growth are clear: As most traumatic experiences are unexpected, large-scale data gathering and follow up would be required to determine the impact. However, nonprospective longitudinal studies also bring with them a set of methodological difficulties, including attrition and baseline measurements taken after the traumatic event, when growth may already have occurred. Yet such work is crucial for the development of this field, and various dynamic modeling techniques exist that may be valuable in conducting longitudinal analyses.

A recent meta-analysis of longitudinal research on 102 independent samples found that positive change occurs after negative life events, although differentially across different measures of change. The analysis included one study specifically of growth and others of subcomponents of post-traumatic growth, such as personal strength and positive relationships— the variable that showed the most consistent positive change after a negative event. While such a meta-analysis is a valuable step forward, many studies in the meta-analysis explored change in variables not normally considered part of post-traumatic growth, such as self-esteem and autonomy. Moreover, and importantly for the purposes of this review, the studies were almost all of personal adversity; very few explored post-traumatic growth in in a work context.

More longitudinal research would also permit us to address questions about the timing of post-traumatic growth post-event, as well as its durability and possible trajectories. Although some meta-analyses have found stronger relationships between post-traumatic growth and positive mental health the longer the time since the event, other research has identified different trajectories of post-traumatic growth, such that for different individuals post-traumatic growth may increase, decrease, or remain constant over a two-year period. This work addresses important temporal issues of post-traumatic growth that deserve much more attention.

Qualitative research has enriched the study of work-related post-traumatic growth, exploring growth in a wide range of occupational groups, identifying new facets of growth, and offering insights into the construction of narratives of post-traumatic growth. Yet here there is an opportunity for longitudinal research that allows a close investigation of the mechanisms through which post-traumatic growth unfolds and the contextual factors that enable it.

Cross-cultural research. Empirical research on post-traumatic growth has been dominated by studies in Western settings, especially American. There is now, however, a growing body of work on post-traumatic growth in other cultural contexts. As this literature continues to develop, it will allow us to explore cultural assumptions inherent in it, and to consider how culture might influence individuals’ experiences of post-traumatic growth.

There are several ways in which post-traumatic growth is likely to be affected by culture. First, culture will affect whether an event disrupts core assumptions. Such assumptions, as well as what constitutes a trauma and what may be experienced as traumatic, differ from one culture to another. In Brazil, for example, a study showed that mothers of low socioeconomic status did not find the death of their babies traumatic, both because it was a relatively common event, and because they believed the child would have guaranteed happiness in the next world. These mothers might therefore not be expected to experience such high levels of distress as many other women, or to feel the same compulsion to make meaning of what has happened. The findings of this study are consistent with research that has shown those in the West tend to assume more responsibility for events in their lives, believing that they have more control over what happens to them than do those in Eastern cultures. Individuals embedded in Eastern cultures are thus more likely to respond to a traumatic event with acceptance and a sense of destiny, whereas those from the West may feel compelled to “solve the problem” through sensemaking. Culture thus affects understandings of growth and whether or how it may happen.

Cultural differences are also found in the experience and expression of emotions, and the acceptability of sharing one’s difficulties with other people. In collectivist cultures, more common in the East, expressing negative emotions is regarded as shameful and potentially disruptive to group harmony. More individualistic cultures, especially the United States and parts of Northern Europe, have a long history of seeking professional help for personal difficulties and psychological problems. Because emotion regulation and sense-making are important for post-traumatic growth, we might expect these cultural differences to make post-traumatic growth less common in Eastern cultures. This effect might be counterbalanced, however, by the greater ease with which social support can be found within collectivist communities. In sum, we have reason to believe that cultural factors will affect the possibility and process of post-traumatic growth in various ways. Bringing a cultural lens to post-traumatic growth raises more questions than it answers. But these are critically important questions, and more research is urgently needed to address them.

Other methodological considerations. Amid the debate surrounding the veridicality of post-traumatic growth have come recommendations to gather additional assessments of growth. These include the use of a multitrait-multimethod approach, or corroborating self- reported growth with assessments by friends, family, and coworkers. There are potential problems with even these careful approaches, including, for example, the likelihood that certain aspects of growth may not be enacted behaviorally (e.g., appreciation for life), or be visible to others (e.g., growth in spirituality). Still, they merit consideration. Work-related post-traumatic growth might allow the gathering of multiple sources of data from an employee and his or her immediate coworkers, as has become common in 360 evaluation initiatives. Yet, post-traumatic growth is not a performance, and many people will not want colleagues to know what they have been through. Having one’s growth appraised by others at work in these circumstances could feel highly intrusive.

New Questions

Despite the burgeoning body of research on post-traumatic growth, many questions remain unanswered. Future research offers an opportunity to examine growth after additional kinds of work- related trauma and also growth following multiple adverse events. Importantly, the study of work-related post-traumatic growth can also shed light on organizational practices and cultures that enable and constrain growth, and on collective processes of trauma and growth.

Experiences prompting post-traumatic growth at work. Considerable research exists on highly adverse events in the workplace. These include abusive supervision; sexual harassment; bullying; as well as a death, accident, shooting, or other violent acts. Organizational restructurings and redundancies can also be very difficult, individually and collectively. We wish that people did not have such experiences at work, but they do, and all too often. Although we can seek to reduce its frequency and impact, workplace adversity will not disappear. In the new world of work, it may even increase. Is there a possibility for growth after such experiences? Research on post-traumatic growth would suggest so, and yet we know very little about it. Without minimizing the destructive experience of highly adverse workplace events, research addressing this question could be of value to employees who have suffered, and those seeking to support them. A study following employees over time would also permit examination of another important and largely unaddressed issue in post-traumatic growth research, which is the common experience and impact of sequential adverse events (for example, a workplace accident, followed at a later date by a difficult restructuring initiative) on the post-traumatic growth process.

Organizational conditions enabling post-traumatic growth. Research on post-traumatic growth has tended to examine the individual processes through which post-traumatic growth emerges, and how these are enabled by the role of social support from immediate others. Considering the process of post-traumatic growth in the context of organizational life raises intriguing questions about the structures, practices, and cultural norms that support and enable the occurrence of post-traumatic growth for employees, and those that are likely to impede it. Recent research on compassion in organizations and studies of companionate cultures offer important insights in this direction but more research is needed to explore the difference that leaders, managers, and various organizational practices can make in the development of post-traumatic growth after significant workplace adversity.

Collective trauma and post-traumatic growth in organizations. Another important direction for future research is the study of trauma and post-traumatic growth as they occur among groups of individuals in an organization. To date, post-traumatic growth research has been dominated by studies of individuals’ growth following a traumatic event. Although these include events such as natural disasters or mass shootings that affect many people at a time, there is a dearth of research on post-traumatic growth as a collective process. Research on trauma and suffering in organizations highlights the important ways in which employees can affect each other’s experiences of distress and recovery. Yet we still know very little about how the process of post-traumatic growth may be affected by experiencing it alongside others who have suffered in a similar way. Such research could make a significant contribution to the post-traumatic growth literature, and to our understanding of collective healing processes in organizations more generally.

CONCLUSION

This article has sought to introduce work-related post-traumatic growth to those unfamiliar with it, provide an up-to-date review of the literature for those with an interest in it and, through Figure 1, inspire more research on post-traumatic growth as it is experienced in the context of work and organizations. This is an area rich with important implications for our understanding of individual and collective processes of growth, and the organizational conditions that facilitate and impede them. We all wish that work-related and personal trauma were on the decrease, but there is no sign of that. In this context, it is somewhat miraculous that research shows that people can not only recover from terrible adversity but potentially reap from it, showing the extraordinary strength and creativity that characterizes humanity at its best.