Reading: Two Christian Theologies of Depression: An Evaluation and Discussion of Clinical Implications

Author: Anastasia Philippa Scrutton

There are many Christian theologies of depression. Depression is spoken of variously as the result of personal or original sin, as a kind of sin (e.g., despair), as a sign of demonic possession or as involving demons, as a test of faith, as a sign of holiness, or as an occasion for spiritual transformation. Although it is difficult to draw any absolute distinctions, we might helpfully split them into the following three categories for the sake of discussion:

Spiritual illness (SI), in which depression and other forms of mental illness are believed to be a kind of SI. This includes the ideas that depression is caused by sin or demons (or both);

Spiritual health (SH), where depression is viewed as an indication of (and means to furthering) holiness or closeness to God; and

Potentially transformative (PT), where depression (along with many other instances of suffering1) is inherently bad and undesirable, but can become the occasion for the person’s spiritual growth (e.g., compassion, insight, appreciation of beauty).

Of these three, SI theology is the most famous, being so well-known that it is simply dubbed the ‘Christian belief model’ or the ‘religious explanation’ in some sociology of religion literature. SI theology is still common, particularly in some Evangelical and Charismatic communities. As someone on the receiving end of this theology describes it:

When dealing with people in the church ... some see mental illness as a weakness—a sign you don’t have enough faith. They said: ‘It’s a problem of the heart. You need to straighten things out with God.’ They make depression out to be a sin, because you don’t have the joy in your life a Christian is supposed to have.

Because of the prevalence of SI accounts in highly vocal Christian communities, such as some Evangelical communities, and because of the testimony by depression sufferers of the effect this theology has had on them, SI accounts have been well-documented by sociologists, pastoral theologians, and other academics and practitioners. However, SH and PT theologies are also worthy of attention, because these too are found among a number of Christians. Furthermore, philosophical exploration of these theologies may not only challenge existing perceptions of Christian views of depression and other forms of mental illness, but, in addition, may offer valuable therapeutic resources for psychiatric and medical practice.

Overview of This Paper

In this paper, I outline and evaluate SH and PT theologies of depression. I argue that, within the context of Christian theology, SH theology has valuable properties but also some severe problems, whereas PT theology maintains the most valuable properties of SH theology without sharing its pitfalls.

The discussion is relevant to debates about the relationship between mystical and pathological experiences of mental distress—a debate that has important clinical implications about the treatment of service users who interpret their experiences in religious terms. In the second part of the paper, I examine some of these clinical implications in critical dialogue with Simon Dein and Gloria Durà-Vilà’s 2009 article, ‘The Dark Night of the Soul: Spiritual Distress and Psychiatric Implications,’ applying the conclusions of the first part of the paper to argue that distinguishing between pathological and salutary depression is mistaken and dangerous. Although the primary focus of my discussion is depression, there is a related debate about the pathological status of some religiously experienced forms of psychosis (hearing voices, seeing visions/hallucinations), and at times ref- erence are made to these experiences and that debate. In my concluding remarks, I reflect on the broader theological and philosophical context of the PT theology I have advocated.

I am approaching this question as a philosopher of religion, and have an interest not only in describing different Christian theologies of depression (although I am interested in this), but also in evaluating them using philosophical and theological criteria. As a result, the article will be relevant to two quite distinct groups of people:

- People approaching questions to do with religion and psychiatry from an etic perspective (i.e., as an out- sider to the Christian tradition), who wish to know what different Christians believe about depression, and, perhaps, whether these are therapeutically help- ful or unhelpful religious beliefs for the Christians to hold. This group includes mental health professionals who are interested in the religious beliefs of service users, and in the implications of religious belief for clinical care.

- People approaching these questions for an emic perspective (i.e., from inside the Christian tradi- tion, or from a tradition or form of spirituality that shares some of the same ideas), who are interested in the possibilities for making sense of depression in religious/spiritual terms, and in which of these theologies is to be preferred (and why). This group includes theistic philosophers, theologians, and reli- gious believers who are interested in what it makes most sense for them, themselves, to believe.

The fact that the people in group 1 are approaching the question from an etic (outsider) perspective does not entail that they are in fact non-Christian or non-religious; they may simply have put their own religious commitments to one side in their role as mental health professional in the interests of professionalism. For this reason, it is possible for one person to be both a 1 and a 2 reader (e.g., to adopt an etic perspective in their role as a psychiatrist, but an emic perspective when approaching the question as a practicing Christian).

People who are approaching the question solely from 1 may find that some of the things I say come across as prescriptive—for instance, because I argue that one theology is to be preferred over the others, rather than simply describing the theologies in turn. That is because theology and philosophy are often more explicitly evaluative disciplines than, say, sociology or anthropology. However, against the charge of being overly prescriptive, it should be borne in mind that I am not intending to convert non-Christians (or non-religious people) to a theological viewpoint. Moreover, I am not attempting to address the complex question of whether a mental health professional should dissuade a religious service user against (what I regard as) an unsound and damaging theology (e.g., an SI theology) in favor of a more philosophically and therapeutically promising one (as I argue, a PT one). Therefore, the paper is not written with the intention of convincing mental health professionals to persuade service users of a particular theology if that theology is not something the service users believe already—that is a thorny ethical question that requires separate consideration.

Criteria for Evaluation

On what basis should religious beliefs about depression be evaluated? I use several criteria. The first relates to the therapeutic value of a belief.Therapeutic can mean that the belief promotes the cure of the sufferer from mental illness, but it can also carry a more general sense of promoting the kind of healing that may take place even in the absence of a cure, which involves the person finding meaning and value in their lives, even while their suffering is ongoing. Including ‘therapeutic’ as a criterion presupposes that health and happiness are good and desirable goals, and this is based on a prior commitment to the idea that suffering is (in philosophical terms) an evil (i.e., undesirable and negative) state of affairs we should attempt to lessen or eliminate where pos- sible (unless the suffering is a means to a good end—as in, for example, the case of childbirth).

A second criterion relates to whether the belief is realistic or true to experience. In other words, is the belief plausible, given what we know about the experiences of depression from people who have suffered it? Among other things, this involves a concern not to romanticize suffering—that is, not to impose an idealized view of the experience of suffering. The romanticization of extreme suf- fering takes place from outside the experience of extreme suffering2 and, therefore, cannot be considered realistic or true to experience.

A third criterion has to do with the logic of particular arguments. For example, are the factors cited as an argument for a particular position most simply and intuitively interpreted as supporting that position, or does another explanation appear more likely?

Although these criteria and concerns are open to debate, none of them is particularly original or controversial and it seems unnecessary to preempt possible objections to them; I therefore leave justification of them to future discussions, if necessary, in the light of responses to this paper.

What Is SH Theology?

Although many Christians portray mental illness as a form of SI, others see selected cases of (what is called by others) mental illness as a form of SH—as something that indicates, and furthers, holiness and closeness to God. In the context of depression, this is found particularly in some Catholic thought, drawing on the tradition of the Dark Night of the Soul. In this narrative, a period of spiritual dryness and sense of abandonment by God is not a permanent devastation but part of the journey toward union with God. Therefore, feelings of depression and abandonment by God, perceived diachronically, become a time of crisis that gives rise to an opportunity for spiritual transformation, and (what superficially appears to be) ‘mental illness’ is viewed as ultimately instrumental of salvation. This contrasts with a SI theology, because the sufferer is judged positively rather than negatively (their suffering is the result of their closeness to God rather than their sin, and so as a sign of SH rather than SI). However, ultimately there are also crossovers between the two theologies: for example, that suffering is pedagogical often includes an emphasis on chastisement and/or purgation which is common to both.

According to SH theology, the spiritual experience of mental distress (of, say, a saint or other spiritual person) is fundamentally distinct from mental illness, even though they share some of the same manifestations (such as periods of depression, hearing voices, and having visions). Therefore, according to SH theology, one can distinguish between pathological and spiritual (or ‘salutary’) kinds of depression and psychosis—the former is mental illness, and the latter is not.

Like SI accounts, SH theology posits a supernatural etiology: in SI theology, the experience is a punishment by God for sin, or the ‘natural’ result of sin, or the result of demonic activity; in SH theology, God is thought to cause the experience precisely to show the person’s holiness, bring them closer to God, and/or improve them in some way. However, whereas SI theology sees mental distress as supernatural and negative (caused by demons, or sin, or God [but as the result of sin]), SH theology sees instances of mental distress as supernatural and positive (caused by God, directed at the person’s salvation, and as a sign of their closeness to God). These distinctions are often matters of emphasis rather than absolute differences (something may be both the result of sin and directed at the person’s salvation), yet there is a real distinction between the two theologies in terms of the way they view the person’s spiritual status: on SI theology, the depression sufferer is especially far from God, or spiritually ill; on SH theology, the depression sufferer is especially close to God, or spiritually healthy in comparison with other people. Proponents of SH theology often identify depression and other instances of what other people see as mental illness with the experiences of some of the mystics, and emphasize the idea of purgative (i.e., cleansing) suffering intended to purify and strengthen the person’s love for God.

Examples of SH theology are found in responses to the revelation of Mother Teresa of Calcutta’s ongoing experience of acute mental distress. Letters to her spiritual advisors, published posthumously, reveal that Mother Teresa experienced an intensely painful feeling of God’s absence, which began at almost exactly the time she began her ministry in Calcutta and, except for a 5-week break in 1959, never abated. In her own words:

Now Father—since 49 or 50 this terrible sense of loss—this untold darkness—this loneliness this con- tinual longing for God—which gives me that pain deep down in my heart—Darkness is such that I really do not see—neither with my mind nor with my reason—the place of God in my soul is blank—There is no God in me—when the pain of longing is so great—I just long & long for God—and then it is that I feel—He does not want me—He is not there - ... God does not want me—Sometimes—I just hear my own heart cry out— “My God” and nothing else comes—The torture and pain I can’t explain.

Of the discrepancy between her inner state and her public, famously joyful demeanor, she wrote that her smile is a ‘mask’ or a ‘cloak’ that ‘covers everything’.

Mother Teresa asked for the letters to be destroyed, but her wish was overruled by the Catholic Church. The Reverend Brian Kolodiejchuk, who compiled and edited her letters for publication, interprets Mother Teresa’s letters in an SH way, describing her experiences as a sign of the ‘spiritual wealth’ of her interior life, and published the letters as proof of the faith-filled perseverance that he regards as her most spiritually heroic act. Similarly, the Reverend Matthew Lamb interprets the published letters as an autobiography of spiritual ascent, to be ranked alongside Augustine’s Confessions and Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain. One of her spiritual advisors, Archbishop Perier, advised Mother Teresa that her agony was a grace granted by God and a purification and protection against pride after the success of her work. For these men, Mother Teresa’s ongoing mental distress is regarded as being caused by God as an indication of her close relationship with God, and as something that increased her holiness and/ or spiritual heroism. Through the spiritual direction of Perier and others, Mother Teresa began to see her experiences in terms of something that would both ‘please Jesus’ and bring others to him. The emphasis on purification and protection against pride highlights both the similarity and difference between an SH theology and a SI one. They are similar in that the suffering has a chastising function in cleansing the person from sin and so is, in some sense, the result of sin (the person would not need to suffer if no element of sin remained in them). They are different in that, for SH theology, the chastisement for sin is an indication of their extraordinary spiritual status (their holiness and closeness to God) rather than the reverse—the result of their sin or a sign that they have not been saved.

Evaluation of SH Theology

An advantage of SH theology is that it can help sufferers to make sense of their experiences, and to find aspects of them transforming. In so doing, it brings meaning and value to experiences in a way that purely biomedical approaches cannot, including experiences of mental distress in which there is little chance of recovery. For example, someone who experiences their depression as a dark night of the soul—an indication of their closeness to God that will eventually bring them closer still—is likely to have a greater sense of the meaning of their experience, which may in turn be a source of healing and therapy, than someone who believes their condition is purely a chemical imbalance. A person with psychosis who believes her experi- ences are part of her divine mission, provided that her belief-influenced experiences bring her peace and joy rather than fear and anxiety, may find her psychotic experiences transformed into positive religious events rather than episodes marked by fear or uncertainty. Notably, the meaning-giving aspect of religious interpretations of depression is shared by SI and PT accounts as well, although in the case of SI accounts the belief is more likely to imbue the experience with fear, anxiety and/or guilt than with peace and joy.

This meaning-giving dimension is deeply rooted in SH theology and, because the meaning tends to be positive and brings a sense of peace and/or joy, seems to be a therapeutically valuable feature of it. However, a risk with SH theology is that the suffering involved in mental illness is idealized or romanticized. As Dan Hanson, whose son J(oel) has been diagnosed with schizophrenia and believes himself to have been Jesus in his past life, puts it:

People tell us that in another time and place J could have been a shaman or prophet. I am sure they are trying to make us feel better. But there are times when I resent their comments. What do these people know of mental illness, I ask myself. Have they lain awake all night wondering if their child will hurt himself or someone else?... Have they watched their child sit out in the snow for hours wearing only a light jacket, his arms stretched out to the heavens crying for aliens to come and rescue him from a hard, cold world that doesn’t recognize or appreciate him?... Have they helped lock up someone they love in a psychiatric ward? Have they had their hopes dashed by a system that is not equipped to deal with... their ill child? How dare these people trivialize what we got through by simply stating ‘he could have been a shaman’ as if conjuring up some spiritual role makes it all better.

As Hanson’s response highlights, an SH interpretation can romanticize (and so blithely ignore the reality of) the suffering that goes on in the lives of people with mental illness and those who care for them. In so doing, it represents something that is in fact an evil (human suffering) as a quasi-good, and as not an evil at all. Furthermore, in associating psychological distress with closeness to God or being somehow spiritually elite (in Joel’s case, as shamanism, and, in Mother Teresa’s case, as indicating her closeness to God), this view may also hinder recovery by diminishing the person’s motivation to recover. It may cause them to wish to remain ill, so that they can remain spiritually special. This is significant in relation to the thera- peutic value of the belief, since not wishing to be cured (at some level) can be an obstacle in the recovery process.

In addition, in viewing depression, hearing voices, and having visions as either pathological or spiritual experiences, SH theology tends to overlook accounts that testify to the complementarity of medical and psychological treatments, on the one hand, and the spiritual and transformative elements of the experience, on the other. It therefore does not pay due attention to the lived reality of depression for many people. It is also dangerous in discouraging some religious people from taking ‘psychiatric’ medications that might help their condition, while, equally dangerously, dismissing the experiences of other sufferers as not religiously valuable.

Is it possible to hold on to the meaning-giving dimension of SH theology while jettisoning these negative characteristics? Here, I argue, we need to turn to PT theology.

What Is PT Theology?

PT theology is the idea that depression is both inherently negative, and also PT (in terms of developing insight, compassion, appreciation of beauty, and other aspects of spiritual and psychological maturity). It can include (although it is not limited) to the idea of the ‘wounded healer’—the idea that the wounded person has unique healing capabilities and/or even that woundedness provides characteristics necessary for the healing of others (“only the wounded physician heals”). It is expressed by priest and psychologist Henri Nouwen who, looking back on the journal he kept during his depressive breakdown, wrote:

It certainly was a time of purification for me. My heart, ever questioning my goodness, value, and worth, has become anchored in a deeper love and thus less dependent on the praise and blame of those around me. It also has grown into a greater ability to give love without always expecting love in return.... What once seemed such a curse has become a blessing. All the agony that threatened to destroy my life now seems like the fertile ground for greater trust, stronger hope, and deeper love.

[...]

A very different example of a PT theology of depression was suggested to, and later adopted by, the Quaker writer and activist Parker Palmer. In his autobiography, Palmer relates being offered images by his therapist that became the guiding interpretation of his experience of depression and which Palmer says ‘helped me eventually reclaim my life’:

‘You seem to look upon depression as the hand of an enemy trying to crush you,’ [my therapist] said. ‘Do you think you could see it instead as the hand of a friend, pressing you down to ground on which it is safe to stand?’

When Palmer first heard these words they struck him as ‘impossibly romantic, even insulting.’ However, he also writes that, in the moment of scoffing at them he also felt that ‘something in me knew, ... knew that down... was the direction of wholeness.’ In particular, he felt that his suffering had started prior to his depression because he had been living an ungrounded life, ‘at an altitude that was inherently unsafe’:

The problem with living at high altitude is simple: when we slip, as we always do, we have a long, long way to fall, and the landing may well kill us. The grace of being pressed down to the ground is also simple: when we slip and fall, it is usually not fatal, and we can get back up.

Palmer puts living at high altitude down to operating out of his head rather than his whole body, inflating his ego to ward off fears, embracing an ethic of ‘oughts’ rather than of genuine humanity, and accepting abstractions rather than seeking experience of God. He explains that he initially saw depression as an enemy because he had ignored the more sociable efforts of his interior life to get his attention. In fact, his interior life was not an enemy but a friend who, becoming increasingly frustrated, struck him with depression to get him to turn and ask simple questions about what he wanted. Once he had taken that difficult step, he began to get well. Nouwen compares his depression with ‘fertile ground,’ and Palmer compares it to a ‘friend’—what is common to both is that (over time) both sufferers saw their depression as an occasion to grow or to become in some way better (mentally and spiritually) than they had previously been.

Differences Between SH and PT Theology

PT theology is like SH theology in some respects, but they are also importantly different.

They are similar in that, in contrast with biomedical approaches to depression, they are both meaning-giving rather than problem-solving theologies, and, in contrast with SI theologies, they give a positive rather than a negative meaning to experiences of depression. For these reasons, they both have therapeutic value.

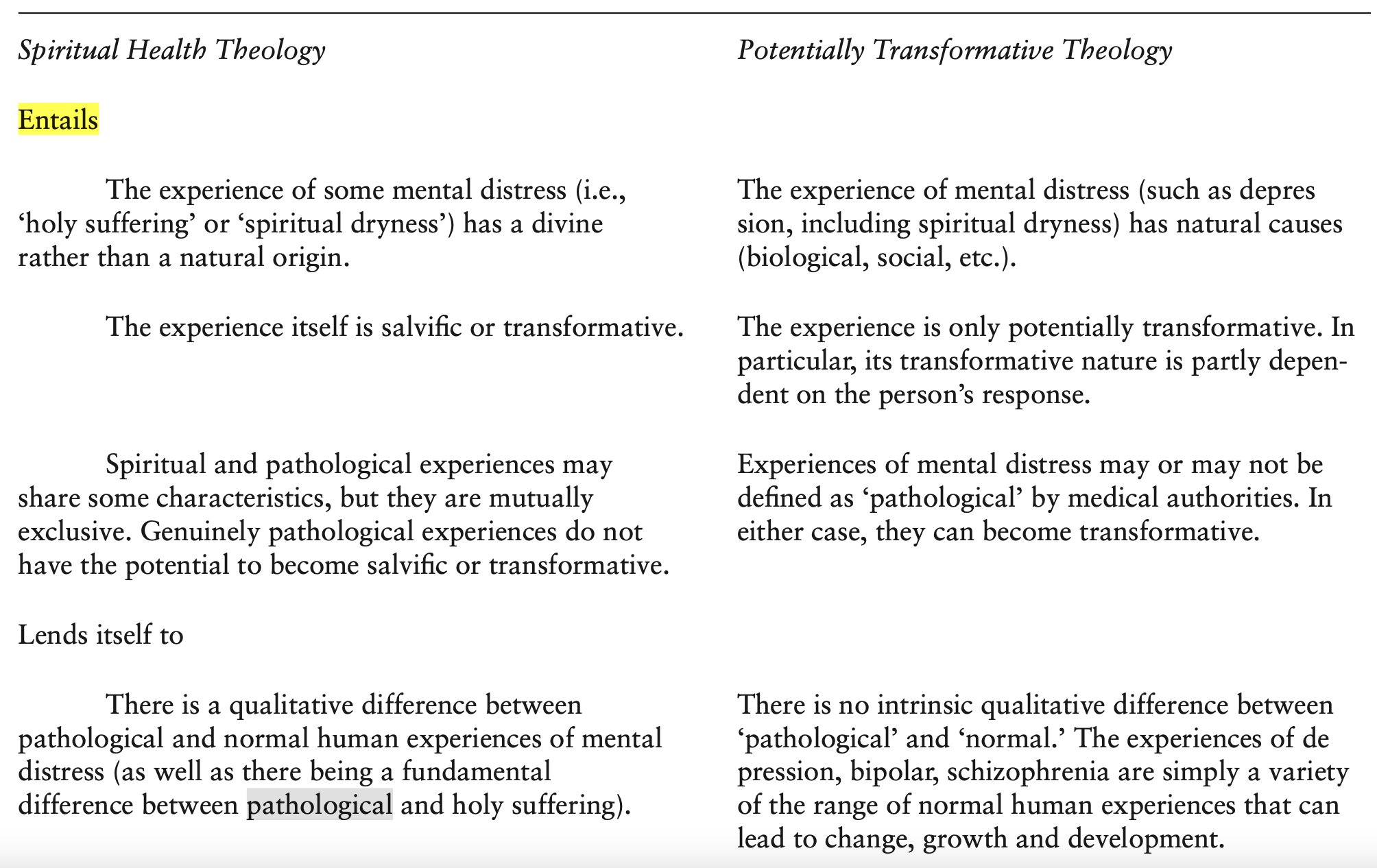

PT theology is different from SH and SI theology in that it does not put forward a supernatural etiology: the causes of depression are natural. Relatedly, less emphasis is put on the redemp- tive power of the suffering itself, and more on its redemptive potential—particularly the potential inherent in the person’s response to it (Table 1). Consequently, suffering itself can be seen as undesirable and negative. Unlike SH theology, it is not the case that suffering is idealized.

An aspect of the fact that transformation relies heavily on the person’s response is that the experience is more likely to be or to become transformative if the person believes it is or may be transformative—that is, if they themselves (implicitly or explicitly) adopt or are open to a PT theology. This characteristic is particularly relevant to clinical contexts, because dismissing a religious person’s transformative view of their experience may encourage them to discard it in favor of a non–meaning-giving and purely biomedical model, and so reject a potential source of therapy. To downgrade a PT account of depression in a clinical context on the basis of its religious origin and content is to do the depression sufferer a grave disservice, for it is to deprive them of a potentially therapeutic interpretation of their experience.

A related distinction between PT and SH theologies is that a PT theology presupposes that there is no difference in either origin or potential between mental distress that is spiritual and transformative, and mental distress that is pathological. Rather, as Anton Boisen argued, the distinguishing feature of these states “is not the presence or absence of the abnormal and erroneous, but the direction of change which may be taking place”. According to PT (in contrast with SH) theology, all mental distress is alike in origin (having a variety of ‘natural’ causes) and in potential (the realization of which is partly dependent on the person’s response). A particular case of mental distress may be defined as pathological by a medical (or religious) authority, but whether it is or not does not determine whether it becomes transformative. This makes PT theology more plausible than SH theology, because it recognizes that there are often no clear-cut and impassable boundaries between pathological experience and what may be or become conducive to spiritual growth.

PT Theology: The Causes of Depression

Among instances of PT theology, there is a general acceptance of ‘natural’ explanations for psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia, but no consensus about what their natural causes are. They may be biological or else social/environmental, or a combination of both. Some forms of PT theology do express the idea that mental illness—usually depression rather than schizophrenia—is a symptom of deep-rooted psychological or spiritual dissatisfaction or unfulfillment. For example, Lee Stringer, who spent 12 years as a homeless drug-addict in New York city, suggests this when he writes:

We, all of us, suffer some from the limits of living within the flesh. Our walk through this world is never entirely without that pain. It lurks in the still, quiet hours which we, in our constant busyness, steadfastly avoid. And it has occurred to me since that perhaps what we call depression isn’t really a disorder at all but, like physical pain, an alarm of sorts, alerting us that something is undoubtedly wrong; that perhaps it is time to stop, take time-out, take as long as it takes, and attend to the unaddressed business of filling our souls.

Notably, the idea that depression is an ‘alarm,’ alerting us to the need to ‘fill our souls,’ does not preclude the idea that the condition also has (at least partly) a physiological cause and/or cor- relate. Nor does it suggest that taking physical treatments is necessarily a bad idea, because these may allow the person to function on a day-to-day basis—which, in some instances, may arguably be a prerequisite for transformation. What it does indicate is that, at least in some cases, regarding these physical treatments as a cure that gets rid of the entirety of the problem is not the wisest way to approach the situation, just as it would be mistaken to think that taking ibuprofen to get rid of a headache is sufficient, if and when the headache is in fact the symptom of a more deep- rooted problem.

Like SH theology, PT theology forms a corrective to the biomedical approaches to depression that see the condition purely as a problem to be solved, and so eschew the meaning that can be found in it. However, it is also preferable to SH theology in several respects. It maintains that depression is inherently bad (in the sense of undesirable), and refuses to idealize the suffering that accompanies it. It creates a middle ground that holds together the desire for a cure with the insight that the condition adds value or meaning to the person’s life or allows them to grow in some way.

Three Objections to PT Accounts

One objection that faces PT accounts is that it is possible that the retrospective nature of the accounts reduces their validity. In other words, it raises the question, do PT accounts reflect a romantic take on the experience of depression after the event? I think that this is not necessarily the case, because some writers speak of present, and even permanent, depression as transformative. For example, David Karp talks about how his realization that his depression is almost certainly permanent has caused him to move beyond a simply problem-solving approach to mental illness to a transformative and spiritual one:

The recognition that the pain of depression is unlikely to disappear has provoked a redefinition of its meaning, a reordering of its place in my life. It has taken me more than two decades to abandon the medical language of cure in favour of a more spiritual vocabulary of transformation.

Again, David Waldorf, an artist and long-term resident at Creedmoor State Hospital in New York whose diagnoses have included schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorder, says he would probably prefer to continue experiencing his condition rather than to forfeit the insights he has gained from it:

I think if an angel came up to me and said, “David, you can be healed of mental illness, but you’ll never again know the worth of life again like you did when you were ill,” I think I’d have to pick the mental illness. ‘Cause that’s just how I feel, that it does show me a beautiful, enchanting side of life that I never saw before.

Karp’s and Waldorf’s claims are significant because their conditions are ongoing and probably permanent: they are not the result of nostalgia about past suffering.

I have already noted that the belief that a trans- formative experience of depression is more likely to occur in people who have a belief in (or at least openness to) the idea that their negative experience can be transformative. This raises a second objection: do people like Karp and Waldorf actually have a prior commitment to a transformative model that biases their assessment or gives them an agenda for falsely evaluating their experiences as they do? I think it would be difficult definitively to disprove this, but my sense is that there are sufficient people who genuinely do experience the condition as transformative and who are simply ‘open’ to this possibility in advance (rather than having a strong commitment to the belief) to make this unlikely.

A third objection to a PT theology is that autobiographical accounts such as Nouwen’s and Palmer’s may unconsciously produce a kind of spiritual elitism that may alienate people who experience their depression purely negatively rather than as an opportunity for growth. In other words, Nouwen and Palmer’s accounts are (according to this objection) tantamount to saying ‘I have accomplished all of this during my experience of depression—so should you.’ This is a very serious objection for, if true, it would mean that a PT theology would not empower and edify the person who suffers from depression, but, rather, contribute further to their experience of debilitation and loneliness. In short, if true, it renders PT theology destructive rather than therapeutic.

I think this is a genuine risk for the way in which a PT theology is often used, but I do not think it is essential to it. In the examples we have been considering, because Nouwen and Palmer speak only of their own experiences, they do not prescribe what others ought to experience. In recounting their own experiences, they suggest a hopeful possibility to others, without indicating that what they experienced is or ought to be or can be universal. To say that recounting their own experiences as transformative amounts to saying that that of others ought also to be is analogous to saying that the Life of Pi suggests that anyone stranded on a boat with a tiger ought to be able to survive. This is not the case because (as the respective authors are likely to recognize) people differ greatly—as do the boats in and tigers with which they find themselves. This objection does raise an important caveat for pastoral contexts, though: although it may be helpful to some to speak of one’s own experiences (as Nouwen and Palmer do), to preach to another about the transformative poten- tial of their depression (or other form of suffering) is likely to be glib, insensitive, and even damaging (see Scrutton 2015). Notably, it is the preaching here that is problematic rather than a PT theology itself—and this is not particular to PT theology.

Summary

So far, I have outlined SH and PT theologies of depression. I have argued that both have an advantage over a purely biomedical model in encouraging people to find meaning in their experiences, and over SI theology in promoting positive rather than negative meanings, and so have greater therapeutic value than these alternatives. I have argued that PT accounts are preferable to SH ones because they resist the temptation to turn depression into a good in disguise, and so do not idealize or romanticize the suffering involved in mental illness, or dissuade the sufferer from seek- ing recovery from their condition. Relatedly, I have indicated that they are true to people’s experiences. Finally, I have responded to three criticisms of PT theology, introducing a pastoral caveat as a response to the third.

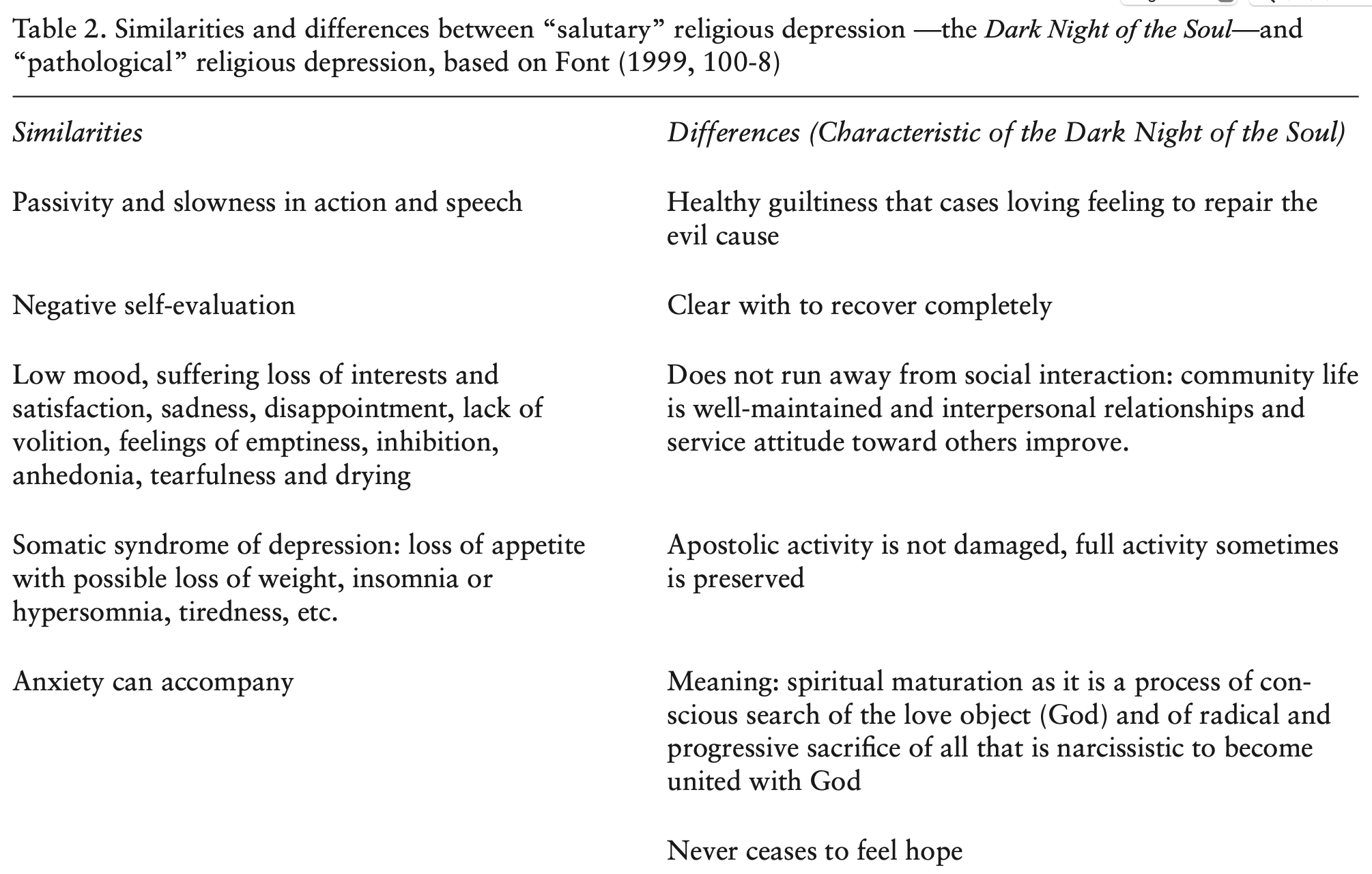

Implications for Clinical Practice: A Critical Dialogue with Durà-Vilà and Dein

In an important 2009 article, two psychiatrists, Gloria Durà-Vilà and Simon Dein, make the valuable point that the attribution of meaning to the experience of psychological suffering is a crucial (therapeutic) element, and that psychiatrists may hold up or even prevent the attribution of meaning to take place for instance, by enforcing a purely biomedical interpretation. Less helpfully in my view, they develop a distinction between salutary religious depression and pathological depression. The two have different symptoms (Table 2). The clinical implications of their view are that while pathological depression is the domain of psychiatry, salutary depression can be “a healthy expression of spiritual growth” and lies outside the domain of psychiatry. This seems to be a psychiatric form of an SH theology, in which the experience of depression is intrinsically religious and quite separate from pathological experience.

Is Durà-Vilà and Dein’s argument persuasive? Their conclusion seems questionable to me, be- cause the symptoms of salutary depression as distinct from pathological depression (e.g., not ceasing to feel hope, and full or partial preserva- tion of ‘apostolic’ activity) are more likely to be the consequences of adopting a positive meaning- giving (SH or PT) account, and do not require us to posit a more fundamental qualitative difference between kinds of mental suffering.

Their view may also be counterproductive. One reason for this is that distinguishing between two forms of depression risks limiting the potential of depression diagnosed as ‘pathological’ to become transformative and therefore ‘salutary.’ This is particularly a risk among people who do not have the Catholic Christian theological structure, which would allow them to identify, and to have their condition identified as, a Dark Night of the Soulexperience. PT theology addresses this problem by entailing that all depression and mental distress has the potential to be salutary—that is, to have meaning and be transformative—and does not exclude sufferers who do not recognize or conform to the Dark Night paradigm.

Moreover, Durà-Vilà and Dein conclude that it would be meaningless to consider the emotional distress of people with salutary depression as a dis- ease, and that “telling them that their experience of the Dark Night is abnormal or pathological and offering a chemical disturbance in the brain as an etiological factor—so antidepressant medicine may be taken—may deprive these religious people of the opportunity to give meaning to their experience”. Durà-Vilà and Dein are importantly right insofar as prescribing antide- pressants as a panacea, and neglecting the spiritual and/or psychological dimensions of depression, is a dangerous tendency in medical treatment. But this seems to be true for all or at least most depression, whether or not it is religious in character. In implying that there is not a biological component in the depression of Dark Night soul sufferers,4 and that antidepressant drugs should not be given to certain religious people who interpret their experiences in transformative (or Dark Night), terms, Durà- Vilà and Dein’s approach may prove dangerous in discouraging doctors from giving antidepressant drugs to religious people who need them to get through each day. They also overlook the many concrete examples of people who attest to the compatibility of psychotropic drugs and spiritual/ psychological growth. PT theology, in contrast, allows for the complementarity of seeing depression both as a negative experience calling for biological and/or psychological treatment, and as an opportunity for spiritual and psychological development, at one and the same time.

Durà-Vilà and Dein’s paper also highlights the ways in which exemplars of the SH model (such as Mother Teresa, Therese of Lisieux, Paul of the Cross, and others) remained silent about their suffering, seeming cheerful to others. This fits with a wider perception of traditional Catholic views of suffering; for example, Sharon O’Brien, a professor of American cultures in Pennsylvania, articulates a similar view in the context of her perception and experience of Irish Catholicism:

[T]he religious and cultural ethic of Irish Catholicism stresses silent suffering. “Offer it up,” people used to say about some tragedy or setback, which might, if endured well, grant you “a higher place in Heaven,” as if the hereafter were organized by the reverse of earthly values. If you’re Irish, suffering is supposed to make you a better person: you’re supposed to endure it, not seek help to deal with it.

The problem with encouraging people to suffer silently is that it may increase their sense of alienation, while expressing suffering (in prudently sympathetic contexts) can bring relief and healing. Although silent suffering is not an essential element of SH theology, in seeing suffering as a form of spiritual heroism it certainly errs toward it, as O’Brien’s characterization of Irish Catholicism highlights (regardless of how accurate a description it is of Irish Catholicism).

Objections to my Argument

Two possible objections to my criticism of Dein and Durà-Vilà’s position ought to be addressed here. First, it could be pointed out that evidence suggests that, in most cases, anti-depressants work primarily as placebos. It is outside the scope of this paper to assess whether this claim is true, but let us suppose that it is in order to consider this objection to my argument. The idea that the effectiveness of antidepressants is largely placebo based is relevant to the clinical debate because someone holding Dein and Durà-Vilà’s position may respond to my argument by saying that there is no point prescribing antidepressants for religious sufferers, because they would not be effective in their cases (because they would not have a biomedical understanding of their condition, and so the placebo effect of the antidepressants would be nullified). However, this argument only holds if the person unequivocally does not have a biomedical account of their condition. Many religious and spiritual people have a (wholly or partially) biomedical account of their condition and also a transformative understanding of it, with the first being concerned with the desire for a cure, and the second with a search for meaning. Although it may be problematic to force someone (religious or otherwise) to take antidepressants, to withhold antidepressants from them or dissuade them from taking them may deprive them of a potential source of relief and so with the opportunity to reflect on their experience—something it is not always possible to do in the midst of despair. Therefore, the idea that the effectiveness of antidepressants is primarily owing to a placebo effect does not affect my argument.

A proponent of Durà-Vilà and Dein’s view might also object that curing a religious person from salutary depression would rob them of the opportunity for spiritual growth. To this, I would respond that the person would already have experienced mental distress through their depression, and that the memory of this will remain with them and that this is likely to be sufficient for their spiritual growth (e.g., a heightened appreciation of joy in God’s presence because of the memory of the feeling of divine absence; greater compassion for others who are mentally distressed). Indeed, although Karp and Waldorf attest to the possibility of transformation in the context of permanent depression, some people may be in an even better situation to grow spiritually once the depression has passed; it is notable that the Dark Night St John writes about was never intended to be a permanent condition, but a temporary part of a much longer spiritual journey.

Conclusion: Summary and Concluding Remarks

I have outlined and evaluated SH and PT theologies of mental depression and argued in favor of PT theology. A PT account, I have argued, can allow people to hold the desire for a cure and the search for meaning in balance, and gives hope, ideally that the suffering will abate, but also that life can be meaningful even if it does not.

There are several clinical implications of this view. In common with Durà-Vilà and Dein, I think that certain religious and spiritual approaches have valuable resources for psychiatric practice, in terms of their ability to add meaning and the challenge they pose to purely biomedical models. Against their view, I think that we should not distinguish between pathological, and spiritual/ transformative/salutary, experience, and that psychiatric treatments and spiritual and religious forms of meaning-giving, are compatible.

By way of concluding remarks, I would like to respond briefly to three thought-provoking ques- tions I am often asked in connection to this topic: (i) whether a PT theology also applies to other forms of mental illness, (ii) whether a PT theology also applies to physical as well as mental illness, and (iii) whether (in a theistic context) the potential for growth in suffering justifies the existence of suffering (as suggested by soul-making theodicies).

First, does a PT theology also apply to other forms of mental illness? I would not want to apply a PT theology of depression unilaterally to all forms of mental illness, partly because mental illness is a constructed category rather than a natural kind, and there are significant dissimilarities between depression and other forms of mental illness. Depression is a very different phenomenon from Alzheimer’s disease or substance abuse or paraphilia. That said, autobiographical accounts by Carl Jung, Anton Boisen, and others may indicate that a PT theology might be applicable to some instances of psychosis, and I would not want to exclude it from other forms of mental illness. What PT theology would look like in the context of psychosis or another form of mental illness would require a separate treatment to this discussion of depression.

Second, does a PT theology apply to physical, as well as mental, illness? This question highlights important questions about the concept of ‘mental illness’—for example, about medicalizing experiences such as depression (by describing them as ‘illnesses’), and about the underlying dualism implied by the distinction between ‘mental’ and ‘physical.’ Because I have some misgivings about the term ‘mental illness’ (while also recognizing it to be useful in other respects and contexts), I do not think asking whether what is true of mental illness is also true of physical illness is the most helpful question. Rather, it is more helpful to ask whether what I have said about depression applies to other forms of suffering. The answer here is yes, to some forms of suffering, mutatis mutandis. People might be transformed by experiencing poverty in a way that means they develop compassion for others, or through a period of imprisonment that gives them time to reflect on their actions, or by a spell of illness that brings them face-to-face with the fact of their eventual mortality and highlights what is important to them. The ways in which these experiences can be transformative is likely to be different in each case. What is perhaps particularly interesting about the case of depression is that some of the writers we have discussed (e.g., Stringer, Palmer) speak of depression (or at least of their own depression) as being essentially teleological—as arising for the purpose of drawing attention to and rooting out undesirable or immature spiritual or mental characteristics (unfulfilment, being ungrounded, having an inflated ego).

This leads us naturally on to the third question about whether a PT theology can go beyond saying that suffering is PT to providing an etiology of suffering in a theistic context—that is, to saying that God allows or even causes suffering (such as that experienced in severe depression) to enable us to grow morally and spiritually (often referred to as a soul-making theodicy). The answer to this is that although a PT theology is compatible with a soul-making theodicy, it does not entail one. It is possible to hold that depression can be transformative and this is why God allows or causes depression. It is equally possible to reject the idea that the transformative potential explains why God would allow evil (perhaps because one finds the task of justifying extreme suffering morally or theologically repugnant) while holding that suffering can still be transformative. Here, the theist would move away from explaining the existence of evil to an emphasis on the ability and willingness of God to bring good out of evil.