Reading: The Meta-Narratives of Philosophy - Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.

The Meta-Narratives of Philosophy

In recent decades scholars have increasingly recognized how important story is to human life and that at a very deep level human beings live out their lives in the context of a basic, foundational story. The technical word for this is metanarrative; a metanarrative is a grand story that aims to tell the true story of the world. Individuals and societies may be unconscious of the story they indwell, but always it is some particular grand story that an individual or community is living out. There are different ways that the unity of the Bible can be articulated, but we think that it is particularly helpful to approach the Bible as a drama in six acts, a drama that really does tell the true story of the world. We identify the following six acts in the drama of Scripture:[ 7]

- God Establishes His Kingdom:

- Creation Rebellion in the Kingdom:

- Fall The King Chooses Israel:

- Redemption Initiated

- The Coming of the King:

- Redemption Accomplished Spreading the News of the King:

- The Mission of the Church The Return of the King:

Redemption Completed In this way the Bible not only tells us the true story of the world but also invites us to make the story our own. It positions us clearly in act five of the drama— the mission of the church— and invites us to become active participants in God’s journey with his creation as the drama continues to unfold and moves toward its conclusion (act six). The Bible is the deposit— like the silt that settles at the bottom of a river— of God’s journey with the people of Israel

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (p. 14). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

The Role of the Bible

The Bible is not an academic textbook but a book for Christians on the journey of life. Of course our understanding needs to be fully engaged when we read the Bible, but the Bible is not given to us first of all to analyze; rather it is God’s Word to us as whole human beings and is the primary means whereby God wants to give himself to us again and again. The Bible is primarily directed at our hearts— the center of our beings— not at our heads. Its primary mode of reception is through the open heart, allowing God through the preaching of the Word or through private meditation upon

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (p. 14). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

All worldviews originate in a grand story of one sort or another. As Ecclesiastes 3: 11 says, God has put eternity— a sense of beginning and end, a sense of being part of a larger story— in our hearts, in the very core of our beings, so that we require some larger story within which to situate, to make sense of, the smaller stories of our lives and cultures.[ 11] God intended us to find meaning in our lives through being part of a larger story that gives us purpose and direction and explains our world. It is important to note, therefore, that one who rejects the Christian story will not simply live without a grand story but will find an alternative grand story to live by.

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (p. 16). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Different Models of Philosophy

The first model is that worldview and philosophy repel each other, in the sense that an unavoidable tension exists between a scientific philosophy and an existential worldview. Both are necessary, and we should not try to resolve the tensions between them.

The second model is that worldview and philosophy flank each other and are to be kept apart lest the scientific nature of philosophy be compromised. This view stems from the desire for philosophy to be thoroughly “scientific” and thus based on reason alone. Bertrand Russell’s definition of philosophy makes this clear: “Like theology, it [philosophy] consists of speculations on matters as to which definite knowledge has, so far, been unascertainable; but like science, it appeals to human reason rather than to authority, whether that of tradition or revelation. All definite knowledge— so I should contend— belongs to science; all dogmas as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to theology.”[ 13] If all definite knowledge belongs to science because it is based on reason, then a philosophy we can trust will also need to be based on reason and thus be as scientific as possible. There is indeed a rational element to a worldview, but a worldview is far more than rational, involving faith, tradition, trust, and so on. It is easy to see that if knowledge we can trust as true must be based finally on reason, then a scientific philosophy will need to keep well away from worldview and do its best to make reason its final arbiter.

The third model is that a worldview crowns philosophy— that is, it is the crowning achievement of a philosophy to be able to articulate a unified worldview. From this perspective one simply cannot start from a unified worldview, but philosophy can slowly work toward articulating the contours of a unified view of the world. A clear example of this is found in Phil Washburn’s Philosophical Dilemmas: Building a Worldview. Washburn states that “the goal of philosophy is to build a coherent, adequate worldview.”[ 14] He defines a worldview as “a set of answers to questions about the most general features of the world and our experience of it.”[ 15] For Washburn, philosophy enables the individual to construct his or her own worldview; it is a long and challenging endeavor.

The fourth is that a worldview yields a philosophy— that is, a worldview can be developed into a philosophy. Since this is the view we espouse, we will leave elaboration of it to the end of this chapter. The fifth model is that worldview equals philosophy. How do we judge between these approaches? Intriguingly, the view you take will be determined by your worldview and your view of philosophy!

This is apparent, for example, from Washburn’s guidelines for constructing a worldview. He suggests three guidelines for such construction:[ 16] one’s worldview should be based on human experience in the widest possible sense; one should attend closely to how the different parts of one’s worldview are interconnected and ensure their compatibility; and one should only accept answers to the basic worldview wish questions that are clear and understandable. He acknowledges that “the guidelines are based on the nature of philosophy itself.”[ 17]

It would be more accurate to say that his guidelines are based on his view of the nature of philosophy. For Washburn, the individual constructs his or her own worldview, and the guidelines reveal that experience and reason are the key criteria.

This reveals a typically individualistic, modern view of philosophy based on human autonomy. If you adopt a view of the world according to which humankind— and in particular humankind’s reason— is the measure of all things, then you will clearly opt for one of the first three models, since in different ways they all assume the autonomy of philosophy. The autonomy of philosophy involves a belief that one can step outside of one’s worldview and operate in a neutral, autonomous way in search of the truth about the world.

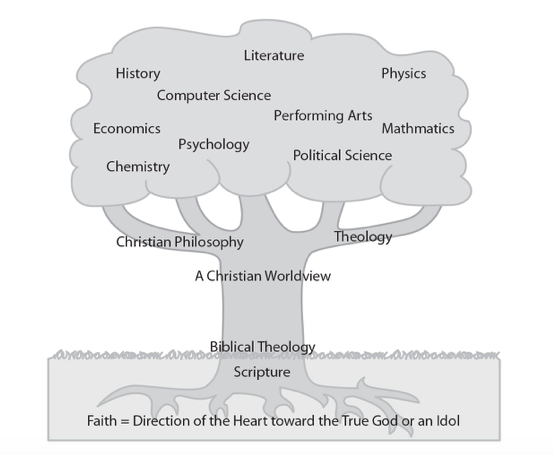

The crucial question is whether a worldview, with its religious underpinnings, can be set aside in this way. In the history of philosophy it is is deeper than either philosophy or science; indeed, philosophy and science stand on the foundation of one’s worldview. As Sander Griffioen puts it, “Philosophy itself is dependent on worldview. Dilthey attributed the metaphysical search for ultimate unity to worldviews, which in turn underlie philosophies.”[ 19] In our opinion this is correct. Not only is a worldview unavoidable but so too is some kind of religious faith underlying a worldview. But, you might object, how can this possibly be the case when so many people, and especially philosophers, are not religious? Again it all depends on what you mean by “religious.”

Clearly multitudes of secular philosophers do not attend church regularly or pray to the Father or indulge in any overtly “religious” activities. However, from a Christian perspective we know that humans are creatures— and religious creatures— by design. Because we are creaturely and not the Creator, we always depend on something as the ultimate source of meaning. We are made for God, and if we will not have him, then inevitably we find a replacement, what the Bible calls an idol.

The key to understanding how pervasive idolatry remains today is to avoid thinking of idolatry only as the worship of other gods. In his acute analysis of the nature of religion, the philosopher Roy Clouser defines a religious belief as a belief on which everything else depends but which itself does not depend on anything.[ 20] An idol can be a belief in wealth or the material world as basic reality or in human reason as the source of meaning and truth. From this perspective a Marxist is as religious as an evangelical Christian or an atheist; the difference is (only) in what they depend on as divine.

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (pp 15-20). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Al Wolters has helpfully noted that when we encounter non-Christian philosophies, we need to do two things: firstly, note the idolatry at work, but secondly, note that it is precisely at the point of idolatry that the most poignant insights will be found.[ 24] The hard task of Christian philosophy is to appropriate those insights without taking on the ideological baggage in which they are embedded. And it should be noted that we will have no chance of doing this if we have not first attended to the development of a Christian philosophy.

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (pp. 23-24). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Broadly speaking, we work in the Augustinian tradition of Abraham Kuyper and his followers.[ 25] Central to this tradition is the view that redemption involves the recovery of God’s purposes for all of creation and that no area of life, including philosophy, is neutral and exempt from religious presuppositions. In our view, it is a serious mistake to try to do philosophy on the basis of autonomous human reason. Rather, we should employ the full resources of our faith— revelation and reason— in order to develop a Christian philosophy.

Bartholomew, Craig G.; Goheen, Michael W.. Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction (p. 24). Baker Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.