Reading: Chapter 3 - TYPES OF RELIGIOUS BELIEF

Chapter 3 - TYPES OF RELIGIOUS BELIEF

Dr. Roy A. Clouser

Let us now turn to some of the major world religions of the present day and see how the definitions just developed can help us to understand them. We cannot, of course, work up a detailed comparison of even two such traditions, let alone five or six, without getting completely sidetracked from our main topic. But it will prove very enlightening if we look briefly at the most influential of the world’s religions by grouping them according to the way they view the non-divine as depending on the divine, that is, according to the dependency arrangements I referred to in the last chapter as type (2) secondary beliefs. Becoming more precise about these arrangements not only will cast significant light on these traditions, but will allow us to be more aware of such arrangements when we find them in theories later on.

3.1 THE BASIS FOR TYPING RELIGIONS

Dealing with the major world religions according to their ideas of how they see the non-divine to depend on the divine is a major benefit yielded by the definitions developed in the previous chapter. It allows us to do better than classify the various traditions according to some arbitrarily selected feature(s). In the past religions have been categorized, for example, by how many gods they had, or whether they advocated a strict morality, and so on. But these ways of typing the major traditions are not only arbitrary but too narrow in the sense that they have a very limited range of application.

Once we take the dependency arrangement idea as our guide, it becomes clear that there are three such arrangements which prevail in the world today. (These are not the only ones possible; I have been able to distinguish at least fourteen possible dependency arrangements.) I will call these three the pagan, the biblical, and the pantheistic dependency ideas. “Biblical,” as I use it, is a blanket term for the theistic belief in a transcendent Creator found in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; while the term “pantheist” includes Hinduism,

Buddhism, and the more recent forms of Taoism. The pagan type of religious belief covers such a wide variety of traditions that I cannot now clarify it by simply naming one or two of them, although we will shortly examine a few of its most influential representatives. Before doing that, however, I want to make it clear that the term “pagan” is not a derogatory term as I use it. It is not being used as, say, Christian missionaries used the term “heathen” in the nineteenth century. It does not refer only to beliefs that are superstitious or irrational, or which are held only by people deemed to be primitive. On the contrary, we will see that paganism can be quite sophisticated and that its sophisticated forms still exercise a tremendous influence in the world today.

3.2 THE PAGAN TYPE

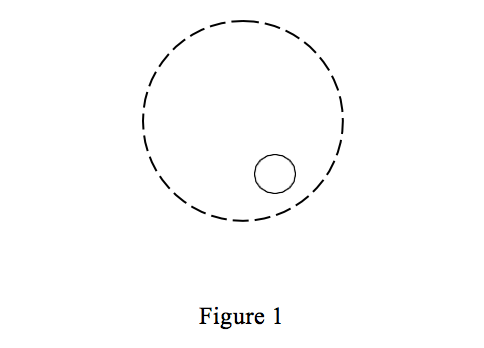

The essential feature of the pagan dependency idea is that the divine per se is some part, aspect, force, or principle in the universe open to our ordinary experience and thought. Put another way, the pagan dependency arrangement takes it that there is only one continuous reality, a part of which is the per se divine on which all the rest depends. Perhaps the following schema will help to make this clear. If we use a solid line to represent the divine and a broken line to represent the non-divine, then our visual aid for the pagan dependency idea would look like Figure 1.

A wide variety of religious beliefs fall under this pagan type. Nature religions which worshiped a divine power in the earth, the sun, rivers, the sea, etc., are all examples of it, as are most polytheisms. For example, one of the most commonly worshiped gods in the ancient world was the god that controlled storms. It was called Ba’al in the near East, Zeus in Greece, Jupiter in Rome. In each case this god was believed to be one among many divinities that are divine in the secondary sense: they were beings that owed their existence to something that is divine per se, but who had more divine power than humans do. The beliefs in Mana, Numen, and Kami as per se divinities that I mentioned earlier also fall under this type. Although these traditions often disagreed about the names and the precise descriptions of specific gods, and although some have gods others lack, they all held the divine per se to have the same general relation to what is non-divine, namely, that the divine per se is part of every non-divine thing. Thus Werner Jaeger’s characterization of this dependency arrangement when it appears in philosophy due to the influence of Hesiod, applies quite well to all pagan belief:

When Hesiod’s thought at last gives way to truly philosophical thinking, the Divine is sought within the world — not outside it as in Judeo-Christian theology that develops out of the book of Genesis.1

In connection with my remark that pagan belief is still strong in the world today, we need to keep in mind the point made in the last chapter about religion not always resulting in worship. For as long as we think only of the forms of paganism expressed in ritual and worship it will be impossible to believe that paganism is a significant force in the world today. This is because paganism that includes worship — call it “cultic” paganism — has long been in decline in the face of advances by Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as from the pressures of non-cultic pagan beliefs such as materialism and other theories that regard some aspect of the universe as non-dependent and thus as divine per se. Such non-cultic paganisms, however, have continued to flourish. Many modern thinkers in philosophy and the sciences maintain theories whose assumptions are as much pagan religious beliefs as those of their ancient counterparts. For example, while the religious commune of the Pythagoreans died out long ago, and nobody I know of worships numbers any more, the Pythagorean belief that numbers or other elements of mathematics are parts of a realm of self-existent realities on which all else depends (at least in part) is far from dead. Indeed, it continues to dominate large domains of scientific thinking to this day.2 And, as we already saw, it is equally a non-cultic pagan belief to regard matter and energy, rather than numbers, as the non-dependent reality on which all else depends. For this, too, is a case of believing some aspect of the natural world to be divine.

It might be instructive at this point to apply my account of the pagan type of religious belief to the theory of dialectical materialism proposed by Karl Marx. This is an especially interesting case since Marxism is an avowedly anti-religious theory. In its interpretation of everything from physics and biology to economics, history, and politics, Marxism professes to be opposed to all religions of whatever kind. According to Marx’s theory, matter/energy is the basic reality, and within matter there is an innate law which drives things to change according to a process he calls “dialectical” development. This law has caused matter to organize into a multitude of forms over millions of years: galaxies and solar systems, living things, humans, and human societies are all products of matter being organized by the law of dialectical development.

The Marxist hypothesis goes on to propose that this dialectical law, when correctly understood, shows that free-market (capitalistic) economics is the cause of unjust and repressive governments and is doomed to pass away. This will take place as there develop governments willing to abolish private ownership, which is the root of all evil. Once communistic economic systems can be established, they will in turn bring about governments which are ever more just, so that there will be continually greater happiness throughout all humanity. The eventual outcome will be the emergence of the final stage of history: the communist society. In such a society the citizens will not only spontaneously eschew private ownership, but never even wish for it. Because of this, crime will disappear and so will the need for government. Society will be free of the alienation of one group from another since there will no longer be classes with adversarial interests. There will no longer be any alienation from nature, or from the means of producing the necessities of life. People will be happy and good, and will live in peace.

It should be clear, however, that although Marx was indeed an atheist, his theories all presuppose the non-dependence or self-existence of matter; physical matter, along with its innate law of dialectical development, is “just there.”3 Matter depends on nothing whatever, and all of reality either is identical with or depends on matter. For this reason, despite its protests to the contrary, Marx’s theory is based on a religious belief. And, what is more to the point, this religious belief is a typically pagan one since it takes something about the universe (matter and its dialectical law) to be the self-existent segment of reality on which all else depends. We are entitled to this conclusion because our definitions have shown not only why a belief can be religious without involving worship, but why it can be religious whether or not its subscribers wish it or admit it. I mention this again because it is especially true of non-cultic paganisms that their advocates often deny their beliefs to be religious at all, and refer to them as “secular” or “nonsectarian” — terms intended to convey that they are religiously neutral. As soon as we compare these beliefs with our definition of “divinity per se,” however, we can see why many beliefs passed off as humanist or secular are in fact alternative religious beliefs.

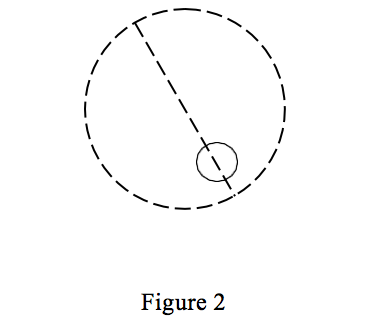

The examples of Pythagoreanism and materialism are cases of paganism in which there is only one kind of reality that is divine per se. But the most popular forms of pagan belief throughout history have belonged to a sub-type called “dualism” to indicate the belief that there are two distinct per se divinities rather than only one. According to the most influential beliefs of this sub-type, it is the interaction between the two divinities that produces the rest of reality that is non-divine. The form-matter belief of the ancient Greeks is an example of such dualism, as is the Taoist Yin-Yang doctrine. Figure 2 shows the previously offered schema altered to reflect this difference.

Usually in religions that believe there are two divine realities, one of the divinities is regarded as the source of what is good in the world while the other is the source of what is evil. The dualistic paganism of ancient Greece just mentioned is a case in point. It saw the two divinities as: (1) Matter, an original stuff of which all things are made, and (2) Form, the principle of orderliness which makes the stuff into the intelligible world we experience. Some Greek thinkers understood this divine orderliness as being logical in nature, while others saw it as essentially mathematical. Applied to the idea of human nature, this dualistic faith taught that humans, too, are combinations of form and matter. The human body is constituted of matter, which generates feeling and passion. By contrast, the human mind is an embodiment of form because it is able to reason logically and/or mathematically. On this view, all that is good, beautiful, and true has an essentially rational character and is known by the mind’s exercising rational thought. By contrast, all that is evil and disordered is brought about by the bodily impulses of irrational feeling and passion. Human life is therefore a constant struggle between one’s emotional nature and one’s rational nature, between one’s body and one’s mind.

From the basic duality of its two divinities, this version of paganism saw not only human nature but all of reality as permeated by corresponding pairs of oppositions: good vs. evil, rational vs. irrational, stability vs. change, order vs. disorder, beauty vs. ugliness, etc. This outlook still enjoys great popularity in our culture today. But no matter how comfortable many non-pagans have come to feel about it, this dualistic picture of things is in conflict with both the biblical and the pantheistic types of religious belief.

3.3 THE PANTHEISTIC TYPE

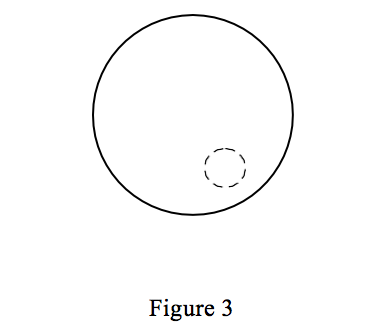

The chief examples of contemporary religions advocating the pantheistic dependency arrangement are Hinduism and Buddhism. This arrangement may best be seen as the inverse of the one held by paganism. Instead of locating the divine as a subdivision of the one continuous reality, the pantheistic belief is that whatever we experience as non-divine reality is in fact a subdivision of the divine reality, which is both infinite and all-encompassing. This last point creates an obstacle for drawing a schema to illustrate it, however, since we can’t draw an infinitely large circle. So I will simply stipulate that the finite circle in Figure 3 stands for an infinite one.

This schema shows that the pantheistic religions share with pagan religions the conviction that there is only one continuous reality. The two disagree, however, over whether there is more to reality than what is divine per se (pagan), or whether the divine is co-extensive with or greater than the non-divine, so that the latter is a subdivision of the divine (pantheistic). Given this difference, we may say that from the pagan standpoint there is a clear-cut distinction between what is divine and what is not, but from the pantheistic standpoint the distinction is a tricky issue. For if the non-divine is in its entirety part of the divine, how can there really be anything that is not divine? And if there is not, just what distinction is being drawn?

The answer given by the pantheistic traditions was already touched on in the last chapter. It says that, yes, the divine is the very essence and being of all things, but that we nevertheless experience individual things and events of our everyday world to be non-divine. So the distinction made in these traditions is not between a portion of reality that is truly divine per se and a portion that is truly not, but between the divine being of all things and the illusory appearance that there are things which are not divine. It is because the difference is so great between our illusory everyday experience (Maya) and the divine reality which lies behind it, that the scriptures and disciplines of the pantheistic traditions do not simply teach this doctrine but are aimed at inducing a mystical experience of the oneness of all things. Only by such a mystical experience, they say, can a person overcome the veil of illusion, see behind the world of mere appearance, and become aware of the divine reality which is hidden by it. This divine reality is called Brahman-Atman in Hinduism; Dharmakaya, the Void, Suchness, Nothing, Nirvana (and other terms) in Buddhism; the Tao in Taoism.

Here it should be stressed that the sense in which most of the versions of these traditions hold that the world is unreal as it is known by ordinary experience and reason is a very serious one, indeed. They do not mean only that the everyday world is less real than the divine reality it conceals; they mean that everything about it is unreal. According to them, mystical experience shows the divine not only to be the true nature of all things, but in fact to be the only reality so that the divine is all there is. Thus, even the most commonplace features of the everyday world are illusory on this view.4 For example, according to the prevailing versions of these traditions there really are no distinct, individual objects; no real differences of qualities — even including the difference between good and evil! At bottom all things are one; there is only the divine.

This doctrine usually appears strange and unpalatable to Westerners who often point out that it leads to logical contradictions. In answer to such criticisms, these traditions warn that without the necessary mystical experience people will always fail to understand or to believe in the (hidden) identity of all things with the divine. The criticism that this position is self-contradictory, they say, fails to recognize that logical thinking is also part of the world of illusion. As such, it is part of the deception that prevents people from discovering the divine unity of all reality. According to the pantheistic dependency arrangement, therefore, not only is the divine never to be conceived of as any one part or aspect of the world (as paganism does); since logic is ruled out, the divine cannot be conceived at all. This is why the Hindu and Buddhist traditions insist on a mystical experience of unity with the divine per se as the only means for discovering the truth about it.

The difference between the pagan and pantheistic dependency arrangements results in other important disagreements between them. Take, for example, the different type (3) secondary beliefs according to which they interpret human nature and the proper ordering of values in life. According to the influential Greek version of paganism sketched earlier, what is wrong with people is their failure to recognize human reason as the embodiment of the same divine principles that give order to all reality, and to work at overcoming the impulses of emotion by making rationality the highest value both in their personal lives and in human society. On this view, then, to live in accordance with reason is the proper way to relate to the divine, highest value in life, and that which leads to genuine happiness.

By contrast, the pantheistic traditions insist that what is wrong with people is that they believe the illusory world, including human rationality, to be real. Since no distinct part or feature of the natural world is either divine or even real from the pantheistic standpoint, the proper way to relate to the divine is to discover the true (divine) reality by rejecting and detaching oneself from the illusory world of ordinary experience. The highest value for humans, on this view, is not the rational ordering of life, but complete rejection of ordinary experience including reason! This, as we saw, is to be achieved through a mystical experience of complete union with the divine. Moreover, this experience does more than merely disclose the divine, it is also the means of gaining release from the (unreal) world of illusion and suffering. Thus, common to all the pantheist traditions is the teaching that the proper way to relate to the divine and the highest value in life is to seek enlightenment via mystical experience. Failure to achieve that experience in the present lifetime results in one’s being reincarnated into yet other lifetimes of illusion and suffering. And this is believed to continue (usually through millions of lifetimes) until a person is finally enlightened by mystical experience and is thereby exempted from future reincarnations. That is, once enlightened, a person is guaranteed Nirvana: the state in which one’s individual (illusory) self is absorbed into the divine “as a drop of water is absorbed into the ocean.” That is the state of “unspeakable bliss”, and thus the fulfillment of true human nature and of genuine happiness in its highest sense.

3.4 THE BIBLICAL TYPE

In contrast to both the pagan and the pantheistic dependency ideas, the biblical arrangement denies that there is one continuous reality. The Hebrew idea of creation, which is basic also to Christianity and Islam, is that God (or Allah) the Creator is distinct from the universe which he brought into existence out of nothing. According to this teaching, the divine per se is not part of the universe nor is the universe part of the divine; there is a fundamental discontinuity between the creator and all else which is his creation. This basic difference has been well expressed by Will Herberg. Using the expression “Greco-Oriental” to cover both the pagan and the pantheistic dependency ideas, and the term “Hebraic” to refer to the biblical idea, Herberg says:

Hebraic and Greco-Oriental religion, as religion, agree in affirming some Absolute Reality as Ultimate, but differ fundamentally in what they say about this reality. To Greco-Oriental thought, whether mystical or philosophic, the ultimate reality is some primal un-personal force . . . some ineffable, immutable, impassive divine substance that pervades the universe or rather is the universe insofar as the latter is at all real. . . .

Nothing could be further from normative Hebraic religion. . . . As against the Greco-Oriental conception of immanence, of divinity permeating all things and constituting their reality, Hebraic religion affirms God as a transcendent person, who has indeed created the universe but who cannot without blasphemy be identified with it. Where Greco-Oriental religion sees a continuity between God and the universe, Hebraic religion insists on discontinuity.5

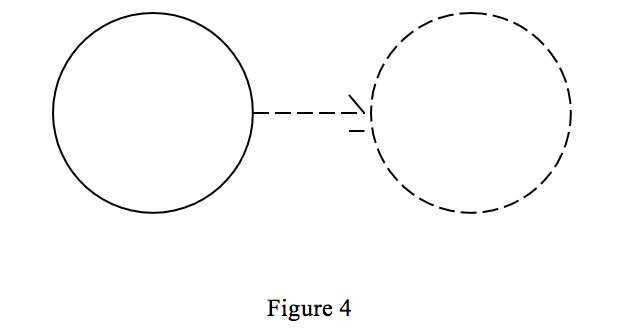

As a consequence, the biblical traditions neither exalt some part of creation to divine status nor dismiss the created universe as illusory. The universe is less real than God, of course, since it depends on God while God doesn’t depend on anything at all. But although dependent, the universe is real just because it has been created by God. And it is important because it is the arena in which humans are to live in fellowship with, and service to, God. Thus the created world is both important and wholly dependent; there is nothing about it which is not dependent on God. Every thing, event, and state of affairs; every part and property, fact and facet, law and norm — in short, everything other than God himself — has been brought into being by God and continues to depend on God, who is the only divinity there is. Figure 4 represents this biblical dependency arrangement.

It is because of this dependency arrangement that the idea of revelation is so important in the biblical traditions. God is not a reality whose nature and purposes can be discovered by searching the universe or by means of a mystical experience in the pantheistic sense. Instead, the biblical traditions are all anchored on the belief that God has created within the world an intelligible revelation of his relations to the universe, especially his relations to humans. This body of teaching is the authoritative guide for all knowledge of God (including the interpretation of unusual religious experiences). It teaches that only God is divine per se, and also conveys the contents of God’s covenant(s) of redemption which are the (type 3) secondary beliefs necessary for humans to stand in proper relation to him. By becoming subscribers to his covenant, or treaty of salvation, people become members of his Kingdom and receive eternal life. By contrast with pagan traditions, then, the religious experience which grounds theism does not find the divine to be any part or aspect of the natural world, but finds it to be revealed in a book. Hence the Muslim recognition that Jews and Christians, despite their differences from Muslims, are also “people of the book.”

And although biblical religion stresses the role of experience in a person’s belief in God, it does not require it to be a “mystical” experience in the sense that Hinduism or Buddhism require. On the biblical view, since God completely transcends creation, even experiences of unity with God are never taken to be with God’s essential being but are always mediated through (and to) something he has created. Still less does any experience lead to becoming part of God. The promised destiny of believers is not to be absorbed into God’s Being, since in the biblical religions humans are and always will be creatures distinct from God. It is distinct individuals, as members of the corporate body of God’s people, who are the objects of God’s love and forgiveness. And it is as individuals that they will be granted everlasting life in God’s final Kingdom. It is that fellowship with God, and with other humans who love God, that is the fulfillment of human nature and constitutes true human happiness. As one of the Christian catechisms puts it: “Question: What is the chief end of man? Answer: To glorify God and enjoy him forever.”

It is crucial to notice, however, that insisting upon the unbridgeable difference between God and creation does not mean that God cannot enter into creation and act in it; it does not mean he cannot be present with people, or that he cannot communicate with them. It simply means that his presence and communication are always accommodated to human understanding by being mediated through relations he creates and uses for that purpose. Nor does his communication usually set aside normal human faculties; he designed humans so that their capacities to experience and know would be able to receive his revelation as well as understand his world so as to serve him in it. So even when the biblical prophets had unusual experiences in connection with receiving revelation from God, that revelation was never something which abandoned ordinary human experience and reason altogether or showed the world to be merely illusion. On the biblical view the world does not conceal the divine, as is supposed by pantheism, but was formed so as to reveal God. (The reason people fail to recognize God’s revelation in nature and his word is called “sin” by Bible writers. We will return to this point presently.) Thus, while there is always that about God which is beyond human comprehension in biblical religion, humans are able to know truth about God because he has done two things: first, he has structured the universe so that, seen rightly, it points beyond itself to him as its transcendent, divine Origin; second, he has accommodated himself to human experience and reason and communicated his covenants of love, forgiveness, and everlasting life, throughout history. And this includes his bringing about a written record of those communications in scripture.

For these reasons, the experience of God is mediated through his revelation and is never an achievement of unaided human effort — as is taught in the pantheistic traditions. Thus the role of a biblical prophet is not that of a Hindu Swami or a Buddhist Master. In Hinduism or Buddhism the Masters are experts who by their own initiative have found the formula for experiencing the divine. By contrast, a biblical prophet is a deputy chosen by God to deliver his message; he is not an expert who discovered religious truth on his own, but a messenger to whom God revealed religious truth (in fact, the prophets often complained that they did not understand the message they were given). The initiative in all revelation is taken by God, not humans. Moreover, human religious experience itself is never the norm or standard of belief in biblical religions; rather it is the experience of recognizing God’s word as the norm and standard of belief. In other words, the experience itself is not the ultimate religious authority, God’s self-revelation is. And this is the reverse of the pantheistic idea of mystical experience, where the experience itself is the ultimate religious authority.

Corresponding to these differences about religious experience and revelation, there is yet another difference which is important. From the pantheistic outlook, a person must pursue the achievement of mystical experience through many lifetimes. Only when this is achieved will a person see the truth of the unity of all things, and thus attain release from the curse of endless rebirths by attaining Nirvana. But on the biblical view, the provisions of the covenant guarantee that directing one’s faith and love to God already assures the believer of salvation. It is a gift from God at the outset and not an achievement earned en route. The assurance of salvation is thus an integral part of being a Jew, Christian, or Muslim and does not come only after, and as a product of, lifetimes of struggle.

Of course, it is also true that there is struggle connected with serving God in daily life, according to biblical religion. There is effort and sometimes agony in trying to respond to the love God freely offers. And there is a deepening of faith in God and love toward others which can only come about with prayer and work, which are often accompanied by pain. Nevertheless, it is not the believer’s ultimate destiny which is at stake in the daily struggles to serve God, but only the closeness of the believer’s relationship to God and the degree of the reward God will ultimately bestow. For according to the biblical scriptures, any person who believes the truth of God’s revelation and loves God has already received the promise of God’s redemption and the gift of everlasting life.

To continue the contrast, we should notice that the biblical standpoint also has a distinctive view of human nature, which is even more antagonistic to the pagan and pantheistic views than those were to one another. In contrast to the most popular pagan view, the biblical teaching about what is wrong with people is not that they have a body, feelings, and emotions. According to Bible writers, people’s minds, bodies, emotions, thoughts, etc., may all be good or evil depending on whether they are used in the service of God. Once again, Herberg puts the point well:

However familiar and plausible [the] dualistic view may seem to many religious people today, it is nevertheless utterly contrary to the Hebraic outlook. In authentic Hebraism, man is not a compound of two “substances” but a dynamic unity. . . . The body, its impulses and passions, are not evil; as parts of God’s creation, they are innocent and, when properly ordered, positively good. Nor, on the other hand, is the human spirit the “false divinity” of the Greeks. Spirit is the source of both good and evil, for the spirit is will, freedom, decision.6

In this connection it is important to notice that the biblical idea of sin is not primarily that of moral wrongdoing. While immoral acts are, indeed, called “sins” (plural) and are condemned, the central idea of what is wrong with people according to biblical religion is religious. That is, “sin” (singular) is the name for the condition of human nature which causes people to fail to recognize the truth of God’s revelation, and thus fail to love and serve God with their whole being. This religious sense of “sin” is the putting something into the place of God, of having a false divinity rather than the true One. This is why the first demand of God’s covenant is we love him with all our heart, to which it then adds that we are to love our neighbor as ourselves for the reason that our neighbor is also created “in the image of God.” On the biblical view, then, sin is only secondarily a matter of immoral intentions and behavior. It is first of all a matter of not directing one’s faith and love to the Creator, and instead regarding something God has created as divine. As one Rabbi put it long ago:

God’s anger is revealed from heaven against all the ungodliness and wickedness of men who resist the truth . . . who changed the truth about God into a lie and worshiped and served what God created rather than the Creator. (Rom. 1:18)7

It is interesting to consider this quote from St. Paul in the light of the contrast between pagan and biblical religion which was drawn by a pagan thinker, Alfred North Whitehead. Whitehead quotes from the Bible the question, “Canst thou by searching find out God?” (Job 11:7). Recognizing that the text expects a negative answer, Whitehead makes the witty observation that this attitude is “good Hebrew but it is bad Greek”; that is, it is biblical but not pagan. He then adds the jibe that the biblical position is that of “thicker intellects” who “gloried in the notion that the foundations of the world were laid amid impenetrable fog.”8 Elsewhere Whitehead returns to this same point, this time rejecting both the biblical and the pantheistic standpoints in favor of the version of paganism which sees human reason as akin to the divine order of the world. He says:

What is the status of the enduring stability in the order of nature? There is the summary answer, which refers nature to some greater reality standing behind it. This reality occurs in the history of thought under many names, the Absolute, Brahma, the Order of Heaven, God. . . . My point is that any summary conclusion jumping from . . . such an order of nature to the easy assumption that there is an ultimate reality . . . constitutes the great refusal of rationality to assert its rights. We have to search whether nature does not in its very being show itself as selfexplanatory.9

This lucid contrast of (rationalist) pagan with biblical belief, stated on behalf of the pagan standpoint, comports perfectly both with the contrast drawn by St. Paul and with the schemas I have just offered. They all reflect the central differences between the dependency ideas held by pagans, pantheists, and theists. And they serve to confirm my point that pagan belief — at least in its non-ritual versions — is alive and well in Western thought and culture.

The contrasts just drawn between the three types of dependency ideas merely scratch the surface by comparing only a few of their most outstanding features. Nevertheless, they may be sufficient to reinforce three points that will be helpful in all that follows: (1) how widely beliefs differ over just what is divine per se and over how the divine relates to what is not divine; (2) why the types of these beliefs reviewed here are irreconcilable; and (3) how easy it is to fail to recognize a belief as religious when it comes in an alien form or from an unfamiliar tradition, especially if it has no worship attached to it.

3.5 WHY THINK ANYTHING IS DIVINE AT ALL?

Having now sketched the three major types of dependency arrangements found in present-day religious beliefs, I will end this chapter by returning to the question raised in chapter 1 as to whether anything at all is divine per se. The question is why someone couldn’t respond to all that’s been said so far this way: “I grant that you may have hit on what is essential to religious belief, and I even grant that such beliefs have played an important role in theories. But why isn’t that simply a regrettable fact, not an inevitable one? Why can’t we just try harder not to allow our theories to get larded over with religious beliefs? And why can’t we expand atheism so that it doesn’t only deny there are gods but denies that anything whatever is per se divine?”

The question as to whether theories can avoid including or presupposing some divinity belief will be taken up separately in chapter 10. For now, I will concentrate on the last part of the objection as to whether it is possible to defend the proposal “nothing is per se divine.” This, as we have seen, is the same as saying “nothing has non-dependent reality.” My reply is that this proposal has no coherent interpretation. Try as we will, I contend, we cannot specify any conceivable state of affairs in which nothing has the status of divinity. So while we may say the words “nothing is divine” and know what they mean, we can’t think of any set of circumstances that is an example of it — just as we can say and understand the words “square circle” but can’t think of anything they could name.

Perhaps the best candidate for a view of reality that lacks any per se divinity would be the claim that reality is composed only of individual things and events each of which is dependent. On this view each thing or event comes into being, interacts with other things and events, produces new things or events, and passes away. And for all we know, this succession of dependent things has been going on from all eternity so that it never had a beginning. In that case wouldn’t everything whatever be dependent? So isn’t this a conceivable state of affairs in which there are only dependent things and events? And doesn’t it therefore succeed in specifying a world in which nothing is divine?

The answer is that it does not. Even on this account there is something left in the status of divinity per se, despite the concerted effort to avoid it. What is left divine by this proposal is the total array of dependent things. Since according to the proposal, nothing exists other than the members of the total array, there is nothing for the array as a whole to depend on; there is nothing that explains why it exists; it just is. So it doesn’t matter to this proposal that each and every one of the things and events within the array is dependent, because the array as a whole is not and thus fits the definition of divinity per se. The question “why does the array exist rather than nothing?” is not answered. The total array is thus left by default in the status of having unconditional existence.

Sometimes it is replied that according to this proposal the array does depend on something, namely, its members. After all, it couldn’t exist without its members, right? This reply is seriously confused, however. The term “array” is a collective noun for all the dependent things that comprise the sort of reality being proposed, not the proper name of an individual thing. So the total array cannot be regarded as a single object that depends on its members as parts. In other words, the array doesn’t depend on its members; it just is its members. Thus suggesting the array depends on its members amounts only to saying that it depends on itself — which is nothing more than another (though less clear) way of saying that it’s non-dependent.

Let me put this rejection of “nothing at all is divine per se” another way in case it’s still not clear. The sum total of reality, no matter how that is understood, would have to be divine either in part or whole just because there’d be nothing else for it to depend on. The only way to avoid this conclusion would be to claim that “the sum total of reality” is somehow a nonsensical notion. But why think that? It seems to me I know what it means: it means all there is — whatever that may be. If what is independent is the sum total of reality taken as a whole, then some form of the pantheist dependency arrangement is right. If the sum total of reality is partly non-dependent and partly dependent, then either the pagan or the biblical dependency arrangement is right. Of these two, if the independent segment of reality is contained within and permeates the dependent segment, then it’s the pagan dependency arrangement that is correct. Whereas if the independent part of reality transcends (is not part of the being of) the dependent segment of reality, then the biblical dependency arrangement is the right one.

There are several things that should be noticed about this argument. The first I pointed out earlier when I said that the three dependency arrangements that are found in the past and present religions of the world are not the only possible ones. So I’ve been speaking of these three just because they in fact hold the field, and not on the assumption there couldn’t be others. Second, what I’ve been pointing out about them would be true no matter what fuller description may be held of that which has per se divine status. I’ve been speaking only of the dependency arrangements, not the alleged nature(s) of the per se divinities upon which the non-divine reality depends. It would be quite possible for someone to hold to any one of these arrangements, but substitute a different specific description of what has divine status from those taught by the religious traditions that have historically advocated that particular dependency arrangement. Third, this argument does not purport to show which dependency arrangement or which idea of what has per se divine status is correct. It shows only why it makes no sense to say that nothing has per se divine status, namely, we can’t so much as frame any idea of reality in which nothing is divine.

Finally, we should notice that this argument does not show that all people have some divinity belief. (I think that’s true; but I believe it because scripture teaches it, not because of this argument.) The fact that a belief has no coherent alternative doesn’t guarantee that everyone will in fact believe it.

This concludes our discussion of religious belief. We will now turn to the question of what a theory is and distinguish some major types of theories. This will help put us in a position to see why and how one or another description of per se divinity unavoidably plays a crucial regulative role in any abstract theory.