Reading: Chapter 5 - THEORIES AND RELIGION: THE ALTERNATIVES

Chapter 5 - THEORIES AND RELIGION: THE ALTERNATIVES

Dr. Roy A. Clouser

In this chapter I will give a brief sketch of the major positions which have been taken in the history of western thought concerning the general relation of divinity beliefs to theories. There are, of course, quite a number of variations within each of these positions, and these can be further combined into a wide variety of permutations. So the ideas outlined here should therefore be understood as the most basic alternatives stated in their simplest form.

5.1 RELIGIOUS IRRATIONALISM

The title I have given to this first alternative should not be taken to mean that every divinity belief is in some sense substandard or nonsensical when rationally assessed. Some advocates of this position do draw that conclusion, but others don’t. So the position itself is not necessarily a judgment on the truth of religious beliefs, but a view as to how, in general, such beliefs relate to any rational ground for them. Taken in this way the irrationalist view can be stated quite simply: it says that reason and divinity beliefs have nothing to do with one another. As a consequence, neither is capable of passing any judgment on the other. This means, among other things, that religious belief can neither be proven nor disproven. On this view, the fact that people have divinity beliefs is called their “faith,” which is taken to mean trusting the truth of a belief without having any justification for it (rather than the view that religious belief is based on experience, for which I argued earlier). This view sees faith as rationally blind trust which is an inexplicable fact, suspended in mid-air, with no strong connections to anything else — with the possible exception of ethics.

This position was neatly put to me on my very first day in graduate school. A tutor in the philosophy department asked me why I had come to the university and what my main interest was. When I replied that I was entering the philosophy of religion program, he winced in disappointment and remarked,

“Here at Harvard we teach philosophy and we teach religion. It’s up to you if you see any connection.” In fact, the way he put the point was mild in comparison with the way other thinkers have stated it. Some have held that religious belief and theoretical reasoning are so mutually inimical that the very attempt to give reasons for a faith destroys it. For example, Søren Kierkegaard said of those who want to explain or justify their faith in a rational way:

Would it not be better to stop with faith, and is it not revolting that everybody wants to go further? . . . Would it not be better that they should stand still at faith, and that he who stands should take heed lest he fall? For the movements of faith must constantly be made by virtue of the absurd.1

By calling faith “absurd,” Kierkegaard doesn’t only mean that it is not rationally justifiable, but that theoretical reason and faith are mutually exclusive:

Therefore it is certain and true that he who first invented the notion of defending Christianity . . . is de facto Judas number two.2

And again, at greater length:

Suppose a man wishes to acquire faith; let the comedy begin. He wishes to have faith but he wishes also to safeguard himself by means of an objective inquiry. . . . What happens?. . . It becomes probable, it becomes increasingly probable, it becomes extremely and emphatically probable. Now he is ready to believe it, and he ventures to claim for himself that he does not believe as shoemakers and tailors and simple folk believe, but only after long deliberation . . . and lo, now it has become precisely impossible to believe it. Anything that . . . is something he can almost know. . . it is impossible to believe. For the absurd is the object of faith, and the only object that can be believed.3

Another thinker who took this line was Friedrich Schleiermacher, an influential nineteenth-century German theologian. For Schleiermacher, religious belief was isolated from reason because religion is strictly a matter of feeling. So he defined religion as the sum of all higher feelings, and drew the consequence:

Wherefore it follows that ideas and principles are all foreign to religion. . . . If ideas and principles are to be anything, they must belong to knowledge which is a different department of life from religion.4

Thus Kierkegaard and Schleiermacher both see faith and theoretical reason as mutually exclusive, but whereas Schleiermacher thinks that reason cannot intrude into the realm of faith even if it wants to, Kierkegaard thinks that such intrusions are possible but are always destructive of faith.

I said that there can be a number of variations within each of the basic alternatives on the relation of religious belief and theoretical reason, and that is true of this first position as well as of the others. So just as the two thinkers just cited are not the only ones to have held it, neither are their versions the only variations on this position. But all its subscribers have in common the theme of disparaging the role of reason for religious belief; they all maintain that at best it can do no good, and at worst can do great harm. A diagram may help make this position clear.

Religious Belief is: Theoretical Reason is:

1. optional 1. religiously neutral and autonomous

2. isolated from it's realm 2. final court of appeal theoretical reason

There are two features of this position I want to call attention to before going on to look at the other alternatives. The first, indicated by the number 1 on the left side of the diagram, is that while every normal person has reason, faith is an option which may or may not be exercised.

The second feature is that although this position limits the scope of reason, it does not disparage reason altogether or advocate that we stop thinking. It is willing to go along with the highest estimation of the competency of reason in matters having to do with the rational side of life. It accepts that reason is the final court of appeal in these matters, that it is — in principle — neutral with respect to any outside influences and even autonomous (self-governing). Rather than disparaging reason, the position I call religious irrationalism simply maintains that there is a non-rational side to life which “leaves room for faith.” Since the niche thus left for religious belief is one into which reason cannot or ought not intrude, this position surrenders any hope of obtaining rational support for faith but gains in exchange immunity from any rational critique of faith. In return, the position likewise grants reason immunity from being censored by faith. The upshot is that on this view the two members of the relation are so walled off from one another that there cannot be a conflict between any article of faith and any theory of science or philosophy. The “department of life” in which theoretical reason is supreme does not overlap the area of life in which divinity beliefs are taken on faith.

5.2 RELIGIOUS RATIONALISM

Over against this irrationalist position, there is the alternative I call “religious rationalism.” On this position, all beliefs are to come before the judgment seat of rational inquiry, religious belief included. As the philosopher A. N. Whitehead once put it, “The appeal to reason is to the ultimate judge, universal and yet individual to each, to which all authority must bow.”5 On this position, no other consideration — no amount of trust, hope, feeling, etc. — is to be allowed as a competing authority to the verdict of reason, and no divinity belief is outside the competency of reason to judge it.

Religious rationalism thus agrees with religious irrationalism about the neutrality of reason, and differs only concerning the limits to reason’s scope. Both hold reason to be autonomous and that it is not, in principle, to be guided by anything other than its own rules. This does not mean that in fact people are always neutral and unbiased when they evaluate beliefs or construct theories, of course. But no matter how unsuccessful people may be in preventing extraneous influences from coloring their judgment, the rules of rational thinking and the procedures by which we make and evaluate theories are themselves neutral; they lead to unbiased conclusions if and when people keep from letting other influences interfere with them.

In some older versions of rationalism, reason was not only supposed to be neutral and the final court of appeal, but was also often thought to be competent to judge every issue whatever. Those who held this view did not mean that they actually possessed an explanation for each and every thing, but only that everything is in principle rationally decidable or knowable. This conviction was based on the belief that the orderliness which underlies the whole of reality is the same kind of orderliness that makes human rationality possible.

From the beginning, however, many rationalists hedged about this last point. Some doubted whether reality is completely ordered by logical or mathematical laws and thus open to rational explanation. So they doubted that human reason has the power — even in principle — to decide every question. Today there are few, if any, who would disagree with their doubt. But religious rationalists do not need to claim that reason is omni-competent in order to maintain their position. All they need to deny is that it is legitimate to hold any belief reason cannot decide. Instead of allowing a niche for the beliefs not rationally decidable, they demand that we suspend belief in all such cases. More to the point, they insist that religious belief is one of the issues theoretical reason can decide. Diagrammatically, the position that religious belief depends upon the verdict of theoretical reason can be represented as in the following figure.

Being a rationalist about the relation of theoretical reasoning to religious belief does not, all by itself, assure what a given thinker will conclude reason’s

Religious Belief is:

1. a theory or conclusion of reason

2. optional

↑

Theoretical Reason is:

1. neutral respecting all matters

2. final court of appeal in all matters

3. able to decide all matters (?)

verdict on religious belief is. One of the great champions of this position was Plato, who concluded that reason provides proof of (his) religious beliefs. By being rational, he says,

We are assured that there are two things which lead men to believe in the gods. . . . One is the argument about the soul. . . . That it is the eldest and most divine of all things. . . . The other was an argument from the order of the motion of the stars and of all things under the domination of the mind which ordered the universe. (Laws XII, 966)

But the same rationalist position was also held by the twentieth-century thinker Bertrand Russell, who arrived at quite a different conclusion:

So far as scientific evidence goes, the universe has crawled by slow stages to a somewhat pitiful result on this earth and is going to crawl by still more pitiful stages to a condition of universal death. If this is to be taken as evidence of purpose, I can only say that the purpose is one that does not appeal to me. I see no reason, therefore, to believe in any sort of God, however vague and however attenuated.6

Among those holding the rationalist position, there has been a definite trend over the last three centuries away from Plato’s conclusion and toward Russell’s. As a result, many who hold this view now take it for granted that reason has refuted religious belief and replaced it with the theories of science and philosophy.

Before going to the next alternative view, it is worth noting that both rationalism and irrationalism agree on a point noted earlier, i.e., that not everyone has a religious belief. For both positions, it’s a matter of choice whether or not someone holds a divinity belief, and if so, what that belief is. The rationalist opposes the irrationalist only by insisting that divinity beliefs are to be judged by rational procedures, and are not otherwise legitimate.

5.3 THE RADICALLY BIBLICAL POSITION

By calling this position “radically” biblical I do not mean to suggest that it is an extreme or bizarre view, but only that it is the view found in the Bible writers themselves. The term “radical” is thus meant here in its literal sense of “roots” and is synonymous with “strictly biblical.” We need to distinguish this position for two reasons. One is that it’s the view I intend to defend. The other is that we need to be clear about it in order to understand the last view to be covered, which is the one most theists in philosophy and science have held. That last view is a combination of the strictly biblical and the rationalist positions.

The rationalist position was the dominant influence in ancient Greco-Roman culture when the rise and spread of Christianity introduced belief in another authority onto the world scene. The biblical religions (at that time only Judaism and Christianity) denied that reason is the final authority or that reason is the only or best way to all truth. They taught instead that while reason is important, its highest function is to enable humans to understand the revelation of God and to serve him on the basis of what he has revealed. Accordingly, most Jewish and Christian (and later on, Muslim) thinkers have rejected the rationalist position. Even those among them who tried to remain as close to rationalism as possible had to deal in some way with relating reason to the word of God as another, distinct, authority.

As I said, most theistic thinkers today hold a combination of the strictly biblical position and the rationalist position. In fact, that combination has had such a wide hegemony for so long that many who hold to it have lost sight of the strictly biblical position so thoroughly that they usually deny there is one. They hold instead that Bible writers never take any position on a topic as abstract as the relation of belief in God to theories, so that there is no biblical position on this topic at all. Since this mistake is so widespread, I want to take some time to show that there is in fact a position taken on the subject to be found in the Psalms, the Prophets, and the New Testament. The position is this: there is no knowledge or truth that is neutral with respect to belief in God. The writers who assert this do not also specify exactly how belief in God impacts “knowledge of all kinds” or “all truth,” but they are clear that they regard beliefs in other (putative) divinities as partially falsifying all that is taken to be truth or knowledge, and that knowing God enables us, in principle, to avoid that partial falsehood.

There are a number of texts where Bible writers assert that knowing God is the “principle part of wisdom and knowledge,” but many of them occur in poetic works and so are usually dismissed as hyperbole (Ps. 111:10; Prov. 1:7, 9:10, 15:33; Jer. 8:9). So I’ll pass them by for now with the comment that they may just as likely not be hyperbole, and that the later development of this topic by New Testament writers shows they’re not.

One such later development is Jesus’ remark that those who distort the law of God have “taken away the key to knowledge” (Luke 11:52). Notice he does not say that distortions of God’s word take away the key to the knowledge of God; he just says “knowledge.” Those who maintain the view that the Bible never speaks to anything as philosophical as Jesus seems to do here might want to reply that his remark is elliptical, so that it’s a short-cut way of speaking of the knowledge of God, even though the phrase “of God” is omitted. But compare Jesus’ comment to 1 Cor. 1:5, where St. Paul says that knowing God through Christ has enriched us with respect to “all wisdom and knowledge.” That doesn’t sound elliptical nor is it poetry. And it can’t just refer to the knowledge of God. For later in the same book (12:8), he speaks of the various gifts God gives to believers and mentions specifically the gift of knowledge. Then in chapter 13 he says that this gift of knowledge will pass away along with other gifts such as prophecy, while the knowledge of God will be perfected so that we will know God by direct acquaintance just as God knows us. Hence the gift of knowledge — the knowledge that results from a talent bestowed by God and which is impacted by knowing God — is not (redundantly) only the knowledge of God himself.

In addition, it’s important to notice the way Bible writers use the metaphor of light to stand for truth, and use “being enlightened” to mean acquiring knowledge. Psalm 43:3 explicitly confirms this usage when it petitions God to “send out your light, even truth.” So when Ps. 36:9 asserts that “in [God’s] light we see light,” it sounds prima facie as though it’s saying the same thing as Jesus did and which 1 Cor. 1:5 affirmed, namely, that the knowledge of God plays a key role in the acquisition of all other kinds of knowledge. The light metaphor is continued in the New Testament. For example, 2 Cor. 4:3-6 says that unbelievers are blind to the light of the gospel and affirms again that this “light” is “the knowledge of God.” With this in mind, the clear statement of Eph. 5:9 is perhaps the strongest statement of all on the relation of belief in God to every sort of knowledge. It says that the consequences of the light of the gospel are to found “in all that is good, just, and true.”

I conclude, therefore, that the cumulative effect of these texts is to teach that no sort of knowledge is religiously neutral. This is what I take to be the “radically” or strictly biblical position. And since it is said to hold for all truth and for knowledge “of every sort,” it applies to the knowledge gained by theories as well as to knowledge acquired in any other way. I have already briefly sketched, in chapter 4, my account of Dooyeweerd’s proposal as to how this is to be understood. There I pointed out how our concepts of experienced objects (such as a saltshaker), or of entities postulated by theories (such as an atom), reflect divinity beliefs. In chapter 10 I will defend this proposal in greater detail, including the argument as to why divinity commitments are unavoidable. And in the final chapters I will explain Dooyeweerd’s proposal for how belief in God, specifically, should impact them.

This position on the general relation of divinity beliefs to theories can be represented diagrammatically as follows:

Theoretical Reason is:

1. not neutral because controlled by religious belief

2. not final court of appeal

3. not able to decide all matters

↑

Religious Belief

1. guides and directs the use of reason in all of life

By way of comparison, we should notice that the radically biblical position differs from both previous positions with respect to whether religious belief is optional. Rather than speaking of divinity belief as something a person may or may not have, Bible writers always regard everyone as having some divinity belief or other. According to them, what is wrong with people is not that they lack religious belief, but that they believe in the wrong divinity. On this position, then, being religious is as natural a part of every human as is being rational or being sentient; it can be exercised rightly or wrongly, but cannot be dispensed with altogether.

It is fair to ask at this point whether, on this position, it is wrong-headed for theists to try to justify their belief in God rationally. I think the biblical position is that it is neither possible nor desirable to attempt any theoretical justification of belief in God in order to convince an unbeliever. But I would hasten to add that this does not rule out critically reflecting on one’s faith in order to understand its teachings better, or to compare them with the teachings of other faiths. Nor does it mean that rational discussion with non-theists is totally useless. It can clarify biblical teachings for unbelievers as well as for ourselves, and allow replies to be made to criticisms of those teachings. Therefore I do not see the position of the Bible writers as the rejection of all reasoning in connection with belief in God. Rather, it is that we ought not to expect that non-theists will become believers in God by rational persuasion alone, nor ought we to think that we must have some sort of argument for our belief in God if it is to be intellectually respectable. This last point should not be misunderstood as some sort of fideism, however, but refers back to my contention that all divinity beliefs are based upon experience rather than inference. Calvin put this position well when he said:

Scripture, carrying its own evidence along with it, deigns not to submit to proofs and arguments, but owes the full conviction with which we ought to receive it to the testimony of the Spirit of God. (Institutes, I, vii, 5)

Thus, despite rejecting the demand for an inferential justification of belief in God, the biblical position does not ask for blind adherence. Nor does the appeal to experience require bizarre experience. The furniture does not need to fly around the room for one to have a religious experience. Rather, the experience I refer to is that of seeing the biblical message to be self-evidently the truth about God from God. (Recall the quotes of Calvin and the note on Pascal from chapter 2.)

This position therefore disagrees with religious irrationalism by denying that belief in God is either blind trust or walled off from rationality. On the contrary, it holds that one or another divinity belief always directs the way people use rationality to interpret the whole range of their experience, so that the full truth about any subject matter does indeed depend on having the right divinity. Notice that these two teachings — the religious control of theoretical thinking and the denial of the need to justify faith — are importantly connected. For if a religious belief controls and directs reasoning, it follows that all theoretical attempts to prove or discredit any divinity belief would, even if formally valid, fail to be religiously neutral and thus beg the question. In other words, any attempt to give, say, a convincing proof of God to those who have some other divinity would be futile because for theists belief in God is a presupposition to, and sets the limits for, how all else is interpreted including the premises of the proof. And the same would be true of any proof of a contrary divinity belief: it would also regulate how all else is interpreted by those with that divinity belief. Pascal has put this point well: to those who believe no proof is necessary, to those who do not no proof is possible.

It is this radically biblical position I will be defending in all that follows. I will maintain that the exercise of theoretical reason is always regulated and directed by some per se divinity belief so that reason is not autonomous nor is theorizing religiously neutral. If divinity belief is called “faith,” then according to this view faith is not a distinct faculty of the mind separate from the faculty of reason but an integral part of reason. It claims that rational intuitions of self-evidency are not confined to logical and mathematical axioms, but always include some intuition of divinity as well. The result is that reason is essentially faith-directed for all people.

But to distinguish this view fully, it must now be contrasted with the most popular position, the one briefly mentioned earlier. This is the position that insists that faith and reason are, indeed, separate faculties so that there are distinct realms for the authority of reason and the authority of faith. As we already noted, this alternative does not completely wall off faith and reason as irrationalism does, but sees the two related in a much more complex way.

5.4 RELIGIOUS SCHOLASTICISM

As was already admitted, the radically biblical position has not been held by the majority of Jewish or Christian thinkers. Long before the rise of Christianity, there were strong differences of opinion among Jews concerning the proper attitude to take toward the relation of their faith to the rest of life, particularly toward the dominant pagan, rationalist culture of the Greco-Roman world. Some Jewish scholars utterly rejected that culture as incompatible with what it meant to be a Jew, while others thought that most of ancient culture could be acceptable. On the latter view, all that was needed to be truly Jewish was to maintain the worship of the true God and the requirements of the Law of Moses over against pagan polytheism and loose morality. In other words, the second of these two opinions saw most of life and culture as religiously neutral, so that being distinctively Jewish was restricted to faith and morals. Among scholars it was this second view that prevailed.

The same issue faced early Christians as well, and there arose the same differences of opinion among Christians that had divided Jews. Some scholars and theologians thought that an unbridgeable chasm separated the entire Judeo-Christian tradition from the ancient world culture. They saw the effects of their faith on the rest of life as all-encompassing. One of them, Tertullian, referring to the biblical outlook as that of “Jerusalem” and the dominant culture as the outlook of “Athens,” asked, “What has Jerusalem to do with Athens?” But the majority of Christian scholars followed the predominant Jewish view, and thought the culture of their day was not so much wrong as incomplete. They regarded science, philosophy, art, law, etc., as the products of religiously neutral reason and thus not necessarily reflective of the pagan culture in which they had arisen. (After all, doesn’t 1 + 1 = 2 for a pagan as well as for those who believe in God?) So they adopted the attitude that, except for their belief in God and the need to correct pagan morals by biblical standards, Christians could accept most of the culture of their day without compunction. In short, they took the position that there is no radical opposition between biblical religion and any particular culture, since most of life is religiously neutral. Thus they adopted the view that the proper understanding of most aspects of one’s culture does not differ depending on what one’s religion is. So they took the biblical texts we just examined to mean that only religious wisdom and knowledge depend on having the true God.

This interpretation came to dominate the thinking of most theologians in the first few centuries after the rise and spread of Christianity. Because it was eventually developed brilliantly in the work of a number of theologians and philosophers who were professors, it later came to be called the position of the “school men” or “scholastics,” and still later was simply called “scholasticism.” The elaboration of this position by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century was so brilliantly and extensively worked out, and subsequently so influential, that many historians and philosophers now use the term “scholasticism” as a name for only Thomas’s theories or theories very like his. In what follows, however, I will not be referring to any particular group of theories or style of theorizing in my use of “scholasticism,” and still less will I be referring only to theories which are heavily Aristotelian as Thomas’s were. Nor will I be concerned with the extent to which the scholastic influence that now prevails can truly be attributed to Thomas himself. Instead I am using the term for the position that understands the general relation of divinity beliefs to theories as corresponding to two very different kinds of information: beliefs which are the deliverances of reason, and beliefs which are the deliverances of revelation accepted by faith, where faith is understood to be a distinct mental faculty from reason.

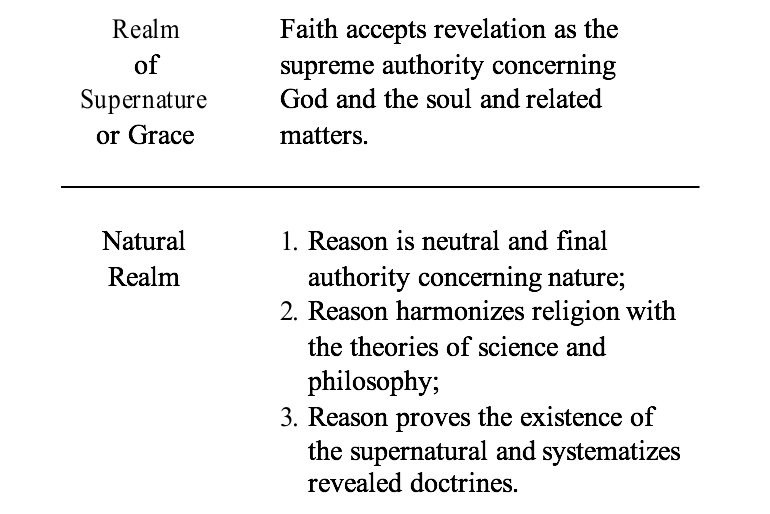

Since this view sees both faith and reason as genuine authorities, it emphasizes the need to harmonize their deliverances so as to avoid contradiction between them. And the task of keeping them in harmony, said St. Thomas, falls to theology. Another way of putting this position is to say that it devised a compromise between the all-encompassing claim pagan rationalism made for reason, and the equally all-encompassing biblical claim that right faith is a necessary prerequisite for knowledge of every sort. This was done by limiting the scope of each claim. The key to the compromise was to appeal to the biblical teaching that there are two dimensions of creation, which the Bible calls “heaven” and “earth.” The proposal was that each of these dimensions be taken as known in a different way, one by reason and the other by faith. The dimension of “earth” was called “nature” and was held to be the dimension of reality known by perception and reason. Such knowledge was held to be the same for all people. Concerning nature, reason was thus taken to be all that the rationalists said it was: neutral, and the final authority for all truth. The heavenly dimension of reality was called “supernature,” and was taken to be known only by revelation from God which must be accepted on faith. These revealed truths conveyed knowledge not provable by reason, such as information about God, the nature of the human soul, angels, and life after death. These truths are therefore not available to all people but only those to whom God’s grace has given the gift of faith. For without faith to accept revelation, reason is relatively helpless to discover truth about the supernatural realm. (I say “relatively helpless” because most scholastic thinkers held that reason unaided by revelation could prove that God exists and that humans have a soul, but nothing more. It could not, e.g., show how humans come to stand in proper relation to God.) In this way, each all-encompassing claim is in one sense discarded and in another sense retained: neither reason nor faith is truly all-encompassing in just the ways maintained by pagan rationalists and Bible writers, but each is the supreme authority in its own realm.

It should be especially noted that on this view faith is not blind trust as it is for the irrationalist. Rather it is a special faculty for apprehending revealed truth, and a means of acquiring certainty. So the scholastic position should not be confused with the irrationalist in any respect; while it agrees that the claims of rationalism are true for the realm of nature, it does not pair that agreement with an irrationalist view of faith. Moreover, whereas the irrationalist position walls off the rational side of life from that of faith, scholasticism sees the divide between faith and reason as a semi-permeable membrane, not a wall. There is a two-way interaction between faith and reason. Perhaps the best way to think of this interaction is to say that on this position faith and reason each have duties toward one another; each has its own proper domain, but each also affects the other. For example, reason not only discovers truth about nature and proves the existence of a supernatural realm, but also systematizes revealed doctrines and checks all rational theories for their compatibility with those doctrines. This is the task of theology. In case a theory of philosophy or science is found to be irreconcilably in contradiction with revealed truth, that theory is then to be discarded as false. The duty of faith toward reason is thus to supply an external check on whether reason has fallen into error, and it is seen as an advantage for reason to have such infallible truths by which to test its hypotheses. In the final analysis, therefore, the authority of revelation taken on faith is superior to that of reason alone.

But despite maintaining faith as superior to reason, this position still falls short of the strictly biblical one. It holds reason to be autonomous in the realm of nature, whereas Bible writers take it that having the right divinity belief is a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for understanding nature, as well as supernature. Moreover, it is clear that on this position most theories and many other sorts of knowledge and truth are religiously neutral. So long as they do not contradict any revealed truth, they need not be impacted by belief in God— or any other divinity — at all.

As a result, the dominant issue for scholastic thinkers has always been how to construe the relation between faith and reason, nature and supernature, so as to harmonize any potential conflict between them. For although the main distinctions of the scholastic scheme seem sharp and clear in a brief outline such as this, in practice they generated endless messy debates over just how to apply them in particular cases. Diagrammatically, scholasticism’s main distinctions can be represented this way:

Despite the many disagreements over the details of how faith and reason interact in specific cases, a wide consensus emerged among scholastic thinkers on a number of main points. First of all, while all humans are naturally rational beings, not all have the faculty of faith, so they agree on this point with both the irrationalist and the rationalist positions. The faculty of faith comes to a person as a gift from God, which is an addition to what a human is naturally. Speaking of the reception of the faculty of faith as a gift of God’s grace, Thomas Aquinas put the point this way:

Nobody receives grace of himself howsoever he prepares himself, even though he does all that lies in his power. . . . For grace surpasses all human effort. . . . If it be God’s will to touch the heart then grace will infallibly follow. (Summa Theologica 1a-11ae, q. 112, a. 3)

This addition of faith does not displace a person’s reason, as we saw, but supplements it. Here, again, is Aquinas:

The gifts of Grace are added to us in order to enhance the gifts of nature, not to take them away. The native light of reason is not obliterated by the light of faith. . . . The principles of reason are the foundations of philosophy [and science], the principles of faith are the foundation of Christian Theology. The truths of philosophy . . . cannot be contrary to the truths of faith. . . . Nature is the prelude to grace. It is the abuse of science and philosophy which provoke statements against faith. 7

Thus the guidance that faith offers to reason is a largely negative and external check on what reason may accept. It is not seen as an internally regulating influence. For were the influence of truths learned by faith internal to the operation of reason, reason would no longer be religiously neutral and autonomous. And were it not neutral, there would be no religiously neutral theories concerning nature that could be held in common with people who lack faith. Since scholasticism regards it as true that there are theories and other truths held in common by all people, it maintains that reasoning about nature must be neutral, and so it insists on a sharp difference between what can be learned by faith and what can be known by reason. What is more, if reason were not neutral it could not offer compelling proof that there is a supernatural realm. But, says scholasticism, reason can indeed provide rational evidence that there is a supernatural realm by proving the existence of God and the human soul. In this way reason points to a realm that needs to be revealed by God if we are to know more about it.

This last point might appear to blur the boundary between faith and reason, so Aquinas explained it to mean that there is a bit of overlap: certain items available to reason were revealed by God anyway so that those of weaker intellect would be sure not to miss them. But since they are knowable by reason alone, these items are therefore not — strictly speaking — articles of faith. So Aquinas says:

That God exists, and other such theological truths which can be known by natural reason are not articles of faith, but preambles to the Creed: faith presupposes reason as grace presupposes nature. (Summa Theologica la, q. 2, a. 2, ad 1)

Because scholasticism leaves such a wide latitude for both faith and reason while still admitting a strong interaction between them, its advocates find it difficult to see why they should adhere to the radically biblical view. They continue to take the claims about belief in God impacting all knowledge to mean all knowledge about the supernatural realm, and they point especially to knowledge in math, logic, and physics as examples of truths held in common by all people.

Finally, this view admits that theories which explain creation as dependent on one or another of its aspects would reflect a pagan religious belief if they ended simply with the position that all things depend on aspect X. But the paganism of such a position is easily avoided, says scholasticism. All we need do is to add to any such theory an additional claim: that although all the rest of creation depends on aspect X, X in turn depends on God. With that additional stipulation, the pagan character of such theories is neutralized.

The first part of my objection to scholasticism has already been given. It concerned the way scripture views all truth as (somehow) impacted by having the right God. That implies a stronger position than simply disallowing those theories that flatly contradict revealed truth. That a theory can’t be right if it contradicts revealed truth is true enough for any theist; but it’s not nearly strong enough to capture the biblical teaching. For no matter how assiduously that rule is applied it still leaves the vast majority of theories (and many other beliefs) untouched by belief in God. The majority of theories on almost every topic fail to contradict revealed doctrine and so turn out to be religiously neutral in exactly the sense the biblical teaching denies. But in that case, the rule that only theories which flatly contradict revealed truth are to be ruled out fails its own requirement! So despite scholasticism’s insistence that the authority of faith is superior to that of reason, and that revealed truth about supernature is more important than truth about nature, the scholastic rule alone is too weak to capture the biblical position on the relation of religious belief to reason.

This same failure is also what is objectionable about the scholastic ploy for neutralizing the pagan character of a theory that explains all creation as identical with, or dependent on, one or another of its aspects. That would be a pagan position, says scholasticism, without the additional claim that any aspect of creation proposed as what the rest of creation depends on, in turn, depends on God. But with that claim, what would otherwise be a pagan divinity belief is baptized (or circumcised) into theistic acceptability. My objection to this ploy is that the real explanatory power of the theory lies solely with the aspect that is taken to explain the rest of creation, not with God. The explanatory power of the theory is no different with the additional claim of God’s existence than it would be without it (unless miracles of God are made the dumping ground for what the theory can’t explain at all!). The additional claim is therefore another way of ignoring (or denying) the biblical teaching that no knowledge or truth is unaffected by belief in God.

Yet another objection to the scholastic view is that it denies the scriptural view of humans as naturally religious beings. Scripture insists that humans were created for fellowship with God and, as I pointed out earlier, Bible writers always address their readers as though they (the readers) believe either in God or some God surrogate. This is why the Psalms say that anyone who insists there is nothing divine is a fool (“The fool has said in his heart ‘There is no god’ ”); it is because all the while a person asserts that, the same person is in fact regarding something as divine. So the radically biblical position cannot agree that having faith is a “donum superadditum” — a power added to the natural faculties of a person that was not there from birth. The gift of God’s grace is not that of adding a previously missing faculty, but the redirecting and repairing of a malfunctioning one. As Calvin puts it, we are made so that we would naturally have “both confidence in him, and a desire of cleaving to him, did not the depravity of the human mind lead it away from the proper course of investigation” (Institutes, I, ii, 2).

Furthermore, the radically biblical position denies that the two dimensions of creation are each known by a different human faculty. Both God and creation are known by the same faculty, namely, reason which is by its very nature always directed by some divinity belief. This is not to suggest, of course, that there is nothing distinctive about the ways we use reason to know creation and the ways we use it to know God. Since God is not a part of creation, he must reveal himself if we are to know him. In addition, there is the effect of the Fall into sin on human reason. This is said to be a condition of humans in which their reason malfunctions with respect to what they experience as divine, so that their self-evidency antennae must be restored to proper working order if reason is ever to recognize God’s revelation for what it is. The same holds for the way nature can “witness” to God. Psalm 19:1 and Romans 1:20 tell us that nature — seen rightly — would display its dependent creatureliness. But reason misdirected by false faith does not correctly read nature’s display. It instead represses what would otherwise be obvious, and regards something other than God as divine (Rom. 1:25). This can only be remedied by the restoration of reason to its proper working order, so that God’s word is seen for what it is and so that nature is correctly interpreted. As Calvin once remarked, scripture provides the spectacles through which the book of nature must be read.

5.5 THE CONFLICT OF THESE ALTERNATIVES

The scholastic outlook sketched above had permeated the whole of European thought by the sixth century and was eventually adopted by virtually every leading Jewish and Christian thinker. Later on, it was also adopted by a number of influential Muslim thinkers.8 Corresponding to the division of knowledge into natural and supernatural realms, this outlook saw all of life as divided in two. Every issue was either a matter of faith or reason, the sacred or the secular, the soul or the body. Thus life was neither completely unified nor highly diversified. Everything was either a matter of the supernatural in which faith is the supreme authority, the destiny of one’s soul is at stake, and the church the representative institution of the supernatural on earth; or it was a matter of nature in which reason is the supreme authority, one’s bodily welfare is at stake, and the state is the authoritative institution.

Among thinkers who believe in God, scholasticism is still by far the most popular position in the world today. Its subscribers in religious studies, philosophy, science, art, and literature still outnumber any one of the other three positions, but it no longer has the almost total adherence that it did between roughly A.D. 500-1500. More importantly, it is no longer the leading outlook of Western culture. This loss of leadership came about in the sixteenth century when scholasticism was simultaneously challenged by two movements. One of these, the Renaissance, advocated a return to pagan rationalism by insisting on the autonomy and neutrality of reason in all matters, so that it dispensed with faith imposing any limit to reason. The other was the Reformation, part of which rejected limiting faith to only supernatural matters and argued that reason is intrinsically guided by faith in all matters.

The revival of the rationalistic position was abetted by the gradual rediscovery of the accomplishments of the ancient world. The scholars involved in this rediscovery came to regard ancient culture as superior to their own and in time began to refer to the era between the fall of Rome and themselves as a “middle age,” that is, a period between the last great culture and the next one they hoped to usher in. They saw themselves as the defenders of reason who, by the revival of rationalism, would bring back “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome” by restoring the supreme command of reason. (Nineteenth-century historians who agreed with them began to call their movement a “Renaissance,” a rebirth of the freedom of reason to rebuild the greatness of Western civilization.) These Renaissance thinkers called for a new outlook which did not set limits beforehand to what reason could or could not accept, and which did not constantly point to a realm of supernature as more important than the natural world. They confidently predicted that if their outlook were given free rein, they could begin to create paradise here and now instead of simply hoping for it after death. And beginning in the latter part of the sixteenth century and throughout the whole of the seventeenth, they pointed to the remarkable advances of the sciences as evidence for these claims.

At the same time that this Renaissance movement was gaining momentum, the Reformation also challenged the scholastic establishment. It was unlike the Renaissance in that it came from within the church, and the reverse of it in advocating that religious belief underlay theoretical reason rather than needing a rational proof. Although the flavor of this movement differed somewhat depending on its leaders in various localities, one of the clear thrusts of the movement was an attempt to revive the radically biblical position. The leading Reformers — Luther, and especially Calvin, and their associates — saw the word of God as permeating and transforming the whole of life; for them it was not merely an external constraint or check on reason but its internal guide. Most of their efforts were understandably aimed at reformulating theology and reorganizing the church, but a fundamental conviction behind their reforms was the rejection of the scholastic partition of religious belief and reason.

In the course of his work, Luther reverted to the scholastic view on a number of issues, but Calvin carried forward the anti-scholastic strain of Luther’s thought. In commenting on the supposed religious neutrality of reason in the study of nature, e.g., Calvin said:

It is vain for any to reason . . . on the workmanship of the world, except those who . . . have learned to submit the whole of their intellectual wisdom (as Paul expresses it) to the foolishness of the cross. . . . The invisible kingdom of Christ fills all things and his spiritual grace is diffused through all.9

Throughout his writings, Calvin takes the view that human reason is not neutral because it is affected by sin, where sin is understood as false divinity belief which produces deleterious effects on reason’s attempts to interpret reality. As he sees it, false religious belief cannot help but produce distortions across the board, not just in theology and ethics. For that reason, when scripture reveals the true God it not only reveals the proper object of faith and worship, but restores the proper perspective for the operation of reason. To be sure, Calvin does not spell out exactly how belief in God does this, any more than the Bible writers themselves did. But I have already begun to lay the background for an account of Dooyeweerd’s explanation of this, and will carry that forward in the succeeding chapters of this book. I will formulate his specific form of this claim in chapter 6, and illustrate the influence of divinity beliefs on theories using examples drawn from math, physics, and psychology in chapters 7, 8, and 9. Then in chapter 10, I will explain both his arguments as to why religious regulation of theories is unavoidable, and his critique of the traditional (pagan) strategy for theories. In the last three chapters I will then spell out his program for theorizing on the basis of belief in God. This will take the form of showing how the doctrine that everything other than God depends on God leads to a distinctive theory of reality, and through that view of reality further leads to a distinctive interpretation of all concepts, including the hypotheses of the sciences.

When the Renaissance and Reformation came into head-on conflict with the entrenched scholasticism and with one another in the mid-sixteenth century, one of the first casualties of the conflict was the Reformers’ affirmation of the radically biblical teaching about the non-neutrality of the whole of life. Though many of the theological and ecclesiological reforms of Luther and Calvin were preserved in various branches of Protestantism, the non-neutrality doctrine was not preserved. In fact, the immediate successors to the leadership of the Reformation movement (Phillip Melanchthon and Theodore Beza, respectively) explicitly abandoned the idea that all knowledge is conditioned by religious belief and returned to the scholastic position. So even though Protestant and Catholic theologians continued to disagree over such items as the organization of the church, the interpretation of the sacraments, and papal authority, their general view of the relation of faith and reason was largely the same. Their main difference over faith and reason came to be that while Catholic thinkers tended to harmonize their faith with theories about nature derived from Aristotle (due to the influence of Thomas Aquinas), Protestant thinkers felt free to harmonize their faith with whatever theories about nature were currently fashionable. The result has been a virtual parade of Protestant scholastic combinations of belief in God with such theories as Cartesian dualism, phenomenalism, Kantian idealism, Hegelian monism, romanticism, Marxism, existentialism, etc. Meanwhile, the radically biblical position, though it survived in the work of a few individual thinkers and some small theological traditions, was marginalized by most of Protestant thought.

As a result, both camps of mainstream Western Christian thought, along with many Jewish and Muslim thinkers, still lack any appreciation of the religious control of the whole of life. Theories especially are thought to be religiously neutral rather than regulated by presupposing either God or a false divinity. Instead, belief in God is usually tacked on to the end of a theory like the tail on the birthday party donkey; rather than being a theory’s controlling presupposition, it is an afterthought intended only to neutralize its otherwise thoroughly pagan character. Consequently, most theistic thinkers continue to think that theory making proceeds in neutral fashion, and that a theist need only add to a theory the claim that God created whatever the theory proposes and check to see that nothing in the theory flatly contradicts any revealed truth. Thus the general relation of divinity beliefs to theories is seen as one of harmonization.

This, however, is in direct opposition to the radically biblical view we have already examined. From that viewpoint the project of harmonizing belief in God with any given theory is impossible unless that theory already presupposes God, and unnecessary if it does! For no theory that is self-assumptively coherent can fail to be in harmony with its own presuppositions, and incompatible with contrary presuppositions. By failing to recognize that if a theory does not presuppose belief in God it is not neutral but inevitably presupposes belief in some other (putative) divinity, scholasticism assumes theists are free to work out a peace treaty between their faith and any theory that sounds plausible and doesn’t outright contradict revealed truth. The radically biblical objection to this is, of course, that any supposed external harmony of a theory with belief in God is mere illusion so long as the explanatory strategy of a theory presupposes another, contrary, religious belief.

I’m now going to put a point in favor of this radically biblical position in the form of a question: if, as we shall soon see, all theories are regulated by one or another divinity belief in such a way that their interpretations differ relative to that belief, why would belief in God be the only exception? Why does it make an important difference to the content of a theory whether it presupposes matter, or sensations, or mathematical laws, or form/matter substances, or logical laws, etc., as divine, but fails to make any important difference only when God the Creator is taken as divine instead of any aspect of the creation? Surely that is prima facie implausible; nevertheless, it is the prevailing view.

Perhaps the main reason for the demise of the radically biblical position was the accomplishments of the sciences that were pointed to by Renaissance thinkers as evidence for their view. Around the time of the Reformation, and in the century and a half just after it, there was a series of stunning achievements that were touted as utterly neutral with respect to religious belief. These included the revival of algebra, the development of analytic geometry and the calculus, the invention of the microscope and telescope, the discovery of the laws of motion and gravitation, and the beginnings of comprehensive theories covering such fields as mechanics, optics, and astronomy. The fact that most of these accomplishments seemed to be true irrespective of one’s religious beliefs did more than just ratify the Protestant tradition’s surrender of its radically biblical element. Ultimately, it resulted in the triumph of the Renaissance revival of rationalism — first under the title “Humanism,” and later called “Enlightenment.” This position won the intellectual and cultural leadership of the Western world and has remained in that position to this day. Currently its biggest challenge comes from various versions of historicism, pragmatism, and relativism, which usually view religious belief in the irrationalist way.

In fact, in the last century and a half, the radically biblical position has been ever more eschewed by the Protestant tradition owing to the specific interpretation of it which has been advocated by the largest single group of its adherents, the fundamentalists. Fundamentalists have retained the idea that religious faith should guide the whole of life, theories included. They, too, see the guidance of religious belief as a matter of positive and internal direction, rather than merely a matter of forbidding theories to contradict theological doctrines. But their particular understanding of just how belief in God exercises its influence in theories is so implausible that it has resulted in bringing disrepute on the very notion of a radically biblical position for theories.

So now that I have said that the scholastics hold a numerical plurality, that the rationalists are in the driver’s seat, that the irrationalists are coming on as challengers, and that the largest group to hold the radically biblical position are fundamentalists, what can possibly be said in defense of this position? At least twice in history it has surfaced only to be given up by its own would-be champions. So why bring it up again?

The simple answer is that the radically biblical position cannot be plausibly interpreted as fundamentalists do, i.e., by deriving theories or confirmation for them from scripture or theology. I will shortly show how the role of abstraction of aspects in theorizing makes it inevitable that any theory presuppose some divinity belief. But before presenting the case for this position, we must clear up just what is meant by a religious belief’s “controlling,” “directing,” impacting, or “regulating” a theory by acting as a presupposition to it. Therefore, the next chapter will criticize the fundamentalist idea of religious control and present the idea of control which will be defended as the proper interpretation of the biblical teaching about the relation of divinity beliefs to theories.