Reading: Chapter 11 - A NON-REDUCTIONIST THEORY OF REALITY

Chapter 11 - A NON-REDUCTIONIST THEORY OF REALITY

Dr. Roy A. Clouser

11.1 THE PROJECT OF NON-REDUCTIONIST THEORIES

In chapter 6 I distinguished the radically biblical position from that of fundamentalism. I held that in one sense the fundamentalist’s claim is too strong because it assumes that scripture is like an encyclopedia containing revealed truths about every sort of subject matter. On such a position, God’s word is not the light to our path, but the path itself. It is this encyclopedic assumption that has led fundamentalists to imagine that the way theories should be impacted by belief in God is by having hypotheses be derived from, or confirmed by, truths which are extrapolated from scripture or inferred from scripture by theology. In opposition to this program, I maintained that scripture is not an encyclopedia and has little to say that can serve as content or confirmation for most theories of the natural sciences — though it does contain specific teachings that should be included in theories about human nature, society, and ethics. By contrast, I held that the most important influence of divinity beliefs on theories is both less direct and more pervasive, namely, that one or another of them always functions as a regulative presupposition that guides the formation of theories in both philosophy and the sciences. That guidance, I argued, is a two-step affair: the divinity belief sets the parameters for a perspectival overview of reality, which in turn delimits a range within which the nature ascribed to hypothetical entities will appear acceptable. Thus belief in God can regulate theory making even if scripture does not supply other specific teachings appropriate to the theory’s discipline.

At the same time, however, I maintained that the fundamentalist position is in another sense too weak. This is because it regards the influence of religious belief on theories as something which anyone may in fact do without. In opposition, I argued that no theory can ever be free of regulation by some divinity belief or other.

In the intervening chapters, we have seen a number of illustrations as to how religious presuppositions extend their control to scientific theories through theories of reality. In each case, however, the sample theories were all controlled by some version of non-biblical (pagan) religious belief; as yet I have provided no samples of how theories can differ by presupposing the biblical idea of God. The examples considered have nevertheless shown how religious presuppositions exert their influence, and thus prepared the way for seeing the sort of impact we can expect presupposing belief in God to make on theories once it replaces non-biblical divinity beliefs.

Since we found that religious presuppositions exert their influence on scientific theories via a theory of reality, it should be obvious why we are starting with a theory of reality in this chapter.1 But I should say right away that the chapters following this one will not then go on to develop theistic theories of mathematics, physics, and psychology. That is, they will not parallel the casebook chapters. There are two reasons for this. One is that I do not have the required expertise to do that job. The other is that the theory of reality we are about to examine cannot be adequately explained in one chapter, but must be developed by being applied to a number of diverse issues if its hypotheses and their consequences are to become clear. And the issues that most readers will find allow the theory to become clear are, I think, those of social and political theory rather than those of math or physics or psychology. Therefore, this chapter will present a blueprint for a theory of reality that presupposes God alone is divine, and the two following chapters will apply that blueprint first to a general theory of society and then more specifically to a theory of one social institution, the state.

For this reason, it is crucial that these chapters be read in the order in which they appear. I emphasize this because dealing with a new theory of reality may be an unfamiliar and difficult project for many readers. The very prospect may therefore tempt them to pass over this chapter to the chapters on society or politics whose titles sound more familiar and perhaps more interesting. But without the theistic theory of reality to guide social and political theories, it will not be obvious why their proposals should be regarded as the fruit of theism. Without such a theory of reality, there will be no intellectual scaffolding within which distinctively biblical theories may be constructed. Moreover, it is precisely the lack of just such a scaffolding that is the main reason why the efforts of so many Jewish, Christian, and Muslim thinkers have fallen short of producing truly theistic theories and ended up advocating essentially pagan theories with belief in God merely tacked on to them. So our procedure here will be to recast completely the project of a theory of reality, both as to the questions it poses as well as the answers it gives to them. For these reasons, bypassing the theory about to be sketched will result in leaving in the dark both the full character of the main proposals of the later theories and the reasons which recommend them. More than that, it will — as I said — render totally unclear why they are supposed to be distinctively theistic proposals at all.2

Before going ahead, we should take notice of some special difficulties this project encounters which do not plague pagan-based theorizing. The first of these is that a thinker whose theory making is directed by a pagan belief not only can be unaware of the religious character of his or her controlling presupposition, but can be unaware of the content of that presupposition altogether. In this way pagan religious beliefs not only may be assumed unconsciously, but may guide theory making while remaining unconscious. (This was not what was going on in the theories considered in the casebook chapters, of course. Those thinkers were all clear about the basic presuppositions which directed their theories, and some even acknowledged the religious character of them.) My point here is that while theories can be produced under the guidance of a pagan faith even when it is held unconsciously, the production of theories controlled and directed by belief in God will need more than unconscious guidance on the part of Jewish, Christian, or Muslim thinkers. Not only will it require conscious effort, but even the sincerest efforts of the ablest of thinkers may meet with only mixed success. There are at least three reasons for this.

The first is the unique way in which faith comes to those who believe in God. According to Bible writers, it comes about by the conjunction of two factors: contact with God’s revelation of himself and the operation of God’s grace which enables a person to see the truth of that revelation. Scripture everywhere represents this special grace as necessary because it must overcome the natural human inclination to regard something other than God as divine (this inclination is the true meaning of the Christian doctrine of “original sin”). Thus, while people may unconsciously regard all or part of the creation as divine, no one ever comes to faith in the transcendent Creator unconsciously.

The second reason is the way the residual effects of that sinful inclination make resisting the influences of unbiblical beliefs and attitudes a struggle within even the most committed believer. The greatest heroes of the biblical traditions had such struggles, and we who are their junior admirers can expect no less. So just as our religious weakness requires a conscious struggle for our personal attitudes and behavior to become permeated and controlled by our faith, so too it is a struggle to extend the influence of that faith to the task of making, evaluating, and reforming theories.

Finally, the difficulties of inventing or reforming theories on the basis of belief in God are made even greater by the influence of the long tradition of theists attempting to retain the pagan reduction strategy. Indeed, this view has been so dominant among theistic theorists for so long that it is very difficult to shake the habits of thought it produces — even for those who have come to see it as inadequate.

Because of both the innate and the traditional obstacles to constructing radically theistic theories, those who attempt this task cannot help but be painfully aware that their efforts may be seriously deficient despite their best intentions. This chapter and the next two chapters should not, therefore, be misunderstood as claiming to reflect the biblical perspective in some complete or final way. Nor does it claim to capture that perspective with perfect purity. Still less does it claim to have hit on the only hypotheses that could be developed from that perspective. Rather, the theories to be presented will be attempts to highlight the perspective itself by being guided by it.

This last point has some important consequences. The most obvious is that with respect to any particular theoretical question there may be several hypotheses possible which presuppose belief in God. Thus a hypothesis may be ever so properly directed by our faith and still simply be mistaken. In other words, when we embark on the task of making explanatory guesses we may be within the range and direction of biblically motivated thinking, but still simply be mistaken in the entity or short-range perspectival hypotheses we postulate. The counterpart to this point is that nonbelievers may theorize from a perspective that presupposes a false divinity but still make specific proposals which are importantly correct. We must always be open to learning from such theories, even though we must also strive to recast the interpretation of them from a theistic perspective. It would be a huge mistake, therefore, for believers in God to reject any theory in its entirety just because it presupposes a non-biblical faith. We need not, for instance, reject the whole of atomic theory and look for a replacement for it just because it has been advocated by materialists. But although a hypothesis may be controlled by a false divinity belief and still be correct in important ways, its false perspective on reality will guarantee that it will distort and partly falsify the nature of its proposals. Therefore our position is that while both biblically and non-theistically regulated entity hypotheses may turn out to be wholly false, no non-theistically directed hypothesis can ever be wholly true. Thus while a radically theistic approach to theories does not mandate all new hypothetical entities for every science, it does require that we rethink and reform the concepts of the nature of all hypothetical entities in a way which reflects a theistic, i.e., non-reductionist, perspective.

Let me warn you that rethinking a theory of reality in such a distinctively biblical direction of thought will lead us to some very new hypotheses. Many of them will sound strange compared to past attempts by theists to think about theory of reality — despite the fact that we all share belief in the same God.

Where this happens, I can only plead with my fellow believers to try to distance themselves from the influences of the tradition of adapting reductionist theories. No matter how difficult it may be, purifying our theories of pagan elements is obligatory for every theist. The only alternative is to abandon theorizing about God’s creation to those who presuppose it is not God’s creation. Our task, then, is to develop theories that are guided by our faith in God. It is not to theorize in order to supply credentials for our faith, still less is it merely to theorize so as to “leave room for faith.” It is not our belief in God that needs to be made intellectually respectable by means of theories, but our theories that need to be made religiously acceptable by being internally motivated and directed by our faith.

11.2 SOME GUIDING PRINCIPLES

The deep involvement of religious belief in both the strong and the weak versions of the reduction strategy has already been demonstrated. We have seen how each version tries to identify the basic nature of reality by reducing all its other aspects to the one or two chosen as its nature. The central idea of this strategy is that the essential nature of the cosmos can be found by identifying the aspect(s) which are independent and upon which all the others depend for existence. This is why using the vehicle of reduction to transport us to the goal of explaining the nature of things exacts the price of a pagan commitment: it ascribes divinity to some aspect(s) of the creation, which is flatly contrary to the biblical doctrine of God as the sole, transcendent creator and sustainer of every thing other than himself. Any theory which confers that status on anything other than God is thereby false and idolatrous. Therefore, it is this point I contend must be made the first guiding principle for a genuinely theistic perspective. It is the principle of pancreation defended in the last chapter: Everything other than God is His creation and nothing in creation, about creation, or true of creation is self-existent.

But this principle alone is not sufficient to distinguish the biblical perspective because it has so often been accepted by theories that nevertheless regard some aspect(s) of creation as generating the existence of all the other aspects. To protect the principle of universal creation from this distortion, a second guiding principle is required, the principle of irreducibility: No aspect of creation is to be regarded as either the only genuine aspect or as making the existence of any other possible or actual. This principle reflects the biblical view that all creation depends directly and equally on God, so that all genuine aspects (whatever the correct listing of them may be) are equally real. This latter principle, together with universal creationism, serves to bring into focus a more thoroughly theistic perspective. It does so by showing that belief in God permeates and controls our theories by requiring the complete abandonment of the reductionist strategies, rather than merely the eclectic rejection of objectionable elements in the contents of theories using those strategies.

But abandoning the strategy of reduction will not simply lead us to a different answer to the question of the basic nature of reality. It also results in a new way of framing the question itself. We will still want a theory that can account for our experience that various types of things have distinctive natures, of course. But we will not be seeking the basic nature of everything in the senses of “basic” used by the traditional reductionist theories. We will instead deny that any one aspect is more real than any other, or that any produces another. Thus, the pagan idea of “basic” will be ruled out of the quest for what things are, just as it will be ruled out of the quest for why things are. Instead, we must now invent or reinterpret theories in a way that is completely non-reductionist. This is not to deny that in our ordinary experience things of a particular type appear to share a specific nature which is more centrally characterized by certain of their aspects rather than by other aspects. But focusing on a particular aspect as telling us more about the nature of a particular type of things does not require a reductionist theory of reality. For example, a plant has physical properties as does a rock, but the plant is alive and the rock is not. In this way the nature of a plant is more centrally characterized by its biotic aspect than by any other aspect. This does not mean that its other aspects are to be reduced to its biotic aspect, however. It need only be the case that the laws of that aspect take the lead in governing the internal organization and development of a plant taken as a whole. Hence we may indeed characterize its nature as that of a living thing. In this way, we may single out the biotic aspect as telling us something “central” about the nature of a plant without requiring either that it has only biotic properties or that those properties generate some or all of its other aspects.

The further development of such a non-reductionist approach in the next section will open up some exciting directions for a theory of reality which were excluded by pagan presuppositions. If we no longer look for the nature of things by searching for which aspect all the others collapse to, or which produces all the others, then there need be no one basic aspectual nature of everything. There may be as many different “natures” to created reality as are needed to explain the types of things we experience. If this is so, we will be freed from the sorts of bizarre, implausible lengths to which modern reduction theories have been driven in trying to show that the most diverse types of things actually have the same basic nature. We may be delivered from such dead ends precisely by being released from the compulsion to find what it is in things which accounts for both their natures and what makes them real. So while knowing that God makes things to be what they are does not hand us a theory of reality, it does free us from ransacking the cosmos for the self-existent, divine reality that makes everything in it both possible and actual.

11.3 THE FRAMEWORK OF LAWS THEORY

We have already noticed that the various aspects displayed by the objects of experience and investigated by the sciences are not only kinds of properties, but kinds of laws. It is because of these laws that each aspect exhibits an orderliness among its properties such that its properties are experienced to be related as co-possible, mutually exclusive, or necessarily connected. For example, it is a law of the physical aspect that all sodium salts burn yellow, while it is a law of the spatial aspect that nothing can be both round and square. Without such an orderliness, creation as we know it could not exist, and without statements expressing such order, no explanatory theories about creation are possible. The law statements we formulate are therefore our approximations of specific links in the cosmic law-order. They express relations which, under specific conditions, are necessary in that they cannot be violated.

We already noticed that the idea of law is prominent in scripture, too, where it also has the sense of supplying order to things. The most prominent use of the term is, of course, in reference to the religious-moral law which has a central role in the covenant God made with Israel through Moses. But, as we saw, scripture also speaks of the orderliness of the universe at large, and says that the order (“ordinances”) of creation are established and maintained by God. And it adds, as part of God’s covenant promises, that He will faithfully preserve these laws.

Such biblical remarks are not offered in the precise technical language of philosophy or science, nor do they involve what I have called “high abstraction.” But they do emphasize a point which can be developed in a significant way for devising a theory of reality: they encourage the proposal that theists begin to rethink theory of reality by elaborating the idea of a framework of laws under which all created things exist and function. Scripture speaks of these laws as created, and therefore not to be regarded as identical with God. Nevertheless, they constitute the principles of order God has built into the creation, and which account or the orderliness we observe in the cosmos. They are the de re necessities by which His creation regulated.” This is not to suggest that laws are objects like planets, trees, or oceans, nor is it intended to mean that they exist separately from the things and events they govern (as Plato’s forms were supposed to). Rather, “law” is our term for the order God has embedded in his creation, and our theory will start by recognizing a distinct law-side to created reality. Moreover, since we have abandoned the reductionist strategies there will be no need to expect that the law framework will be made up of only one or two kinds of laws, or that some one or two kinds generate all the others. Instead, our theory can include all the different kinds of order we experience to exist, and regard them all as equally real components of a cosmic law framework.

There are several species of laws that will need to be distinguished as we pursue this approach. One of these is what we usually call “causal laws,”3 another is what I’ve been calling “aspectual laws,” while a third is what I will term a “type law.” Since we’ve already focused so intently on aspects of experience, let’s start with the laws that hold between properties of the same aspectual kind and treat type laws later. And since we’re now going to use that idea to develop a theory, let’s review again our provisional list of aspects so as to clarify several of its members:4

fiduciary ethical justitial aesthetic economic social linguistic historical logical sensory biotic physical kinetic spatial quantitative

I have tried to avoid nouns to designate the members of this list since nouns tend to promote the misunderstanding that these are classes or groups of things. Instead, I have used adjectives to emphasize that what are being listed are kinds of properties and laws exhibited by the things and events we experience. This has resulted in some odd terms and some special meanings for some familiar terms, so I need to comment briefly on some of them.

The term “quantitative” is used to designate the “how much” of things, and should not be misunderstood to refer to (the theory of) a realm of numbers or the abstract systems of mathematics devised for calculating quantity. There is evidence that some animals have a sense of quantity even though they cannot count,5 and it is just such an intuitive awareness of the “how much” of things that I am pointing to here. It is the experienced quantity of things that the science of mathematics abstracts as its field of inquiry. Within that field it then further abstracts the property of discrete quantity, which becomes the basis for the natural number series from which even more abstract and complex mathematical concepts are built up. Various branches of mathematics can then be developed corresponding to the different ways quantities can be calculated by formulating laws which hold among them. But all this stems from our intuitive recognition that things have quantity.

“Kinetic” is used to designate the movement of things, their motion in space. Many scientists include these properties and laws within the physical aspect, though Galileo seems not to have done that, and at least two contemporary thinkers have argued persuasively that it is actually a distinct aspect.6

The term “sensory” is used in the way explained in chapter 9, that is, to cover the qualities and laws of both perception (touch, taste, sight, smell, and sound) and of the feelings elicited by perception. They are included in the same aspect because perception and feeling are both ways in which humans and animals are sensitive.

The term “historical” also deserves some comment even though it is a familiar one. This is because so many people think of it as referring to everything that has happened in the past. That is not what is meant here. Nor is that the way historians use it either, since not everything that has happened is historically important. Judging from what interests historians, it appears that the difference between what is historically important and what is not is the same as what is significant to the formation of human culture and what is not. What history is about, then, is the transmission of culture-forming power. Thus our adjective “historical” will be virtually equivalent to “cultural.” And because forming a culture is based upon the ability to form new things from already existing materials, some philosophers have preferred the term “technological” for this aspect. No matter which term is used, what is important is that it be understood in the way I’ve just described, so I’ll be speaking of all the products of the human technical ability to form new things from natural materials as cultural (historical) artifacts.

The term “ethical” is not at all unusual as a general term referring to what is right and good or wrong and evil about human behavior and attitudes. Nevertheless, the term is often used to cover two very distinct senses of those terms: what is right or wrong according to justice, and what is right or wrong according to morality. In the list given above, these aspects are distinguished. The justitial aspect has to do with the norms that apply to our attitudes and actions concerning what is fair. By contrast, the ethical aspect as that term is used here has to do with norms that concern what is loving or beneficent. Although different, the two senses are, of course, related. Generally speaking, we may be just to someone without also being loving, but we cannot be loving to that person without being just. Love often bids us go beyond what someone legally deserves — as is illustrated by Jesus’ famous story of the Good Samaritan. But we would have to be at least as just to someone as circumstances permit before we could succeed in being loving to that person. Our view of the ethical aspect could therefore be called a “love ethic,” but in a much stronger sense than that expression is usually used. We do not merely mean that people ought to be loving, but that love is what ethics is about. On this view, therefore, love is more than just a feeling. It is a normative principle of action circumscribed by the biblical admonition “love your neighbor as yourself.” In other words, we are to balance our self-interest with the interests of others. Ethical obligations are therefore those which arise from this norm in precise senses which vary according to the different love relationships we have, such as love of self, love of spouse, love of children or parents, love of friends, love of nation, or love of the needy, etc. Since these obligations arise from an aspectual norm, they extend over the entire spectrum of human experience and so also include obligations to nature, one’s work, one’s country, art, learning, etc. In short, the ethical aspect is the one whose order includes the norm and obligations of human love-life.

It should also be noted, however, that this ethical sense of love is not the same as the sense in which “love” is used by scripture for our proper relation to God. This is shown by the fact that the central commandment of love to God is not conditional as is the ethical command of love to our neighbor. For while the ethical love for others is to be balanced with self-love, the love of God is unconditional: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might” (Deut. 6:5; Mark 12:28-34). In its religious sense, therefore, the love of God is not mere ethical beneficence (important as that is), but is the commitment of one’s total being to the service of God above all else.

Finally, the term “fiduciary” is used to refer to the varying levels of reliability or trustworthiness a thing or person may have. This aspect is especially important in connection with human social relations of all sorts, which disintegrate rapidly where there is significant lack of trust. But because this aspect concerns all degrees of trustworthiness and certitude, it also has a special connection to religious faith. This connection arises whenever anyone trusts something as unconditionally reliable, for only something which has unconditioned existence could be unconditionally reliable. Trusting anything as unconditionally reliable therefore presupposes it to be what is self-existent and thus divine.

Even at this early stage, it is possible to see how a non-reductionist idea of such a cosmic law framework can free us from the horns of one of the old dilemmas which has plagued traditional theories of reality: the dilemma of objectivism versus subjectivism. This issue can best be understood as a controversy between contrary answers to the question: what is the source of the laws that give orderliness to creation? Whereas the objectivist locates the source of order in the objects of human experience, the subjectivist locates the order in the mind of the knowing subject. Of course, most theories have been partly objectivist and partly subjectivist, but to illustrate the two sides of the controversy I will use theories which are about as exclusively one or the other as any I can think of, namely, the theories of Aristotle and Kant.

For Aristotle, as we already saw, the “cause of the being of a thing” is its substance or form. A thing’s form is also responsible for determining the innate nature it shares with other things of the same type, and it is the nature of each type of things which programs them to behave and relate to other things in the ways they do. Therefore what we call laws of nature are our formulations of the observed behavior of things as caused by their internally fixed natures. This means that there really is no distinct law side to creation. “Law” is but our name for the regularities we observe in experience, and these regularities are guaranteed by the unobservable form for each type of thing. Thus the source of all regularity and order is located in the objects of experience even though that source is not itself directly experienced. On this view, humans come to know the orderliness of things by conforming their concepts to the natures of objects as they exist outside their minds; in other words, by conforming their thinking to “objective” reality.

Kant, on the other hand, maintained that the mind of the knower, or “subject,” is the source of all the order in experience. He held that what comes to our minds are chaotic sensory stimuli which the human mind then orders into an intelligible experience. His theory held that the human mind does this subconsciously and spontaneously in fixed ways it has no control over. So when we observe regularities in our experience, and when we attempt to formulate them into law statements, these are all conscious dealings with an orderliness we are already unconsciously imposing upon stimuli, thereby creating the reality we experience. So far as our conscious knowing is concerned, then, we are attempting to understand the objects we experience — just as Aristotle believed. But, said Kant, it is possible to do this only because those objects have first been formed by our minds imposing order on them. In this way the apparently objective order of reality is really subjective in origin.

It should be obvious that both objectivism and subjectivism are theistically unacceptable since each presupposes a variety of pagan religion by assigning to some part of the creation the role of being the independently existing lawgiver to the world. From the biblical point of view it is neither the known objects nor the knowing subjects which are the sources of the order of what we experience, but God alone who is the lawgiver to the world. Thus the theistic way of thinking about the laws of creation avoids the dilemma of objectivism and subjectivism by supplying a third alternative. Since scripture teaches that God created all the laws which govern creation, we may view the order of things as reducible neither to the objects known nor to knowing subjects. Instead, both objects and subjects are ordered and connected by being governed by the same divinely ordained law framework.7

Returning now to our clarification of the aspect list, we need to notice that just as its members are intended to reflect what we find in pre-theoretical experience, so, too, is the order in which they occur on the list. Reading from bottom to top, the order of their listing is intended to reflect the order in which properties of each aspect appear in things as we experience them prior to theorizing. That is, experience shows a sequence to the way things exhibit the aspects, such that properties of those lower on the list appear to be preconditions for the occurrence of properties of those higher on the list. For example, there are things which have physical properties without being alive but nothing living fails to have physical properties. So having physical properties appears to be a precondition for anything’s having biotic properties. Similarly, a biotically living thing may or may not be able to feel or perceive, but nothing capable of sensing is not biotically alive. In the same way, it appears that sensory perception is a precondition for a being’s ability to think in logical concepts, which is a precondition for being able to conceive of plans by which the historicalcultural formation of new objects from natural materials is accomplished. This ability, in turn, is the precondition for one of the most outstanding examples of cultural formative power: the invention of language, which is in turn a necessary precondition for the development of typically human social relations and customs. And so it goes on up the list.

Now I have been speaking of this order as one of pre-conditionality rather than of time, but this is not to deny there is a lot of evidence that the sequence just mentioned among aspects was mirrored in a real chronological development in the past. The evidence shows, for instance, that there was a period of time on earth when there were things that were quantitative, spatial, kinetic, and physical, but there were not yet living things; and there was a period when there were beings which were living but which did not feel or perceive, after which there were beings that were sensory but without logical thought, etc.

Nevertheless, this reflection of the aspectual order in time is not the same as the pre-conditionality I have been pointing to. Even without knowing about the gradual unfolding of these properties through time, the pre-conditionality sequence would still hold good for the reasons already given.

In fact, confusing pre-conditionality with the gradual appearance of properties in the past would prevent us from seeing that order with respect to the first four aspects, since we know of no objects in creation which ever lacked these. So we need to highlight the difference between the pre-conditionality sequence and the gradual appearance in time of the aspects higher on the list in the following way. We can say that a thing would have to be spatial for it to have movement, which is in turn a precondition for anything’s having physical properties. By the same token, there would have to be some amount or quantity of space, so that spatial properties have a quantitative pre-condition.8

But although the order of the aspect list reflects a pre-conditionality sequence in the way properties appear in things, this sequence cannot be used to support the weak reductionist strategy for a theory of reality. According to that strategy, the order we have been noticing is a causal one; some aspects — usually ones lower on the list — are said to cause the existence of the others which are higher on the list. That is, weak reductionism takes some kind(s) of properties and laws lower on the list to be not merely the pre-condition for the occurrence of the kinds listed higher, but the reason there are such higher kinds at all. But finding that properties of the higher aspects do not appear in things without those that are lower does not at all show that the lower ones produce the higher, since being a pre-condition for something is not the same as producing it. For instance, one of the pre-conditions for starting a wood fire is that oxygen be present, but the mere presence of oxygen will not start the fire. So we are entitled to notice here that proposing some lower aspect on the list as the reason why the higher ones exist is actually to make a pagan assumption. For to assume that it must be one or another of the aspects which cause the rest is to rule out in advance that there is a transcendent Creator who is both necessary and sufficient for the existence of them all — including their order of pre-conditionality.

Besides this religious objection, however, there are serious theoretical difficulties with any attempt to use the order among aspects as support for a weak reduction theory. We have already seen why the claim that any one aspect can cause the existence of the others fails when applied to its property side: it is self-performatively incoherent to abstract a kind of properties, regard its resulting isolation as real independence, and thus proclaim it to be the essential identity of things rather than just an aspect of them. But there is an additional reason why this claim is implausible when applied to an aspect’s law side. For while aspectual properties exhibit an order of appearance, aspectual laws do not. Explaining this point will at the same time allow a major part of the law framework theory to be presented, so it is worth pursuing here. But to make the point clear, I first need to introduce some new expressions that will allow me to speak in ways that will guard the distinction between the law and the property sides of any aspect.

The objects of experience (things, events, relations, states of affairs, persons, etc.) will be spoken of as existing or functioning “in an aspect” or “under the laws of an aspect.” In this way we will remind ourselves that the existence of creatures is always law-governed, and that we must always distinguish between the entities subjected to the laws and the laws which do the governing. So to say a thing “functions in” an aspect is another way of saying it has properties of that aspectual kind which are governed by that aspect’s laws. The law framework theory maintains that both the properties and laws of an aspect exist in mutual correlation. The law order of each aspect sets the limits for what properties are possible within that aspect and guarantees the necessary connections among them, but it does not create those properties. Neither is it the intrinsic natures of certain properties which set the orderliness for an aspect or bring other properties of that kind into existence. So while neither the law nor the property sides of an aspect exist apart from one another, neither produces the other; both depend for their existence on God.

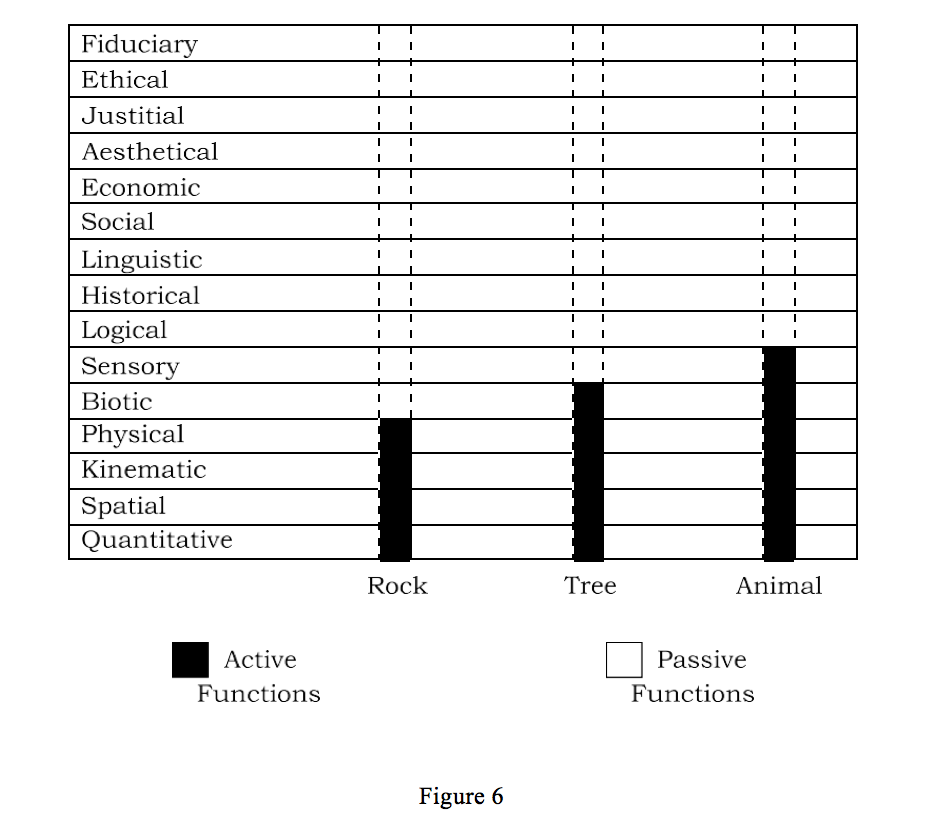

Focusing on this correlation now allows us to notice that there are two ways an object may possess properties of an aspect. I will speak of these two ways by saying that a thing may function in an aspect “actively,” or “passively.” The two functions are not, however, mutually exclusive. In fact, we contend that all things function passively in all aspects simultaneously, so that it is only the active functions in certain aspects that a thing may lack and which exhibit the sequential order of appearance noticed above.

Consider the example of a rock. According to the distinction being proposed, we would say that a rock functions actively in the quantitative, spatial, kinetic, and physical aspects. It bears these properties and is subjected to their laws such that it impinges actively on other things so far as these kinds of properties are concerned. The rock does not, however, function actively in other aspects such as the biotic, sensory, logical, economic, or justitial. Nevertheless, there is a real sense in which it does function in these aspects, because there are respects in which it is subjected to their laws. These respects depend, however, on the rock being acted upon by other things which do function actively in those aspects. So I will call the ways a thing is subjected to the laws of an aspect without functioning actively in it, its passive properties in that aspect. That the rock does not function actively in the biotic aspect means it is not alive. It does not carry on metabolic processes, ingest, or reproduce. But it can have properties which are indispensable to the life of living things and which are biotic in a passive way. As I said, these properties are passive in the sense that they are ways the rock can be acted upon, so these properties cannot appear except in relation to things having an active function in that aspect. The rock may, for instance, be part of an animal’s den; it may be the object on which a seagull drops clams so as to open them; if small enough, it may enter a bird’s gizzard and help grind its food. In other words it can have functions of being biotically appropriated by living things. In similar ways water and other nonliving things may display biotic passive functions without themselves being alive. Such properties remain only potential, of course, until something with a biotic active function actualizes them. But they are nevertheless real properties of those objects made possible by the fact that the objects are governed by biotic — as well as all other — laws. (Be sure not to confuse “active” with “actual” here. Passive properties can be either actual or potential, while active properties are always actual.)

A rock does not function actively in the sensory aspect either. This means that it does not feel or perceive. But the fact that it can be perceived by animals and humans who have sensory active functions is made possible (in part) because it is subject to sensory laws and has passive sensory properties. Remember in this connection that we do not directly perceive physical properties in the strictly sensory meaning of “perceive,” though we experience them in the wider sense of “experience.” Physical heat, for example, is defined as the rate of molecular vibration, but we do not sensorily feel a thing to he vibrating faster or slower when we feel heat. Again, physically speaking, light waves differ in frequency, but what we perceive is red or blue, not difference of frequency, etc.; and felt weight is the pressure or resistance we feel, while physical weight is gravitational attraction whether felt or not.

Similarly, the rock does not form logical concepts. But were it not subjected to logical laws it could not be a passive object of our logical thought. Just so, we could not value it economically were it not subjected to the economic law of supply and demand. Once again, these passive functions can only be actualized in relation to the active functions of other beings. The rock does not have actual economic value until someone values it. But were it not passively subject to the order of the economic aspect, it could not become an object of value for us. Its economic potential is a real characteristic it possesses, made possible by its subjection to an already existing economic order.

By contrast to a rock, a tree functions actively in the biotic aspect in addition to its active functions in the quantitative, spatial, kinetic, and physical aspects. It carries on metabolic processes, has a life span, is able to reproduce, and dies.

Its social function, on the other hand, is passive and is actualized only when, for example, it is used to provide shade for human social affairs. It may also have a passive aesthetic function if it is located or shaped so as to contribute to the aesthetic harmony of a garden. In contrast to the tree, an animal would also be said to have a sensory active function.9 Even the most primitive animals are sensitive in ways plants are not, if only at a crude level.

So far as we know, of all the creatures in the earthly cosmos, only humans have active functions in all the aspects.10

Perhaps the following diagram will help make this part of our theory clearer:

This distinction between active and passive properties allows us to appropriate the elements of truth from both objectivism and subjectivism while avoiding the extremes of each. We can agree with the subjectivist that things do not actually possess passive properties in an aspect apart from relating to humans who have an active function in it. (Although things have passive functions in relation to animals as well as humans, for the sake of simplicity here I’ll just speak of the ways they have them in relation to humans.) In relation to our perception, a rock’s passive sensory properties become actualized whereas apart from us they are merely potential. But because the rock’s subjection to sensory laws is independent of us, we can agree with the objectivist that we do not create its sensory properties wholesale. Nevertheless, we must disagree with the objectivist over whether these potentialities are to be located only in the rock. Instead we understand them as the result of the ways both the rock and humans conform to the distinct law side of creation. According to this distinction, then, we agree with the objectivist that it is false to say that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” or that economic value is entirely a human invention. Were it not that aesthetic and economic norms are already embedded in the cosmos, nothing could be experienced by us in those ways since there would be no economic or aesthetic potentialities for us to actualize. At the same time, however, it will still be true that such properties aren’t actually (fully) already present in objects independently of our activity in relation to them.

The distinction between active and passive properties also shows why we maintain emergence theories to be implausible where “emergence” is supposed to explain the existence of entire aspects.11 For while there is a sense in which active functions of things “emerge” in the sequential order discussed above, it makes no sense to suggest that entire aspects including their laws also emerged. The orderliness of both active and passive properties in each aspect is made possible by the laws of each aspect, so its laws would have to exist already. What sense does it make to suggest, for instance, that at one time there were only purely physical things but that logical laws then “emerged” along with logical properties? That would mean that the supposed emergence was not itself even logically possible! And what sense is there to such a claim when we notice that it is offering us a logical concept of a world supposed to be devoid of logical laws and properties? The same point applies equally to other nonphysical properties and laws. We could not, for example, have any notion of what a purely physical world would look like since it would have no sensory properties and thus no look at all! Nor could there be a plausible account of how living beings might have arisen and evolved if it is denied that there were already biotic laws making that possible.

In this way the active/passive distinction removes the most plausible objection to our contention that the aspects are all equally real. That point was earlier defended by applying the criterion of self-performative coherence via our thought experiment argument. The argument showed we cannot so much as form the idea of any aspect as really independent of the others. Against this, the objectionable sort of emergence theories have urged that the sequential order of their active functions is best understood as showing that the lower ones are causally basic to the higher ones because they are really independent of them. We have now seen why this is unconvincing, and so does not count against our first two guiding principles.12

Moreover, this point now puts us in a position to arrive at a third guiding principle for our theory. For if all creation is actively or passively governed by the entire law framework, we may now formulate the principle of aspectual universality: Every aspect is an aspect of all creatures since all creation exists and functions under all the laws of every aspect simultaneously.

This additional principle forms a complement to the principle of aspectual irreducibility and serves to emphasize two important points already mentioned:

(1) aspects are not to be confused with types or classes of things, but are kinds of properties and laws true of all things; (2) nothing we experience is ever experienced as purely a single (aspectual) kind of thing. This is important since so many of the entities proposed by theories of modern philosophy are precisely fictions of this sort. According to these theories, there are supposed to be purely physical objects, purely sensory percepts, purely logical concepts, etc. Compared with our experience, such entities are all clearly hypotheses; we never experience anything that has properties of only one or two of the aspects. And our critique of the reduction strategy has given us good reasons to reject such hypotheses in favor of what experience exhibits.

The last sentence should not be misunderstood to say that theories can never correct, enlarge upon, or even contradict particular features of ordinary experience. Saying that we never experience entities that are purely of one aspectual kind would not, by itself, have that consequence. But with respect to entire aspects, it does indeed say not only that experience displays a multiplicity of them, but that theories attempting to deny the reality of that multiplicity are either self-referentially, self-assumptively, or self-performatively incoherent. So we insist that the only plausible position is to say that all things and events function in all the aspects, provided passive properties are distinguished from active ones. The lesson, then, is that if a theory of reality is to explain the natures of the things we experience (and what else could a theory of reality explain?), it must take into account how they function in every aspect.13

I now want to introduce a more convenient way to speak of a point noted earlier. We briefly noticed that although experienced reality is multi-aspectual, various types of things display distinctive natures which are “more centrally characterized” by a particular aspect. I mentioned that the way things of a certain type function under the laws of a particular aspect can characterize their nature more strongly than the ways they function in the others, without involving any reduction among aspects. From now on, I will speak of this as the way things of a particular type are “qualified” by that aspect, and I will speak of the way entities are governed by the laws of their qualifying aspect as their “qualifying function.” This point can now help to explain the element of truth contained in the mistake of so many modern theories which regard reality as purely physical, or purely sensory, etc.

As examples of this mistake, recall what we saw in chapter 8 about how Mach and Einstein believed that the objects of our pre-theoretical experience are all purely sensory. Part of Einstein’s disagreement with Mach took the form of adding that there are also objects outside experience which are purely physcal. What is happening here, according to our theory, is that the qualifying functions of things are being mistaken for their exclusive nature. For exam-ple, we ordinarily think and speak of a rock as a physical thing, or of acts of perception as sensory perception, but these pre-theoretical intuitions of their natures do not show them to be exclusively physical or sensory. Our intuition of their natures focuses on the particular aspect which most centrally characterizes them, not which exhaustively characterizes them. So we take it that rocks have quantitative, spatial, kinetic, and physical properties actively, and passive properties in all the other aspects. Likewise, an act of perception is not only sensory; it can be counted, located, move, and use energy actively, while passively it can be trained, named, worth money, unjust, loving, or trustworthy. To illustrate the point further, consider the examples given earlier of other acts of human behavior. Human acts, we saw, are like all other events that occur in the world in that they have many aspects, and can differ according to their aspectual qualification: acts of buying or selling have an economic qualification, acts of eating have a biological qualification, acts of dancing have an aesthetical qualification, while acts of trying or deciding court cases have a justitial qualification. Even though such events are of distinct types, and each has a specific aspectual qualification, they still exist under the laws of all the aspects at once and can be studied from the standpoint of any of them. In fact, not only may they be studied from different angles corresponding to their other aspects, but it is impossible, as we have seen, for these other aspects not to enter into our concepts of them (think of the saltshaker example in chapter 4) and thus into the theories of any science no matter which particular aspect of them the science focuses on. So a corollary to our non-reductionist thesis is that no matter how hard a science may try to exclude from its account all properties but those of its delimiting aspect, it cannot avoid dealing with the properties its data display in other aspects.

So far the only argument given for this latter point was the experiment in thought which showed why we cannot frame the idea of any aspect or specific property in isolation from all others. But there is an additional argument for this same conclusion that is worth mentioning here, even though a full exposition of it is beyond the scope of this chapter. This argument has to do with the way basic concepts in every aspect exhibit a connection to those of other aspects so far as their meaning is concerned. Dooyeweerd refers to the way such concepts display this meaning connection by calling them “analogical concepts,” but that term should not be taken to suggest that the connection consists merely of similarities. In fact, it’s much stronger than that.

Take, for example, the way basic concepts in the non-spatial aspects include an element we originally derive from our intuitive experience of the spatial aspect. The original intuition of the focal meaning of that aspect has to do with extension in the simultaneity of all its points. But that idea is so interwoven into concepts arising in other aspects that they cannot be formed apart from it, nor can that focal idea be conceptualized apart from its inclusion in such nonspatial concepts. For instance, there is the concept of physical space which is not identical with the space of pure geometry; there is the biological concept of life-space; and there is the space of sensory perception which is not the same as that of mathematics or physics. We also speak of logical space as the “domain” of a quantifier or the extension of the reference of a term, and of justitial space as the limit of a juridical authority’s legal competency. Or look at the way our intuitive idea of life, originally derived from the biotic aspect of experience, figures in the concepts of other aspects. There is the psychological life of feeling, cultural life, and social life, each of which has added to it a distinctive qualification drawn from the original intuition of biotic life. Ditto for the life of the law, or the life of faith, etc. So far as our linguistic life is concerned, for example, anyone wishing to dispense with biotic analogies altogether would have to show not only that what is conveyed by the locution “a living language” or “a dead language” could be replaced without loss of meaning, but would have to do the same for “living together” as a socially qualified concept.

If it is objected that such analogical applications of the central metaproperty of one aspect to concepts arising in other aspects can be avoided provided we use enough ingenuity, the reply is simple: any circumlocutions that avoid one analogical application will inevitably use another. So our claim is not restricted to the assertion that a particular set of analogical concepts is unavoidable for a particular science (though there is good evidence that this is so), but that some analogical concepts or other are unavoidable since they are only able to be replaced by other analogical concepts.

Let’s consider just a few more examples of this point, this time drawn from the social aspect of experience since that is the one we will concentrate on in the next chapter. When we speak of social “life,” we draw on a biotic analogy, just as when we speak of “elements” of a society we draw on a numerical analogy. Similarly, treating certain beliefs or trends as “universal” in a society is to use a concept that draws on a spatial analogy, just as speaking of social dynamics or constancy appeals to kinetic analogies. Finally, the concept of a social cause employs a physical analogy. Surely no one can seriously contend that all such analogical concepts can be replaced with others that are not analogical!

This inclusion of ideas arising in one aspect within concepts indispensable to other aspects is made possible, we contend, by the same intense interaspectual connectedness that our experiment in thought pointed to. Analogical concepts are therefore yet another reflection of the ways each aspect is interwoven with all the others by tendrils of meaning consisting of the ways the properties of each appear in, and add additional qualifications to, concepts arising in other aspects.14 Thus the analogical concepts constitute the “internal” side of the inter-aspectual connectedness as distinguished from its external side that was defended with the thought experiment argument and which has been our focus up till now. That is to say, externally the connectedness between the aspects is shown by the way their properties are simultaneously exhibited by the objects of our experience, and by the way their irreducible reality cannot be coherently denied. To those points we now add that their internal connectedness is shown by the analogical elements found in certain basic concepts of every aspect — elements that cannot be eliminated without either resorting to other analogical concepts or eliminating the basic concepts themselves. (And, yes, this point was just made by applying the spatial analogy of internal and external to the inter-aspectual connectedness!)

The presence of analogical concepts in the sciences will now be taken in conjunction with the experiment in thought argument to have demonstrated the basis for yet another guiding principle for the law-framework theory. I will call this the principle of aspectual inseparability. This means that aspects cannot be isolated from one another since their very intelligibility depends on their connectedness. Though they may be abstracted from the things and events which exhibit them, they cannot — even in thought — be isolated from one another.

The arguments now given for the principle of aspectual inseparability serve, however, as a reminder that the issue of their connectedness was the focal point of our case for the religious control of theories. So it is also incumbent on the law framework theory to say what explains that connectedness. To do that, I want now to revert to the metaphor of a necklace that I used to explain what traditional theories of reality were up to. And I also want to remind you that earlier I said that the law framework theory not only would offer distinctive answers to traditional philosophical questions, but would also recast many of those questions. So the first item to be explained is to say why the necklace metaphor, though accurate to the history of Western philosophy, is nevertheless objectionable from our standpoint. As should be clear by now, our position is that no aspect of experience is to be thought of as separable from the rest or as produced by any of the others. So instead of a necklace comprised of separable beads connected by a string, the metaphor more appropriate to the law framework theory would be a necklace made up of tightly interwoven continuous strands. In fact, we would have to add that the strands are not only wound around one another, but that fibers from each strand are interlaced throughout all the other strands. To press the figure still further: not only can’t the necklace exist apart from its strands, but the strands can’t exist apart from being woven into the necklace, and none of them produces any others. All alike are produced, interwoven, and sustained by God. Thus the inter-aspectual connectedness displayed by things, and their deepest unity and identity as individual realities, are incapable of being abstracted or of being explained by any of their aspects. Logical identity, for example, is not the most basic unity of a thing, but is instead only one aspect of a thing’s individual unity — an aspect which itself depends upon the deeper inter-aspectual connectedness that is supplied by God and is incapable of analysis or further explanation.

While this means that the most important part of our position on the interaspectual connectedness is its transcendent Origin, it doesn’t rule out that the strands of the necklace exhibit a common denominator within our experience. It’s simply that on this view, in contrast to pagan theories, what the strands all have in common is not the same as what produces them or combines them into distinct, unified individuals. So while our theory does not take any aspect(s) to be the basis for the existence of all others, it does propose a feature of creation as the common denominator of all aspects. That feature, we say, is time. Not only are the things, events, states of affairs, relations, persons, etc., that populate the created cosmos temporal, but so are the kinds of properties they possess and the laws that hold for them. In fact, a non-reductionist view of time requires us to say that the law order of every aspect exhibits a beforeand-after character so that each is a distinct sense of temporal order. There is, e.g., the before and after of lesser numbers and greater ones in math, of energy causes to effects in physics, of sensation to feeling in psychology, of premises to conclusion in logic, and so on. So while it is a fundamental characteristic of the existence of creaturely entities to endure in time, they always do so in accordance with the many (aspectual) kinds of order which are also the order of time. Thus the law side of the aspects constitutes the various senses of temporal order, no one of which is any more really what time is than any other.

I hope it is clear that by identifying the common denominator of the aspects as time, there is no danger of re-introducing the idea that something about the cosmos is divine. Time is not a substance, and it would be preposterous to regard time as an agent; it causes nothing. By contrast to pagan theories, the law framework theory insists on a mutual interdependence between entities which are the factual side of time, and the laws of creation that constitute the order side of time. Neither entities, properties, laws, nor time exist apart from one another, but none is the cause of the existence of the other. They are all creations of, and are sustained by, God whose (unaccommodated) being is both super-temporal and above all laws.

I trust it is also clear that the guiding principles formulated above will not now be used as premises from which to deduce hypotheses for our theory, but will instead regulate our theorizing in the way we’ve noticed divinity beliefs regulate theories generally. So we will take it as a sign that our theorizing has gone astray if any hypothesis it postulates leads us to: (1) deny the distinctness and irreducibility of a multiplicity of aspects to our experience, (2) restrict the range of any aspect within the created cosmos, or (3) regard any rupture of the continuity and interdependence of the aspects as complete or real rather than as partial and an artificial product of high abstraction.

At this point students have often asked me whether these principles couldn’t be accepted quite apart from belief in God. They have found them highly attractive compared with the long parade of reductionisms that have populated Western philosophy, but have worried about whether accepting them would entail belief in God. So they expressed the hope that they could accept the principles without belief in God, in which case there would be no necessary connection between religious presuppositions and theories after all! To this I have always replied that the connection is not that the two are equivalent. For while belief in God requires non-reduction, non-reduction does not entail belief in God. This is because it is logically possible for someone to take the position that whatever connects the aspects is some unknowable X rather than God, and reject reduction on that ground. Of course, that will still amount to belief in a transcendent divinity, it just wouldn’t be the God whose covenant dealings with humans is recorded in the Bible.

But I have also then added that while such an alternative is logically possible, existentially it is not a genuine option for real humans. By this I mean that the reason it fails to be a live option is not to be found in a theoretical argument, but in the religious nature of human beings. For while anyone may try to view all aspects as equally real and mutually irreducible on the ground that whatever they all depend upon transcends them but is totally unknown, it is not possible for anyone to be satisfied with such an unknown X for long. Given the innate religious disposition of the human heart, something satisfying some minimal description will be experienced as divine. And unless the electrical charge of that disposition to faith comes to ground in a specified divinity outside creation, it will at last come down on something within creation and will demand that the rest of the cosmos be reduced to whatever that is.

11.4 THE NATURES OF THINGS

A. Natural Things

Let us now return to the issue of the experienced differences in the natures of things and, starting with natural things as distinguished from artifacts, see if we can give an account of them which conforms to our guiding principles. We already admitted that our pre-theoretical idea of a thing recognizes some specific aspect as more “centrally characterizing” of its nature. We explained this by the concept of what it means for a thing to be “qualified by” an aspect. This may now be further clarified as follows: the qualifying aspect of a thing is the aspect whose laws regulate the internal organization of the thing taken as a whole. So our explanation of such pre-theoretical intuitions is that they correspond to the aspects whose laws exercise the overriding governance of the internal organization of the things we call “physical,” “living,” “sensory,” “logical,” etc. Such pre-theoretical classifications never intend to say that those things are exclusively physical, biotic, or whatnot, or that the properties and laws of any of those aspects cause the other aspectual kinds of properties and laws displayed by the things classified in those ways.

Let us now look more closely at what is meant by saying that the laws of a thing’s qualifying aspect exercise an overriding governance of the thing taken as a whole. If we consider the quantitative, spatial, or physical aspects of a tree, for example, we see that they do not tell us about the aspectual characterization which is nearest to our pre-theoretical idea of its nature. But when we come to the biological aspect of the tree, we have reached that aspect whose laws guide the internal organization and development of the tree as a whole. It is the biological laws which direct or lead the overall arrangement of its parts, its internal relations, its processes, and the structural arrangement among the properties of them all. This is why it comports with our pre-theoretical idea of its nature to say that it is qualified as a living thing. And it is what we mean by saying that its nature is “more centrally” characterized by its biotic aspect than by its spatial or physical aspects. Moreover, this part of our account fits well with the previous distinction drawn between active and passive functions of things. That distinction recognized a sequential order of pre-conditionality among aspects so far as the appearance of active functions in things is concerned. It is significant, then, that for every example we can think of, the qualifying aspect of a thing is also the last aspect in that order (the highest on our list) in which the thing functions actively. For instance, a rock is qualified by the physical aspect which is the highest on the list in which it functions actively. The fact that it is merely passive in the remaining aspects is partly why we intuitively see a rock as having a (centrally) physical nature. By contrast, the qualifying function of a plant is its biotic function since it is the biological laws which exercise overriding governance of the internal organization and processes of a plant. Here again, it is also the biological aspect which is the highest aspect on the list in which a plant functions actively. Thus there appears a striking correspondence between our intuitive grasp of a thing’s highest active function and its qualifying function as defined by the law framework theory.

Now it would take more space than I have here to demonstrate this correspondence for hundreds more examples. But since this has already been done elsewhere,15 and because of the lack of convincing counterexamples, our theory now proposes to accept this correspondence as part of our concept of the qualifying function of a thing. Therefore, the fuller definition of a thing’s qualifying function will be: that aspect whose laws govern the overriding internal structure and development of a thing considered as a whole, and which is the highest in the sequential order of aspects in which the thing functions actively. This deliberately includes both the pre-theoretical intuitive recognition of a thing’s nature as centered in the last aspect in which it functions actively, and the theoretical reasons for identifying which kind of laws have overriding governance of the internal structure of a thing taken as a whole. But please notice that the correspondence between the aspect we intuitively see as qualifying a thing’s nature and the kind of laws that govern its structure taken as a whole, is not now simply being stipulated by this theory. It is instead a prediction of the theory, and is subject to confirmation or disconfirmation by philosophical and scientific analysis of various types of things and events — so long as the analysis itself follows our nonreductionist principles. Thus the concept of the qualifying function of things provides a way to account for their natures which is at once both thoroughly nonreductionist and subject to empirical confirmation. What has been said so far about the concept of a qualifying function and the distinction between active and passive functions is, however, only the start of a nonreductionist account of the natures of things since it is not yet specific enough. In saying that a tree’s qualifying function is biological, our theory has not yet accounted for anything unique to a tree as distinct from other types of plants. Since the natures of things have been only roughly approximated when we identify their qualifying functions, we need greater specificity if we are to account for the differences in nature of various types of things having the same qualifying function.

The way in which our law framework theory can be enlarged to cover this lack refers back to the sequence in the appearance of aspectual active functions discussed earlier. For the fact that there is order among aspects implies the existence of inter-aspectual laws in addition to those which hold within aspects. The laws of this inter-aspectual order I will call “type laws.” These laws range across aspects regulating just how properties of the various aspectual kinds can combine so as to form things and events of specific types.16

The concept of a type law can now supplement the concept of the qualification of a thing so as to give a more adequate account of the nature of the type to which a thing belongs. For example, the fact that a tree is biologically qualified can now be coupled with the distinctive structural organization of its parts and functions which make it a tree rather than a mushroom or a daisy. (Of course, just what structurings these laws allow cannot be predicted in advance; their discovery depends on empirical analysis of the realities we find.) Thus our law framework theory proposes a complex, crosshatching network of laws. In addition to the causal relations we experience daily, the network includes aspectual laws which determine the necessary relations among properties within particular aspects, and type laws which govern the structural combinations among properties of different aspects that make possible the myriad of specific types of things and events in the cosmos. It is this crosshatching governance by the latter two sorts of laws by which our theory accounts for the nature of a type of things. That is, our understanding of a thing’s qualifying function, taken together with an analysis of its structural type, comprises the account our theory gives for our pre-theoretical idea of the nature of a thing. (A more complete account of the significance of the idea of type laws, as well as of the other principles and concepts introduced by this theory, will be given in the next chapter.)

With this sketch of the law framework we are now in a position to recognize an important feature of our theory that is implied by what has been said so far, but which has not yet been made explicit. It is a feature by which it departs from the majority of reductionist theories — including those adapted by most theistic thinkers. And though I can only briefly allude to it here, even a short statement of it will serve to bring into greater clarity the theory’s unique direction, that is to say, how and why its theistic presupposition drives its development along certain lines to the exclusion of others.

The feature I am referring to is that this theory gives us a way to account for the natures of things without needing the idea that things have a “substance.” The direction of thought away from this concept took its impetus from the biblical idea that nothing in creation exists independently, and from our proof that no independence claim for any aspect can be justified. Hence there is nothing in creatures which causes them to be what they are. It is God who causes them to be what they are. The most basic characteristic of all created realities, then, is to depend on God in every respect. As a consequence, our theory of the nature of created things or events has no place for the concept of substance, but sees a thing as an individual structural assemblage of properties determined by a type law and centrally qualified by whichever aspectual laws regulate its internal organization.17 It is because no aspect of any created thing is to be viewed as its substance — that on which all its other aspects depend — that we contend it is a mistake to think of a thing or event as anything over and above an individual law-structured combination of all the properties comprising it. This is a further consequence of our rejection of the reductionist program of selecting one or two aspectual kinds of properties as what things are, leaving the rest as what things merely possess (or denying them altogether). So we reject the idea that there is any substance to a thing which underlies and causes the rest of its properties. Instead, we hold that a thing is an individual combination of properties of every aspectual kind, structured by laws within the cosmic law framework that determine the type of thing it is.18

B. Artifacts

So far I have applied the concepts introduced by the law framework theory only to natural things. We started with them because the natures of artifacts are more complicated than can be accounted for only by the qualifying function of their natural material. Nor can that deficiency be remedied simply by adding the type law for their natural material to the account. This is because the structural arrangement of properties which typifies the things serving as natural material will never tell us about what is new in the nature of an artifact — about what its natural material has become. So whether the artifact is the product of humans or animals, we need to expand our concept of the nature of a thing beyond its qualifying function so that we can account for the new nature possessed by an artifact that was not possessed by its natural materials.

For example, the earth or rock which lines an animal’s den or hole would, by itself, have no more than a physical qualification. But once it has undergone transformation in order to meet an animal’s biotic or sensory needs, it acquires an additional qualification despite the fact that it has only a passive function in the biotic or sensory aspects. Unless we recognize that such transformation has occurred, we would not recognize the earth or rock as the den of an animal and so we would miss what it has become. Thus, our concept of the nature of such a thing needs to be expanded to include the aspect qualifying the process of transformation which produced it. Thus it will be necessary for our theory to subdivide the aspectual qualification of an animal artifact between at least two aspects. We will call the aspect in which the natural material of such an artifact has its highest active function its “foundational function,” and we will call the aspect whose laws governed the process of its formation, its “leading function.”

So when a beaver constructs a lodge out of mud, sticks and other materials, those materials have only physical or biological qualifying functions in their natural state. But as an artifact, the lodge has acquired an additional sensory qualification because the beaver’s activity is governed by its sensory instincts and needs (shelter, warmth, protection of young, etc.). Thus we will say that the lodge is qualified by a physical or biotic foundational function while the process of its formation was led by sensory feelings and needs. We will therefore speak of the lodge as having a sensory “leading function.” This means that artifacts differ from natural things because part of what qualifies them (their leading function) is an actualized passive function rather than an active function as it is in the case of natural things.