Reading: Chapter 12 - A NON-REDUCTIONIST THEORY OF SOCIETY

Chapter 12 - A NON-REDUCTIONIST THEORY OF SOCIETY

Dr. Roy A. Clouser

12.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter will begin by defining some basic terms so they can be used to develop a law framework interpretation of social theory. Before doing that, however, it is necessary to point out that the approach taken to this task will be to start by recognizing a specifically social aspect of experience, which is not the usual way social theories are constructed. Most theories simply confine themselves to specific organizations or problems, rather than setting such issues in the broader context of the distinctly social aspect of human experience. This aspect is the one that includes such properties as prestige, status, respect, and authority, and norms such as those that concern politeness and deference to the elderly. In this connection, please keep in mind the point made earlier about each aspect being known by direct, intuitive, experience rather than by definition or inference. As with the other aspects, no definition of the distinctly social side of human experience could convey what is meant to anyone not already aware of it.

It is from the angle of this narrower-than-usual sense of “social” that the relationships theorized about in this chapter will be viewed. So our approach starts with the ways the norms of this aspect, in interaction with those of other aspects, make possible the specific ways such interactions get organized. In particular I will focus on the relation of authority, and approach the various ways humans organize their social life by examining the specific types of authority that are embedded in those organizations. So while “social” could simply mean anything done by two or more people, I will be concentrating here on the social relation of authority as it arises in organized social life. And I will be applying the law framework theory to that relation to see what insights it can supply for determining the right way to interpret the various types of authority as they are exercised in social organizations.

The first term in need of clarity is, of course, “society.” As I use it, this term will refer to individual persons and/or groups of persons standing in any one of three basic social relations: individual to group, group to group, and individual to individual. In keeping with the remarks of the previous paragraphs, the term “group” is used here to mean a durable one which joins its members into a recognizable unit, rather than a chance collection of people such as those who happen to be waiting for a bus. But since the term “group” is so vague, from now on I will use the term “community” for a durable social unit.1 Also in keeping with the previous paragraph, I will confine the discussion to the first two of these three relations, since those are the ones that concern social organizations. Doing this will pave the way for a law framework understanding of the state to be sketched in the next chapter.

Social communities will be regarded as falling into two major divisions which I will call “institutions” and “organizations.” Only the strongest sort of social community will be called an institution, so this use of the term will refer only to communities having all of the following three characteristics: (1) their members are united to an intensive degree; (2) membership carries the intention of being life-long; (3) membership is (at least partly) independent of the member’s will. The communities with these characteristics are marriage, family, state, and religious communities such as a temple, mosque, or church.2 Membership in institutions can be independent of a member’s will in two senses. One is that a person is usually born into a family, a state, and some religious affiliation. The other is that changing membership in such institutions is not done easily, or simply by unilaterally deciding to do so. To change one’s citizenship or one’s membership in a religious institution requires being accepted by the new institution involved, and legally ending a marriage involves the divorce being recognized by the state. And no matter how the bonds of familial affection may break down, one is a biological member of one’s family so long as it exists. By contrast, social “organizations” are ones in which the member’s bond is less intense and less permanent. Organizations also decide who may or may not join them, but membership does not usually carry the intention that it be life-long, and their members are free to come and go more easily. Examples of organizations are businesses, hospitals, labor unions, political parties, and schools.

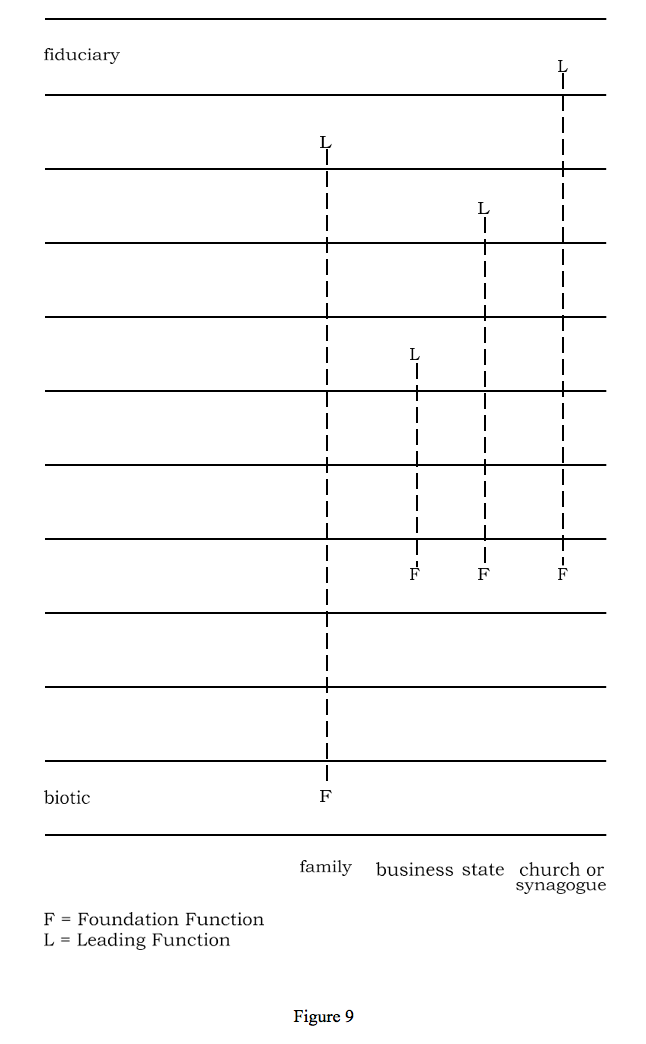

In the last chapter we saw why our theory regards artifacts as having natures that are centrally characterized by two aspects: their “foundational function” is the aspect that qualifies the kind of process by which they’re formed, and their “leading function” is the aspect that qualifies the kind of plan that leads their formation. So far as the former is concerned, I said, the process by which most artifacts come to be formed is qualified historically. (Keep in mind that as we used the term “historical” it was equivalent to “cultural,” and referred to the free exercise of the technical power humans have to form new things from natural materials.) We then noticed that social communities are also among the new things humans form, and that most of these also have a historical/cultural foundational function.

But there are important differences between artifacts that are things and artifacts that are social communities. For example, the leading functions of the former are qualified by aspects in which they function only passively. A chair or a house has a social leading function, but it doesn’t carry on social relationships actively but has only a potential social passive function in that aspect. So its leading function needs to be actualized in relation to human social life. Social communities, by contrast, do function actively in all aspects as well as have a leading function in some one aspect. A business, for instance, carries on economic activity, just as a band or dance troupe performs aesthetically qualified actions, or a church actively conducts rites having a fiduciary leading function. So when I said earlier that only humans function actively in every aspect, that should now be understood to include communities made up of humans not just individual humans.

Despite being like individual humans by having active functions in every aspect, however, social communities differ from individual humans by having natures that can be explicated by the relation of their foundational and leading functions. We have already seen why it must be held that human nature has no qualifying function, and further arguments for this point will shortly be given. For now, it will be sufficient to recall the reason we’ve already noticed, namely, that while the human heart exists and functions under the limits of aspectual laws, it is not determined by them but possesses genuine freedom. This freedom, I said, is possible because there is more to the heart than its aspectual functions, and this “more” reflects its having been created in the image of God. What qualifies human nature is therefore not any one aspect of creation nor is it all of them taken together. Human nature is at its core religious: humans were created for fellowship with God, have a relation to God as the most central characteristic of their nature, and have their ultimate destination with God outside the present cosmos altogether. So although human social communities are like individual humans in having active functions in all aspects, they do not have natures characterized by the three religious relations just mentioned. Instead, they are like other artifacts in having a nature that can be understood by the relation of their foundational to their leading functions in conjunction with their type law. For social communities, then, we will continue to speak of their foundational function as the aspect that qualifies the process of their formation, and their leading function as the aspect that qualifies the kind of plan which leads their formation.

At this point you might wonder why I said that “most” social communities have a historical foundational function; after all, what else could possibly qualify the process of their formation? The answer is that the “most” was intended to leave room for two social institutions that are not simply the free creations of human planning and formation but are rooted in the biotic, sexual, side of human nature. These are marriage and the family. The specific social forms for establishing marriages and families are, of course, under human control and vary culturally. But it is the underlying differences between the sexes and the attraction between them which qualifies the process by which marriages and families are formed. And that is not itself a product of human planning or invention. Perhaps the best way to see the centrality of the biotic aspect to these two communities is to notice the fact that they are the only ones that cease to exist when their original members die. A marriage ceases to exist whenever either spouse dies, while a nuclear family ceases to exist if either the parents or the children die (sib relations may of course remain after the death of parents, but the family does not). This is sufficient to distinguish these communities from others such as churches, schools, businesses, charitable organizations, states, etc., that can continue to exist even when all their original members have left them or died. Our theory will therefore call marriage and family “natural institutions”, in order to recognize their biotic foundational function.3

At the same time, however, any view of marriage or family which sees them as restrictively biological is reductionist. While the biological order of creation provides the foundation of their formation, their leading function and structural purpose is ruled by the ethical norm of love. Here our theory not only appeals to its three guiding principles, but combines them with the teaching of scripture about marriage in which it is spoken of as essentially a community of love between husband and wife (Gen. 1:28, 2:18, 24; Mark 10: 5-9; Eph. 5:25- 33). In addition, the book of Genesis further evinces this view by the way it looks upon the sexual relation of Adam and Eve as necessary to their love bond and as good for both of them prior to their fall into sin. And finally, our ordinary language reflects this as well when we speak of humans not merely as “mating,” but as “making love.” Thus, anyone who insists, as Aristotle did, that the sole purpose of sex is to perpetuate the species has made a serious mistake. No doubt marriage and family do accomplish the purpose of perpetuating the human race. That fact does not, however, alter what we called the “structural purpose” of any artifact, which is ruled by its leading function. Please keep in mind what was already pointed out about an artifact’s structural purpose when that was distinguished from other subjective purposes people may have in connection with them. For while it is true that partners to a marriage may be motivated by social climbing or financial gain, the structural purpose of the marriage institution remains unaffected. It is guaranteed by its leading function and is exhibited only by its inner spirit: the perpetuation and enhancement of the sort of love which forms the closest of all human ties.4

In addition to their foundational and leading functions, all communities are structured by a type law and each type exhibits a number of varieties. There are varieties of states, businesses, and artistic communities, for example, and there are also varieties of families. Often the familial variations are connected with how the family’s living is supplied. Consider, for instance, the variation in the relations among the members of a farming family, a laboring family, a royal family, and a family which runs its own business. We also recognize that just as there can be deformed natural things, there can be deformed social communities as well. Two examples are a state which is an absolute dictatorship and a polyandrous family. But neither the varieties nor the deformities in actual social communities affect the structural principles which make them possible, since these principles reside in the law side of creation. So while actual communities can be deformed, the qualifying functions and type laws which structure them are immune from alteration.

This sort of approach to social theory is not at all well received these days. Many theorists wish to regard all social relationships as wholly human inventions and therefore as infinitely variable rather than as the actualizations of potentialities made possible by type laws already extant in the cosmos. But calling attention to the aspectual and inter-aspectual laws of creation is one of the main interpretive advantages our theory can provide. It allows us to focus on the fixed principles which underlie the differing types of human social communities, so that we are not led astray by every variation or deformation they may have. That is a major advantage afforded by understanding them in terms of their aspectual qualification (their foundational function plus their leading function), and their specific type law. Discovering the latter is achieved by analyzing the most basic ways the members of a community must relate in all the aspects in order for that type of community to exist. It is by formulating a general statement of these relations, that we can approximate the type law which makes them possible. But without an idea of the law framework of creation to guide a theory of social communities, how could one hope to arrive at the aspectual nature of each type? How could one ever tell which social forms are normal and which are aberrations? As Dooyeweerd has put it:

If we consider a beautiful embroidery from behind, we do not discover any pattern in the confused criss-cross of the interlacements. Similarly, we cannot discover the structural patterns of the different types of societal relationships if we pay attention only to the . . . [forms we actually find in existence and the ways] in which they are interlaced with one another. (New Critique, vol. III, p. 176)

But, it may be objected, does this mean that we cannot do sociology without a philosophical theory? If so, is the science of sociology then collapsed to social philosophy? And if not, what is the difference between them?

We have already seen the reasons why no theory devoted to a particular aspect of experience can avoid philosophical presuppositions. All alike will make assumptions about the nature of reality and knowledge, whether they spell them out or leave them unarticulated. So pointing out how our theory of reality regulates sociology is not doing anything more than making explicit how the law framework view of the nature of the cosmos can guide social theory. Taking this approach is therefore no more a demand that all social theorists do philosophy first than it would be to demand that of any other science. Whereas philosophy explicitly deals with how all the aspects relate to one another, scientists (sociologists included) may presuppose some such idea without making it explicit. But whether it’s made explicit or not, in every case, the theories offered will vary relative to how they understand the inter-aspectual connectedness. Leaving the law framework theory merely implicit in this chapter, however, would defeat its very purpose since what I’m up to here is not only to show the differences that theory makes to sociology, but to elaborate the law framework theory in the course of doing so.

In applying the law framework theory to social organizations we are not, however, restricted to employing the concepts of qualifying functions and type laws — powerful as those are. We also have at our disposal aspectual norms as the standards for what is normal or abnormal about various communities. This is a highly controversial issue. Many social theories claim that no account of society can be scientific unless it deletes every reference to norms. So we now turn to the question as to whether sociology can develop a theory of the natures and interactions of communities simply by describing them as they are (the social facts), without any reference to how they should be (social norms). To treat this issue, the first matter we must be clear about is the meaning of the term “norm.”

12.2 FACT VERSUS NORM

In the last chapter we noticed that there is a sequence among aspects with respect to the way things have active functions in them. Active functions in aspects lower on the list are preconditions for things to have active functions in aspects higher on the list. Another difference we may now notice between the aspects which are lower on the list and those which are higher is that the laws of the lower aspects are rigid; they are laws that we cannot disobey even if we try. There is no way we can actually violate the law order found in the quantitative, spatial, kinetic, or physical aspects. But from the biological aspect upward on the list, the character of that order changes; the higher we go on the list, the more of each aspect’s order can possibly be disobeyed. Rather than only being an order that rigidly determines what is necessary, possible, and impossible, the order within the aspects above the physical is increasingly made up of norms which are guides for the ways in which plants, animals, and humans need or ought to act if they are to maximize purposes qualified by those aspects.

For example, the laws of the biotic aspect determine the relations among certain biological properties. But there are also biotic norms for health which relate other biological properties. A living thing may violate such a norm and still live, but it will be healthier if it conforms to the norm. Or again, think of the laws of logic. There is a sense in which logical laws are inviolable. Everything in creation exists in conformity to the logical axiom that nothing about it can be both true and false in the same sense at the same time. But we can disobey this axiom in our thinking by committing logical fallacies of reasoning or by holding incompatible beliefs. Thus, while the logical order for creation has the character of inviolable law for everything other than thought, it is normative for our thinking. We can disobey it, but we ought not to do so if we want any logical assurance we have made a valid inference or that our beliefs are consistent. For aspects even higher on the list, our ability to disobey their order extends beyond our thought to our behavior. We may disobey economic, aesthetic, justitial, ethical, and other norms in action as well as in thought or belief. But the affects of doing so will always undermine the purposes of increasing wealth, creating art, achieving justice, or doing good, etc., unless these affects are altered by intervening forces. Our being able to disobey norms does not, however, detract from their reality as parts of the cosmic law framework. Indeed, it is often the consequences of disobeying norms that display most vividly their reality and binding character. To sum up: it is because these parts of the law framework have the distinctive character of being able to be disobeyed by humans, and because they provide the standards for what ought to be, that they are called “norms.”

Having now indicated what a norm is, I want to warn against several common misunderstandings about them. First, it is important not to confuse what is average or usual with what is normal in the sense of conforming to an aspectual norm; “normal” as I’m using it means that which is in accordance with an aspectual norm no matter how often it may be disobeyed in practice. Second, the governance of these norms within their aspect does not depend on our consciously knowing precise statements of them, or upon our deliberately trying to conform to them. People are often governed in their thought and behavior by norms which they have not consciously articulated. This is demonstrated by the fact that people recognize certain activities as conforming to norms while other activities do not, even if they cannot say exactly what those norms are. The most obvious example is the way people who have never formulated the law of non-contradiction still try to avoid contradicting themselves. And although we may not be able to state many norms of art or do so with precision, yet we make such judgments as “This work of art is better than that one.” Keep in mind, too, that until relatively recently no one had formulated norms for psychology or economics, so the fact that norms have not yet been formulated for a particular aspect doesn’t show it can never be done. Similarly, in linguistics we recognize that a particular string of words is nonsense rather than a sentence, or that one way of stating something is clearer than another, whether or not we can formulate normative linguistic rules for clarity. These examples show that we always presuppose norms for these aspects, even though they may remain vague, unformulated, or even sub-conscious.

Finally, a norm is not an absolute perfection as was the pagan Greek idea of a Form. It should not be thought of as a changeless and perfect model for language, business, justice, morality, or whatnot. If it were, then everything would have to copy it exactly to conform to it, and all the things which conformed to it would be exactly alike. Rather, we see a norm is that part of an aspect’s order which serves as a rule for guarding the values qualified by that aspect. For this reason many actions, thoughts, and artifacts may all equally conform to the norm of an aspect and yet be quite different from one another. For example, performances of a symphony may differ and still be equally aesthetically excellent, different statements may be equally ethically compassionate, and different judgments or actions be equally just.5

All that has just been said about norms was preparatory to addressing a number of problems for sociology which center around them, especially as to whether they are subjective or objective and whether they can or should be dispensed with in social theory. The subjectivist view is that there are no norms in reality, but merely the subjective feelings and biases which individuals and societies posit as (arbitrary) guides to behavior. So subjectivists see the inclusion of norms in any social theory as unscientific. The chief argument in favor of this position is that there are serious disagreements over exactly what the norms are, and no clear-cut way to settle the disagreements. From this the subjectivist draws the conclusion that norms cannot be objectively real, so that sociology must stick only to descriptions of the social facts (what “is”), and eschew all normative evaluation (what “ought to be”). Among those who take this approach, however, there is also disagreement about just what the sociological “bare facts” are, once all normative judgments are supposedly stripped away.

In the classical objectivist theory of Aristotle, on the other hand, norms do have a basis in reality. This basis is thought to be the same as the basis for the laws of the “natural” aspects: both law and norm statements result from our formulations of the nature of things as guaranteed by their Form. Although not all objectivist views of norms are committed to Aristotle’s theory of Forms, all are committed to saying that there is an important sense in which norms can be directly “read” from nature. They then supply arguments to defend their particular reading of what those norms are, and to show that it is not really possible to exclude all normative judgments from social theory.

As in the case of our theory of reality, the idea of a cosmic law framework gives us a distinctive direction of thought which steers a course different from both subjectivism and objectivism. Since we hold that all things in creation function under all aspectual laws alike including the normative aspects, we utterly reject the position that norms of logic, linguistics, economics, art, justice, ethics, etc., are nothing more than subjective biases. Though people do disagree over exact statements of the norms of some aspects, there is no way anyone can avoid the general recognition that human acts and social communities are norm-governed in their very nature. For example, the employment of norms of clarity in language or of supply and demand in economics are unavoidable in speech and business; so is the ethical norm of love (love your neighbor as yourself) for doing what is morally right, or the norm of justice (that people should get what they deserve) for being fair. These norms are principles that rule the leading functions that make these kinds of human activities and communities possible even when people engaged in those activities or communities deny and/or disobey them.

This fact cannot help but be implicitly recognized, even by a theory that explicitly wishes to deny it. The purpose of a business organization, for instance, cannot help but be led by economic norms even if the subjective intention of its owner is not economic wealth but fame or besting a personal rival. Similarly, the purpose of the marriage institution is still led by norms of love even if one of the partners has married only for economic gain. This is why when there is no love between husband and wife there is no real marriage, and we say they have a marriage “in name only.” Likewise, the members of a family may in fact hate one another rather than conform to the ethical norm of love. But in that case, everyone recognizes that it is an ab-normal family. Or, again, the purpose embedded in the leading function of a synagogue or church is governed by fiduciary norms of faith even if some of their members participate in them purely for social prestige. This is why we maintain that there is a purpose ruled by the norms of the leading function of human acts and artifacts which is unavoidably embedded in their nature. Were these norm-governed structural purposes truly eliminated from our view, we would cease to recognize the actions or communities from which they’d been deleted as distinctively human, and the greater part of what they are would be lost to our understanding. What, for instance, would be left of our understanding of a business if every reference to economic norms were eliminated? What would be left of our understanding of marriage or family if all reference to love were excised? What would be left of our understanding of a temple, synagogue, church, or mosque if we ignored the norms and purposes of faith? The very concepts of these communities would be stripped of their most essential characteristics!

One interesting consequence of the concept of structural purposes embedded in the leading functions of communities is that it allows our theory to make sense of criminal activities and communities in a way many other theories cannot. A criminal syndicate, for instance, is still structured by economic norms that lead its economic purpose, even though the conduct of its business deliberately disobeys the norms of justice reflected in legal statutes. In fact, no organization can even be recognized as criminal unless the norm of justice has been invoked to make that judgment. Similarly, if we try to explain the rate of crime in terms of poor housing, poverty, and other such factors, these conditions can only be recognized for what they are by the way they violate social and economic norms. To call housing “poor” or an economic condition “poverty” is to make a normative judgment.

The same holds true for other social institutions and organizations as well. A state may act illegally, but it will still have a legal structural purpose led by the norm of justice. This is why the crimes of a government or government officials seem the more reprehensible to us: they violate the very purpose that is qualified by the leading function of that institution. The same is true of a political party whose structural purpose is to generate trust in the policies and people it wishes to have direct the state. For this reason we say it is qualified by a fiduciary leading function. Nevertheless, a political party may violate the trust people place in it, and may even guide the state into violating its own structural purpose of justice (think of the Nazi party). Nevertheless, the norms do not go away and they cannot be ignored. It is a common saying that even criminal organizations have their own internal ethical rules to which they adhere, so that there is “honor among thieves.” And even the most violently anarchistic organization would quickly fall apart if it became devoid of all observance of norms of fairness or trust among its own members.

We are therefore in agreement with the part of the objectivist position which holds that norms are real and cannot be ignored even if we try. In other ways, however, we must disagree with the classical objectivist position. For instance, we cannot agree that norms are only extrapolations from the nature(s) of things, so that those natures make the norms possible. Our theory holds instead that there is a distinct law side to creation, the norms of which exist whether or not there are things of a particular type. This has seemed to some critics to be a minor point, so that they take our position to be another version of objectivism. But holding that laws and things exist in mutual correlation is not a minor point. For if norms were merely our summaries of the inviolate natures of things, it would be impossible for any thing to disobey those norms without violating its very nature and thus becoming something else.6 Thus our theory, unlike objectivism, can account for the fact that individual activities and communities can retain their identity while disobeying norms.

These points further support our position that norms must be regarded as a distinct side of reality, not identical with the things, acts, and communities they govern. And it is why we do not call the purpose of an act or community as it is normed by its leading function, its “objective” purpose. The normative purposes included in the leading functions of human acts and artifacts do not reside in the objects of our experience any more than they reside in us as experiencing subjects. This is why I called their leading functions “structural” purposes, referring to the cosmic law framework whose type laws determine the structural order of every created individual.

We also disagree with traditional objectivism’s position that human reason is autonomous and neutral in its reading of norms from the natures of things. This point is what makes the disagreements over them lead subjectivists to reject objectivism. For if norms are really “read” from the natures of things we experience by pure unbiased reason, they ask, why doesn’t everyone see them alike? By contrast, however, we deny that norms and normative structural purposes are interpreted in a neutral fashion. Instead, we contend that although all people have an intuitive recognition of norms in their pre-theoretical experience, those norms will always be interpreted (and misinterpreted) quite differently depending on the divinity belief which regulates their understanding. A pagan view of divinity requires a reductionist view of reality that overestimates any norms closely associated with the aspect(s) supposed to be divine, and correspondingly underestimates or denies the reality of those which are least compatible with its reductive view. So with respect to norms also, we maintain that their interpretation (and to some extent even their recognition) is regulated by a philosophical perspective which is in turn controlled by one or another divinity belief. In this way the law framework theory can account for the fact that plagues subjectivism, namely, the widespread recognition of certain norms across cultures and over millennia (think of the many ethical and justitial truths that have been recognized by every highly developed culture). And at the same time it can also account for the sharp disagreements over the interpretation of norms which is so problematic for objectivism.

Since it’s subjectivism that is in vogue right now, I’m going to aim an additional critical point its way in the form of a question. Why should we think that disagreements over norms show they’re really only subjective biases? Why is that conclusion drawn for norms and not for, say, colors? Two people can — and often do — look at the same object in the same light at the same time and still disagree on whether it is more green than blue, for example. But does this prove that colors are merely our subjective biases rather than real (passive) sensory qualities of things? Surely not. But, then, why draw that conclusion for norms?

In sum, the program of eliminating norms in order to deal with the pure facts is, we say, destructive of social theory and impossible in fact. What “ought” to be is always part of what “is.” Norms, like natural laws, have an existence distinct from both subject and object with God as their source; He alone is the law-giver to creation. This is why norms can and do continue to govern creation even when people exercise their freedom to disobey them. And it’s also why any theory that attempts to pare down human activities and communities to the “bare facts” by eliminating norms is attempting something which is self-defeating. To strip away their norm-governed structural purposes and ignore their leading functions is to destroy their specifically human and social character, and ends up rendering them incomprehensible.

12.3 INDIVIDUALISM VERSUS COLLECTIVISM

Another of the dominating problems of social theory is whether to take an individualist or a collectivist view of society. In fact, every writer on the subject has leaned toward one or the other horn of this dilemma for such a long time that it is now a commonplace assumption that no one can help but be one or the other, or try to combine them in different respects.

Individualists insist that the basic social unit is the individual person on the ground that individuals can exist without communities, while communities are formed by, and comprised of, individuals. The individualist, Thomas Hobbes, for instance, held that human life was originally completely “solitary,” with the formation of social communities coming later. The motive for forming them, he thought, was that a solitary life was also “poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” He did, however, believe that communities, once formed, were realities whose natures it is important to understand. Other individualists, however, go so far as to say that there are no such realities as social communities; all that really exist are individuals and the agreements they make to relate to one another in certain ways.

Collectivists, on the other hand, assert that some form of community is the basic social reality, since that is what produces and sustains individuals. They view the individual as literally a part of a larger social whole, without which the part could not exist at all. For example, Aristotle said:

Thus the state is by nature clearly prior to the family and the individual, since the whole is of necessity prior to the part. . . . The proof . . . is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficient. (Politics bk 1, ch 2)

Here, then, are two positions that each seem to have a good argument in their favor. The collectivist asks how there could be individuals if there were no parents and extended family group to care for mother and infant, while the individualist asks how there could be any group if there were no individuals to form it. This sounds a lot like the old joke about which came first, the chicken or the egg, and it might be funny were it not that this debate has very serious consequences for both social theory and practice. This is particularly so in connection with the understanding of justice with respect to the institutions and organizations of society, as we shall see in the next chapter.

Before we address the individualism/collectivism dilemma, however, let’s dispose of the question of whether social communities are to be considered real at all. Even though we do not usually speak of a social institution or organization as a “thing,” that does not mean it isn’t real; we don’t usually speak of a person as a “thing” either, but that doesn’t mean people are not real. And surely social communities are recognizable as distinct unities, just as things and people are. Besides, the argument that there are no real social institutions but only individuals and their relations is self-contradictory. If it’s granted that inter-individual relationships are real, then how can it be denied that marriages, families, businesses, churches, schools, labor unions, political parties, etc., are also real? If the relations between individuals are real, then so are the communities constituted by them. Besides, the view that they are something over and above the individuals who are their members is supported by the fact that for all social communities except marriage, their identity persists even when their members change. In addition, we have seen that social communities function in all the aspects of experience and have differing qualifying functions determining their natures. So in all these respects they are the same as the other artifacts humans form and should be regarded as just as real as they are.

But that extreme version aside, the heart of every individualist theory is the claim that individuals are more basic realities than communities. The sense of “basic” intended is the same as that which occurred in reductionist theories of reality. It means that individuals can exist without communities but communities cannot exist without individuals. This, however, is an extremely implausible claim. As Aristotle pointed out, a solitary individual will quickly die. Perhaps the easiest way to see the truth of this point is to think of the extended period of time that human infants are utterly helpless and require constant care and attention. Not only that, but immediately after giving birth a nursing mother also would need protection and provision of food so that without some social arrangement neither could survive. And although we may be tempted to imagine that an isolated adult could survive in the wild, that would only be possible because of the knowledge and skills such a person would have already acquired by having been raised in human society. Finally, there is no evidence that there ever was a time when people lived in complete isolation without any social community whatever as Hobbes claimed, or without any ruling authority as was claimed by another famous individualist, John Locke. So far as we know, people have always lived in families, tribes, clans, or villages, and with some sort of recognized authority, rules, and traditions.

On the other hand, the collectivist position sees every person as dependent upon, and therefore literally a part of, some all-inclusive social whole. That, however, is completely at odds with the nature of social communities. A social community is not self-sufficient in relation to individuals, since it cannot exist without individuals any more than individuals can exist without it. So our first objection to collectivism attacks its most fundamental claim just as our first objection to individualism attacked its most fundamental claim. Both theories are wrong, we say, because individuals and social communities exist in a mutual correlation in which neither can exist without the other: neither is “basic” to the other because neither was ever the source of the other, as both were created simultaneously by God.

Moreover, from the theistic point of view, it is abhorrent to regard individuals merely as parts of any human social community. They are not merely “cogs in the machinery” of the state, or “cells in the organism” of the human family. The most uniquely human thing about people, from the theistic standpoint, is their capacity for fellowship with God. This was the very purpose for their creation, according to Genesis, and it is this which makes it possible for humans to be members of the spiritual kingdom of God which transcends every humanly formed community. This is so pervasively true of humans that even when they reject the true God they cannot help but believe in something else as divine. When that happens, they thereby become members of a corresponding spiritual kingdom of false belief, which also transcends every humanly formed community. For this reason, we must insist that although humans always live and function in social communities, there is no humanly formed community of which they are nothing more than parts.

Here, then, we have additional reasons why pursuing our non-reductionist program for theories, and combining it with the specific teachings of scripture just mentioned, leads to the position that although humans function actively in all aspects of creation human nature is not merely the sum of those functions. As we noticed in chapters 9 and 11, and earlier in this chapter, human nature is more than all these functions since it resides in the human “heart,” or self, which has a unique relation to the creator who transcends creation. Therefore, unlike all other creatures, humans have no single qualifying function. Even their function in the fiduciary aspect, which expresses their faith, is not identical with their heart’s relation to God. Rather, it is the heart’s orientation with respect to God (or whatever it embraces as divine in His place) which directs the exercise of every act of faith. Properly oriented, the heart’s relation to God thus extends beyond created reality to the uncreated Creator and, as was already pointed out, it is that relation which most centrally characterizes humans as religious beings. At the same time this is perfectly compatible with the fact that humans — individually and collectively — both perform acts and take part in social communities which do indeed have qualifying functions.

We have also already seen why social communities, by contrast, cannot have the sort of direct relation to God that each human can have. They are, to be sure, dominated by norms, ideas, traditions, etc., which serve God or some God substitute. But even religious institutions cannot have an eternal destiny as persons do. Thus, there is a crucial difference between the nature of any social community and human nature which forbids our construing a person as nothing more than a part of some social whole.

For the same reasons, we must also reject the major consequences of each of these traditional theories. For example, individualist theories regard all social communities as formed by the voluntary association of free individuals who have contracted among themselves to promote some value they hold dear. As a consequence, these theories usually assume that such “social contracts” are the best way to protect the worth and welfare of the individual as being of prime importance. They thus regard the welfare of the larger community as secondary. Collectivist theories, by contrast, argue that individuals are always dependent on social communities, both biologically and culturally. On their view, social communities are not at all freely invented by people who once did without them and could still do without them if they wished. This usually results in their estimating the worth and welfare of the all-encompassing social community as not only more important than that of any one individual, but also as more important than all the sub-communities contained within it. In this way each theory’s answers to the question about whether the individual creates the community or the community creates the individual generate important differences in social priorities. In case of conflict between the good of the social whole and the good of the individual, one theory gives priority to the individual while the other gives priority to the community. Unlike our theory, neither side can strike a principled balance between the individual and society because each has started by assigning a reductionistic primacy to one or the other.

This controversy over where the social priority is to be placed does not merely result in vague differences in the attitudes of those on each side. It is not simply that in a court case a judge holding the individualist view would tend to lean toward favoring the rights of the individual, while a judge who is a collectivist would tend to lean toward favoring the welfare of society. Such results, all by themselves, would be important enough and result in significant differences in the way cases are decided. The true significance of the two positions is even greater, however, in that each position gives a particular slant to the very idea of justice which underlies not just judicial judgments but the way laws are written.

To appreciate the extent to which this is so, consider that the collectivist views of Aristotle and Marx defined justice as the maintenance of harmony among the parts of a society for the preservation of society as a whole. In their view this meant that every social community other than the state should be totally regulated by the state for the benefit of the state. They took this position because all other communities were supposed to be parts of the state, which was seen as the all-encompassing social whole. Justice is thereby held to be whatever tends to preserve the state in the opinion of the state. This view therefore sees no intrinsic limits upon what the state may demand or forbid. Consequently it sees human rights as nothing more than whatever freedoms it is in the state’s interest to grant. By contrast, the influential individualist theory of Locke held that the core idea of justice is the protection of the life and property of each individual. It views individuals as the possessors of “natural” moral and legal rights which the state does not give and which it was formed to preserve. The only way any natural rights may be justly lost, Locke thought, is if individuals voluntarily agree to surrender them to the state. Locke’s view is a big improvement over the collectivist view, for sure. (And there are other parts of it that derive from scriptural teachings, with which we have no dispute.) But his individualism leads him to restrict the idea of justice to the protection of individual lives and private property, so that there is no room left in his theory for state concern with public justice where private property is not involved. On that score, Locke’s account of government makes it sound more like a private security company than the ruling body in the state.

I will not pursue the consequences of these two traditional positions any further right here since they will be criticized in greater detail in the next chapter. For now it is enough to point out how each of the traditional views skews the meaning of justice by defining it as either more fundamentally the preservation of individuals or of the collective whole of society. On the other hand, our law framework theory will deliver us from having to choose between individualism and collectivism. It points out that since the norms of justice which are the source of human rights reside neither in individual persons nor in the collective whole of society, neither is to be favored over the other in the administration of justice. Instead of narrowly focusing on one or the other, the law framework theory provides a wide-angle lens to take in the entire spectrum of life so the norm of justice can be equally applied to both individuals and social communities.

12.4 PARTS AND WHOLES

In dealing with the collectivist position, we briefly noticed that Aristotle defended it with the argument that a whole is basic to (his term was “prior to”) any of its parts. He made this point in reference to the relation of individuals to the state — a point the theistic view of humans vehemently denies. But there still remains the question of whether certain social communities are actually parts of others. This question is important because all social theories accept the idea that since a part is dependent on the whole, any community which is part of another is therefore subordinate to that other. Thus any communities which are parts of another are to be ranked lower in authority, and the community comprising the whole is given supreme authority to regulate all the communities which are its parts. So is there a supreme social authority? And if so, what is it? These questions need to be answered by any theory of society whether it works from a collectivist, individualist, or law framework point of view.

I stress the importance of these questions for any social theory, because they have generally been associated more with collectivist theories since those have always been specific about which single institution they regard as the overarching community that encompasses all individuals and all other communities as its parts. This is because it is the all-encompassing character of their favored institution they see as justifying the claim that it should have supreme authority in human social life. Individualist theories, on the other hand, have a reputation for resisting any all-encompassing social authority. Because they regard individuals as creators of communities rather than vice versa, individualists usually claim that people have rights which exempt them in certain ways from the authority of any community.7 But merely exempting individuals from certain sorts of authority will never, by itself, prevent at least some communities from being subsumed as parts of another. So while most individualist theories have exempted individuals from community authority in certain respects, they still ended up subsuming all other communities under some one supreme community supposed to encompass and rule all the others. So our questions are, indeed, unavoidable for every social theory alike: how may we tell if one community really is or is not a part of another? How can we know when we are confronted with a genuine part-whole relation and when we are not?

In keeping with our law framework theory, we may now appeal to the idea of each thing’s qualifying function, along with the networking of aspectual and type laws, to answer this question. For it appears that the law framework theory can provide new insight for determining under what conditions a genuine part-whole relationship exists. It does this by allowing us to make some important distinctions which show that many relations often spoken of as part-whole relations are really not.

We will start by accepting the view defended by Aristotle that a part cannot exist separately from the whole of which it is a part. The sort of independence he denies to parts includes two elements, namely, that a part must participate in the internal organization and functioning of a whole, and that it either cannot come into existence or cannot function separately from the whole. Of course, neither of these two conditions taken by itself is sufficient to identify a genuine part-whole relation. The fact that X is unable to exist or function apart from Y will not make thing X part of Y, since there are whole-whole relations in which one or both cannot exist without the other. For instance, a tree is an individual whole having its own internal parts, but it cannot come into existence or function separated from the earth. It is not, however, part of the earth. Likewise, X’s functioning in the internal organization of Y will not necessarily make X a part of Y. A small stone can function in a bird’s digestive tract to help grind its food, but is still not part of the bird. But while neither of these conditions alone can identify a genuine part-whole relation, traditionally it has been held that the combination of the two is sufficient to do the job.

We must disagree. We have now seen that although humans cannot exist apart from some community, and although they do function in the internal organization of communities, nevertheless they may not be regarded as mere parts of any community. Humans are therefore a decisive counterexample to the traditional view. What needs to be added to the traditional conditions is that a thing must also share the same qualifying function with any larger whole if it is genuinely to be a part of that whole. Thus the new criteria necessary for sorting out genuine part-whole relations is that something must: 1) function in the internal organization of a whole, 2) be unable to come into existence or function apart from the whole, and 3) must have the same qualifying function as the whole, in order to be truly a part of that whole.

This shows us that in ordinary speech we often call one thing a part of another only because it satisfies condition two by playing a role in its internal organization or functioning. For instance, it is ordinary speech to say that a large rock in the corner of the yard is a part of the garden. But even the traditional part-whole theory would have had to reject the rock as genuinely a part of the garden since the rock can exist independently of it. Our new concept agrees with that judgment, but gives the additional reason that the rock is physically qualified while the garden is aesthetically qualified. It is still true that the rock is included in the garden, of course, but it is included as a whole within a greater whole, rather than as a part of a greater whole. The same is true of the plants in the garden which are also not to be considered parts of it; the plants are biotically qualified natural things, while the garden is an aesthetically qualified artifact.

This leads us to draw yet another new distinction, namely, that whenever one thing functions within another larger whole but fails any of the three criteria for being a part of that other, we will call it a sub-whole rather than a part of the other. And we will speak of the greater wholes which include sub-wholes as “encapsulating” them, and so call the greater wholes “capsulate wholes”. These terms are intended to convey the notion of wholes included in a larger container-whole, or capsule, without actually being parts of the container. And we will now speak of the relation of the sub-wholes to their capsulate whole as “capsulate” relations to distinguish them from part-whole relations.8

This part of our theory yields results that go beyond what is possible relative to the traditional part-whole theory. To illustrate this, take the example of a (non-social) artifact such as a marble sculpture of a human body. An important part of our explanation of the nature of the sculpture will be explained by its foundational function (the historical qualification of the process of its formation), and by its leading function (the aesthetical qualification of the plan guiding its formation). But if the question is asked as to how we are to understand the relation of the marble to the work of art as a whole, it would be impossible to answer in terms of part to whole. Even on the traditional view, the marble can’t be a part of the sculpture since it can exist without it. And on our criteria the marble also has a different (physical) aspectual qualification from the work as a whole. Besides, it doesn’t make much sense to speak of the marble as functioning in the internal organization of the sculpture! But our idea of capsulate relations can do much better. According to it, we can say that the marble, as the natural material of the sculpture, is not a part of the work of art but is a sub-whole included within a capsulate whole. This allows us to explain the distinctly new whole produced by carving the marble, without having to say either that the marble is part of the sculpture (when its parts are obviously its head, arms, legs, torso, etc.), or that no new whole has been formed and that it is essentially still just a piece of marble (as Aristotle was forced to say).9

Moreover, the relation of the piece of encapsulated marble to the whole sculpture shows another characteristic that is typical between sub-wholes and their encapsulate whole: no amount of knowledge of the nature of the subwholes existing within an encapsulate whole can ever yield knowledge of the nature of the capsulate whole. This is precisely because they have different natures owing to the fact that their qualifying functions are different. In this instance it means that knowing all the physics there is to know about marble will never yield any information about the sculpture as a work of art.

The distinction between part-whole and capsulate relations also applies to natural things as well as artifacts, and considering a few examples of this may help make the difference between them clearer. Take, for instance, the relation of the atoms in a plant to the plant as a whole. The atoms surely function in the internal organization of the plant. But since atoms of every chemical element existed before life ever arose on earth, and since atoms are not destroyed when the plant is, there is no question as to whether atoms can exist separately from the plant. Moreover, atoms have only a physical qualifying function while the plant exceeds the physical by having a biological qualifying function. The atoms are not, therefore, parts of the plant but stand in the relation of being sub-wholes to a capsulate whole. By contrast, the relation of the plant’s cells to the plant as a whole is a part-whole relation. The cells function in the internal organization of the plant, they can’t come into being or continue to function (for long) apart from the plant, and they do have the same (biological) qualifying function as the plant.

The relation of atoms to a molecule, however, would be a capsulate relation. For example, atoms of hydrogen and oxygen can’t be parts of the molecule H20, even though they function in its internal organization and have the same physical qualifying function. This is because they can exist and function independently of their being combined in it. So this is yet another case of a capsulate relation. And as with other capsulate relations, the properties of the whole cannot be deduced from those of its sub-wholes.

In every case we can think of, sub-wholes that are bound together in a capsulate whole retain their own identity since, considered apart from their encapsulation, their qualifying function remains the same. But when they are included in a capsulate whole, their own qualifying functions are overridden by that of the capsulate whole. That is, the sub-wholes exist and function within a whole which has properties and a leading function which none of them possesses singly but which each now serves. For this reason (and other reasons), subwholes cannot be considered to be causes of the capsulate wholes in which they are bound. They are necessary conditions for such wholes, but are not also sufficient conditions for them. The additional factor needed to account for capsulate wholes is, we say, that they are made possible by a second sort of type law. So in addition to postulating type laws that range across aspects to determine how properties of different aspects may be combined in individual things comprised of parts, we also postulate type laws to account for how there can be wholes comprised of sub-wholes having either the same or a different qualification.

This contribution to the understanding of part/whole relations as distinct from whole/sub-whole relations can now be applied to social communities. One social community will be part of another if and only if it cannot come into existence or function without the other, it functions in the internal organization of the other, and has the same leading function as the other. Otherwise, no matter how much one community may be under the influence (or even the complete control) of another, it is not part of it. Likewise, one community is a sub-whole encapsulated within another when (1) it functions in the internal organization of the other and (2) lacks the qualification possessed by the larger whole, even though (3) it could exist apart from the larger whole.

When these definitions are applied to various social communities, the results are very important. For our criteria show that while there are cases in which one community is actually part of another, the major types of social institutions and organizations cannot be parts of one another. A corporation, for example, may have within it separately organized divisions or subsidiary companies, which are actually parts of it. And a state may have parts such as provinces, shires, departments, counties, townships, districts, boroughs, and municipalities. A national army and courts are also parts of the state. But a business can never be a part of a state. The two have different leading functions, and therefore different natures and structural purposes. Moreover, their internal organizing principle (type law) is also different, so that they are irre-ducibly different types of social communities.

The same holds true of the relation of a family to a state. A family has a distinct (ethical) leading function and is structured by a distinct type law. It can exist and function where there is no state. Thus, even when it exists within the territory governed by a particular state, a family can never be one of that state’s parts. A proof of this is that each member of a family may at the same time be a citizen of a different state, which would be impossible if the family was part of the state. Similarly, a church, synagogue, or mosque can never be part of a state or of a business, or of a family, any more than any of them can be parts of a religious institution. All these institutions and organizations stand in whole-whole relations to one another, not part-whole relations.

But not only are the major institutions and organizations of society not parts of any one institution, neither are they encapsulated sub-wholes in any one overarching community. What could that capsulate whole be? The most oft-nominated candidate is the state, but if the state were really all-inclusive each of the encapsulated sub-wholes would then have its leading function overridden by the state’s justitial leading function. This means the encapsulated communities would cease to function in the different ways that correspond to their distinctive structural purposes. Instead they would all be absorbed into the purpose of legislating and enforcing public justice, and there would be no communities left to accomplish the purposes of earning a living, producing art, educating the next generation, or expressing faith. The point is simple but crucial: either we have distinct communities or we do not, and no community can retain its distinct structural purpose while at the same time functioning as a sub-whole within another all-encompassing community. For this reason we see the ideas of a state business, or a state church, or a state school to be just as incoherent as the idea of a state family. To the extent that an organization or institution is a church, a school, or a business, it is precisely not a state and vice versa. Of course, a state may choose to support another community such as a school, just as a church, labor union, foundation, business, or family may support a school. But in every case that support should be afforded in the recognition that a school has a distinct nature from the communities supporting it, so that its own internal authority should not be assimilated to that of any supporting organization.

12.5 SPHERE SOVEREIGNTY

These results of our law framework theory therefore lead us to reject any hierarchical view of society as a whole. There are, inevitably, hierarchies within communities; but we reject every notion of a “global” hierarchy encompassing the whole of society.10 This is so whether the hierarchy is thought of as having many levels or is simply the difference between the all-encompassing supreme institution and the communities it supposedly subsumes. Since the distinctive natures of social communities show how seldom one can be a part or sub-whole of another, we are led to a structurally pluralistic view of society. This pluralism echoes within the social aspect the same sort of irreducible pluralism that holds between aspects in our theory of reality: just as no aspect is more real than or the source of any other, so too there are irreducible “spheres” of social life none of which is more real than or the source of any other. Hence we also view the different sorts of authority found in the various communities as irreducible and complimentary, rather than as derived from one all-encompassing source. Therefore, on this view there is no institution which can rightfully claim to have supreme authority for the whole of human life. Instead, each type of community is seen as having not only a distinctive structural purpose determined by its leading function, and a distinctive internal organization set by its type law, but also its own distinct sort of authority. That means each should enjoy a sovereignty in its own social sphere that guarantees it freedom from interference by other communities so far as its internal operations are concerned, so that each should be free to make its own rules of operation in deciding how best to fulfill its structural purpose. This is the principle Abraham Kuyper elaborated around the turn of the last century, the principle he called “sphere sovereignty.”11

It is significant for the Christian-theistic character of this principle that Kuyper derived his formulation of it not from a theory of reality, but from scripture. He noticed that the New Testament not only teaches that all authority on earth derives from God, but that it also recognizes multiple authorities on earth rather than one supreme authority. The Hebrew scriptures already suggested this by the way the prophets of Israel viewed the authority of their king as limited rather than total. But this point comes across even more strongly when the New Testament speaks of parents as authorities in a family, government officials as authorities in the state, and clergy as authorities in the Church. In developing this line of thought, Kuyper was continuing a tradition that had taken its impetus from the thought of Calvin who had long before commented on the different callings of life and the limited authorities proper to each:

And that no one may presume to overstep his proper limits [of authority], [God] has distinguished the different modes of life by the name of callings. Every man’s mode of life, therefore, is a kind of station assigned him by the Lord. . . . [hence] The magistrate will. . . perform his office, and the father of a family confine himself to his proper sphere . . . and in following your proper calling no work will be so mean and sordid as not to have splendor in the eye of God. (Institutes, III, x, 6)

The social principle of sphere sovereignty is thus another instance of our theory being guided not only by a non-reductionist view of reality as required by theism, but also by specific scriptural teachings that reach their clearest statement in the New Testament.

It should be emphasized right away, however, that this principle is not merely negative. It does not mean only that there are external limits to the authority of each distinctive community which therefore set a “wall of separation” between their spheres of authority. Since the negative limits themselves are set by the internal nature of each community, the principle also has the positive aim of allowing each to fulfill its distinctive structural purpose. Neither is sphere sovereignty simply a practical piece of advice that says: unless the distinctive character and purposes of communities are recognized, there will be strife between them in any given society. Nor is it a matter of allowing each a niche of non-interference because, say, business or art has often been found to flourish when that is done. Rather, the sphere limitations of the authority of each type of community are set by the nature of its type, so that over-stepping those limits always proves harmful to the community that over-steps as well as to the other communities it infringes upon.

The idea of sphere sovereignty will now serve as the guiding principle for our general overview of how all the various communities of society should relate to one another. At every turn, our theory will seek to reflect the belief that there are mutually irreducible, and yet inseparable, spheres of social life. The various communities that correspond to these spheres will likewise be seen as both mutually irreducible and inseparable, because they arise out of diverse human needs, abilities, and concerns which are qualified by diverse aspects. For example, we all have concerns about our physical safety, our biotic necessities such as food and shelter, and about our sensory perception of the world around us including our avoidance of pain and the enjoyment of pleasure. Often the sciences studying these aspects, which were lower on our list, are called “natural sciences” while the sciences investigating the aspects higher on our list, such as sociology and economics, are called “social sciences.” But it is important to notice that the aspectually different concerns studied by the social sciences are all also “natural”; that is, although the ways we respond to these concerns are under our formative control, the concerns themselves reflect the ways human nature was created by God rather than ways that were wholesale invented by us.

For example, because of the order of creation all humans inevitably have a natural interest in social matters (in the narrower sense of “social”) which results in the development of styles of dress, levels of social status, customs of politeness, etc. They also have economic concerns centered on the making of a living, and all express their aesthetical needs or abilities by the creation or enjoyment of art and sport. Likewise, all people are concerned with justice, love, the education of their children, and the exercise of their faith. It is our contention that since these aspects of life are natural, no people can entirely suppress them. Rather, they are so pervasive and important to human life that people inevitably form communities to promote and protect them.12 At the same time, however, it should be clear that the spheres of social sovereignty I’m speaking of do not correspond to different groups of people. No one can fail to be concerned with any sphere, whether they are members of a community devoted to its interest or not. And the same people who are members of one such community (say, a state) are usually also be members of others: e.g., employees of a business, members of a synagogue, church, or mosque, participants in a political party, students of a school, etc.

In order to make clearer the social overview provided by our principle of sphere sovereignty, let’s return to the idea of authority in society and apply the principle to it. This focus will allow us to see how the sphere sovereignty principle answers the questions: by what authority does one person (or group of them) make laws that tell others what they can and can’t do, and where does such authority come from?

There have been many answers given to these questions. One of the most influential answers was Aristotle’s theory that the nature of authority lies in rationality and virtue. Those who have the most intelligence and are ethically virtuous should therefore rule the rest. Another enormously influential answer, proposed by Marx, is that the authority to rule resides in economic ownership. This means that those who have the wealth and own the means of producing the necessities of life not only inevitably will, but should rule the state which should in turn rule all other communities (until the communist society comes into existence). Yet another view is that of monarchy, which holds that authority is biologically inherited. On this view, a person rightfully tells others what to do because that person is the nearest of kin to the last person to have that authority. Still another theory is that it is military power which is identical with authority, so that might makes right. Still other theories follow Rousseau by vesting authority in people’s wills, giving either the will of the majority or the “general will” the right to rule.

In all these theories the nature of authority is identified with some particular human function: reasoning, making moral judgments, producing goods and services, reproducing, exerting military force, or acts of volition. Each of these is therefore an answer to the question of the nature of authority, and each identifies that nature with a particular aspect of humans or with the human will. Thus they claim that authority is fundamentally of a rational, or moral, or economic, or biological, or volitional character. Once this is done, however, the issue of the source of authority is also decided. In each case it will be the people who excel in the particular function of human nature which is the source of authority who should therefore exercise it over the whole of human life. For example, suppose the basic nature of all authority whatever is thought to reside in the will of the majority. In that case there may still be other kinds of authorities in society such as the authority of parents in a family, or of a teacher in a school, or of the owner of a business. But ultimately these others will exist only because the majority will allows them. They must be viewed as subsidiary authorities derived from the fundamental authority.

In the theories of the past, whatever community was supposed to have the kind of authority which is basic to all other kinds of authority was seen as the community which includes the others as its parts. In the history of Western culture the state has most often been the institution accorded that status both in theory and in practice — and this is still true. But no matter which community is assigned this role by a theory, the view of authority it presupposes is reductionist, and the view of society which results is hierarchical and literally totalitarian. For any community supposed to be the source of all authority is thereby taken to have all other social communities under its authority in all of their aspects, and so to be supreme over the totality of human life.

Even individualist theories cannot avoid this totalitarian result once they accept the nature of all authority as residing in a particular human function and consequently in a particular institution. For if the authority of all other communities is regarded as derivative from some particular one that is taken to be the supreme authority, the other communities cannot help being viewed as parts or sub-wholes of that supreme community. As we already saw, individualist theories try to avoid totalitarianism by finding some respects in which individuals are exempted from the authority of the supreme institution. But once a particular community is regarded as embodying an authority that is basic to all other kinds, such exemptions become not only hard to find in theory but impossible to obtain in practice.

The classic statement of the theory that the state is the community with the supreme all-encompassing authority is found in Aristotle’s Politics:

Every state is a community of some kind, and every community is established with a view to some good; for mankind always act in order to obtain that which they think good. But, if all communities aim at some good, the state or political community, which is the highest of all, and which embraces all the rest, aims at good in a greater degree than any other, and at the highest good. (Politics bk. 1, ch. 1)

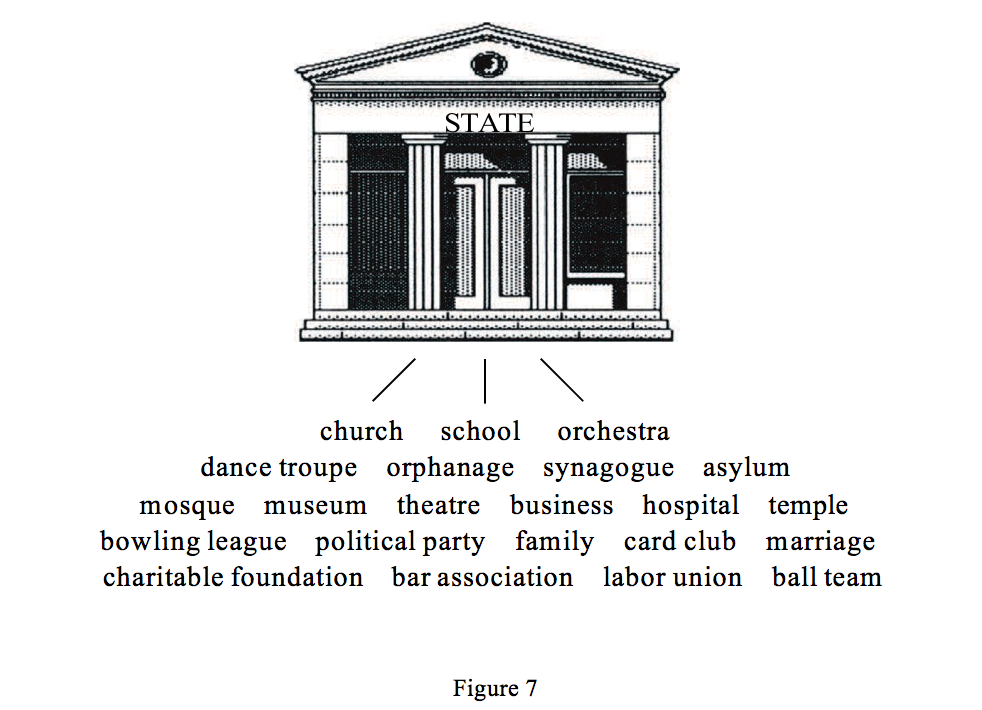

The schematic drawing in Figure 7 may help represent the hierarchical, and thus totalitarian, overview of society expressed by the quote, as it applies to modern society.

It has already been pointed out how viewing all authority as derived from God opposes every totalitarian theory of society. And we saw that scripture explicitly supports the idea that there are a multiplicity of authorities such as parents in a family, the owner in a business, the ruling powers in the state, and the clergy in a religious institution. We drew the implication from this that no single kind of authority is the only kind, the source of all other kinds, or supreme over the other kinds. But there is another important consequence to be drawn as well, namely, that it can never be right to defy a legitimate authority since it has its origin from God, not humans. No individual or group, including the will of the majority, is the source or creator of authority. Humans don’t create authority, they bear it. So while vote of the majority may indeed be the best way to select those who are to bear authority in the state, voting does not create the authority the elected come to bear. On the Christian theistic view, then, we may regard bearers of an authority as unworthy and seek to replace them with other authority-bearers. (Authority-bearers in the state may be impeached or recalled, for example, or the state may have to remove children from abusive parents.) But the authority itself can never rightfully be disrespected.